Libya's parliament ejects 'failed' prime minister

Loading...

| Tripoli, Libya; and Tunis, Tunisia

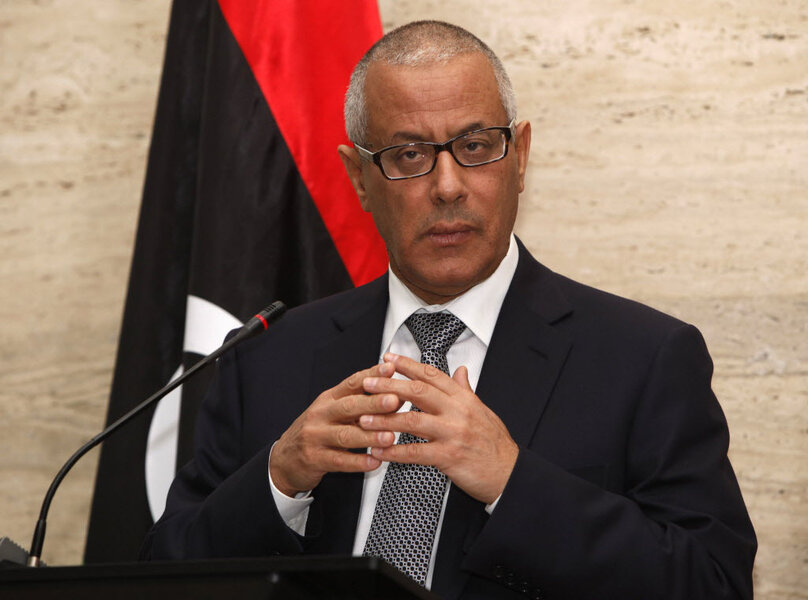

Ali Zeidan has been criticized, opposed, and even briefly kidnapped since taking office as interim prime minister in October 2012. Today he was removed from the job with a no-confidence vote by legislators who blame him for the country’s security and economic woes.

Defense Minister Abdullah al Thinni will become interim prime minister after a majority of roughly 180 lawmakers voted against Mr. Zeidan, the Associated Press reported.

Libya’s many militias operate with impunity, as demonstrated by an ongoing tussle over oil exports from eastern ports. Libyans seethe at stagnant public services and high unemployment. And while Zeidan isn't to blame for all Libya's woes, he has become a focus of criticism.

"Mr. Zeidan is a failure,” says Said Khattaly, a General National Congress member and chairman of its foreign affairs committee. “We have no army, no police force; people would like stability, freedom, and to be in peace.”

Zeidan assumed office as a compromise choice by the GNC after it rejected his short-lived predecessor, Mustafa Abu-Shagur, in October 2012. He boasted impressive credentials. Formerly a diplomat under former leader Muammar Qaddafi, he defected in 1980 and fled to Geneva, where he remained a voice of opposition for the next three decades.

Nevertheless, GNC members have attempted to mount no-confidence votes against him several times since last year, accusing him of poor leadership. Last October he was kidnapped and held for several hours, apparently by disgruntled militiamen.

The GNC has its own share of troubles. In early 2013, militiamen parked outside government ministries to pressure the body into passing a law barring public officials who served under Mr. Qaddafi from politics. Violent protesters barged into party meetings and assaulted lawmakers several times, most recently on March 2.

Many Libyans also accuse the GNC of wasting time. Lawmakers argued for months over whether a constitutional drafting committee should be appointed or elected. When elections took place on Feb. 20, most Libyans stayed away from the polls to express their frustration with politicians.

Oil output falls

Meanwhile, militiamen in Libya’s east have shut down oil ports there since last summer in a blow to Tripoli that has reduced Libya’s oil output to less than a third of capacity. Militia leader Ibrahim Jadhran is demanding more autonomy and oil revenues for the region.

Today a North Korean flagged ship that took aboard oil from Mr. Jadhran over the weekend evaded a Libyan naval blockade, reported the BBC. That may have helped spur today’s GNC vote against him. Still, legislators had been preparing since last week to vote him out, according to Mr. Khattaly.

Divisions between Libya’s executive branch and its legislators was on display for Western, Arab, and UN diplomats who gathered in Rome last week to meet with Libyan leaders.

Two Libyan delegations turned up, according to Karim Mezran, a resident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East who attended the Rome meeting: one from the GNC, and one led by Zeidan. The meeting was intended as a forum for explaining where assistance is needed most, Mr. Mezran wrote on the Atlantic Council’s website.

“Instead, the international community received a range of asks as expressed by [GNC President Nuri] Abu Sahmain and Zidan, who each delivered remarks, citing priorities that highlighted the growing chasm between the camps,” he wrote.