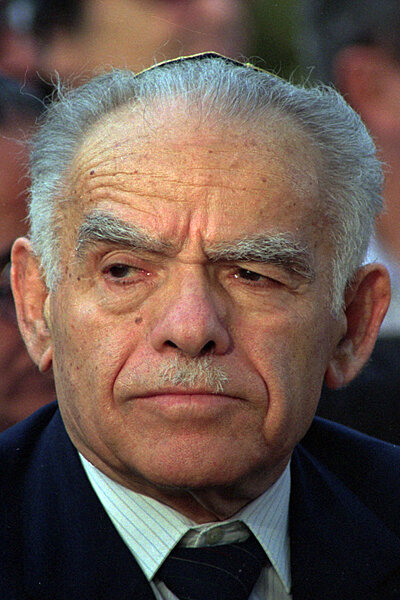

Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, an émigré from Poland whose parents had died in the Holocaust, was intent on bringing as many new immigrants to Israel as possible. When the Ethiopian government collapsed in 1991, he had 14,000 Ethiopian Jews airlifted to Israel. And he convinced the US to stop accepting Soviet Jews as refugees, funneling more than 1 million Soviet Jews to Israel instead.

But all of this cost money. During the end of President George H.W. Bush’s term, Mr. Shamir sought loan guarantees of $10 billion from the US to help cover the resettlement costs, which included building new homes and roads, finding jobs, and providing services for the new immigrants. (The mechanism was akin to co-signing a mortgage, in which a wealthier party with better credit can help a party with more modest funds to secure lower interest rates.)

The Bush administration was concerned, however, that the funding would be used to build new settlements that could jeopardize peacemaking between Israelis and Palestinians.

In the end, Shamir – a staunch believer that the West Bank and Gaza rightfully belonged to the Jews – never accepted Bush’s terms to freeze settlement expansion in exchange for the loan guarantees. But in 1992, when Yitzhak Rabin replaced him, Bush agreed to the full $10 billion in loan guarantees in exchange for only limited curtailment of settlement building – perhaps because he viewed Rabin’s centrist government as more supportive of America’s peacemaking efforts in the region.

The following year, Rabin signed the 1993 Oslo Accords with Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat.