As troop drawdown nears, is NATO surge working in Afghanistan?

Loading...

| Washington; and Kandahar, Afghanistan

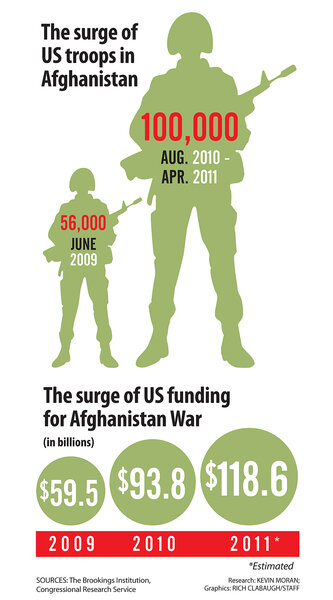

As the longest war in American history nears its second decade, US military power is at its zenith in the Afghanistan war. The surge of 30,000 new American troops into the most violent areas of the country, authorized by President Obama after a wrenching policy debate with his closest advisers in 2009, was designed to bolster overall NATO strategy to wrest momentum away from insurgents who were gaining territory and tacit support among locals eager for some peace and stability.

Now, however, the Pentagon will begin to fulfill a promise made by Mr. Obama to start drawing down US troop levels in July 2011, marking the first tangible step toward an exit from the conflict.

Against this backdrop, as the president's advisers decide precisely how many troops to bring home this summer, they will be grappling with a key question: Has the surge worked?

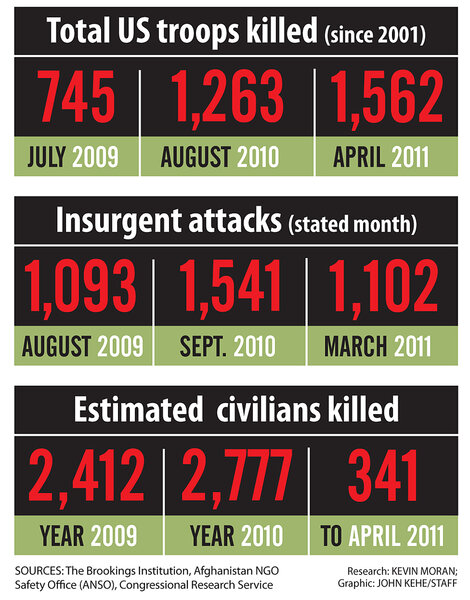

To this, the US military tends to give a qualified answer: not quite yet. Spectacular attacks by insurgents continue throughout the country. Roadside bombings are up, as is violence in many parts of the country, officials acknowledge. And more NATO soldiers died during this April and May – the opening months of the fighting season – than in that same period of any year of the war.

The same officials are quick to add, however, that the surge is having an impact in some pivotal areas. Commanders have stepped up Special Operations Force attacks on insurgent leaders to considerable effect. And America's exit strategy – to train Afghan security forces so that they can keep the peace when US troops leave – is continuing apace.

What's more, it makes sense that violence is on the rise, they argue: NATO troops are in areas where they have never been before, and insurgents are fighting back. "We're seeing the Taliban come back, not unexpectedly, to try to retake territory we took last year," Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Adm. Mike Mullen told reporters on June 2.

The common denominator in these assessments is that the military needs more time: The new troops technically have not been in place for long, commanders universally point out – it was only in the fall of 2010 that the bulk of forces arrived in the country.

The White House is still awaiting recommendations about troop withdrawals from Gen. David Petraeus, the top US commander in Afghanistan. But at the Pentagon's urging, the number of troops who will actually return to the United States is expected to be relatively modest – somewhere in the neighborhood of 10 to 15 percent of US surge forces.

Yet defense officials are aware, too, that the country's patience for war is limited, particularly as Congress expresses growing concern about the cost of the war – some $5.3 billion a month in Afghanistan – in the midst of an economic crisis. Mullen acknowledged that money matters will probably affect the upcoming debate over troop withdrawals in Afghanistan.

"There is not a decision in government where cost is not front and center, including Afghanistan," he told reporters.

US officials are not the only ones in danger of losing patience.

While the Pentagon cites a quarterly survey of 10,000 Afghans that found in March roughly 40 percent feel that security is "good," this is a 10 percent decline from December survey levels.

"Where the surge forces have initially been put to use they have been successful," says Jeffrey Dressler, an analyst at the Institute for the Study of War in Washington. "But there are other aspects that are critical to whether we can say whether the whole thing was a success or not."

This includes security lapses, shakedowns, and lack of services. To address some of these points, the civilian surge was an integral component of Obama's strategy for Afghanistan. Along with the troop influx, the White House promised government experts, too, to help with agriculture, court systems, and corruption.

But the civilian surge has largely failed to materialize, many US officials say.

Many civilian experts have been hired to fill lucrative US government jobs in fields like "strategic communications," advising the military on how to craft their message both back home and for locals. Civilians have for the most part stayed concentrated in Kabul, rather than in the provinces that are less developed and more dangerous.

"The civilian surge didn't show up," says Norine MacDonald, president of the International Council on Security and Development, a foreign policy think tank with an office in Lashkar Gah, Afghanistan. "The troop surge just has not been accompanied by the promised corresponding development and civilian surges."

The gains that have been made on the battlefield "are being undermined" by a lack of similar efforts in the fields of aid, development, governance, and counternarcotics, Ms. MacDonald adds.

What's more, while troops have pushed back the Taliban in formerly violent areas of the south, it remains an open question whether the Afghan security forces will be able to hold on to security gains.

Even as the ranks of Afghan soldiers and police grow, a congressionally mandated report released by the Pentagon in April concluded that "if the levels of attrition [within the Afghan National Army] seen throughout the past five months continue, there is a significant risk to projected ANA growth." NATO commanders say they still need more trainers to work with the Afghan Army. Among the core causes of attrition, the study found, are "poor leadership and accountability."

At the same time, one of the most promising developments of the past year has been a bottom-up strategy in parts of the south that emphasizes accountability – including the development of local security forces vetted by village elders. The expansion of local security programs, including village stability operations, was the result of a concerted strategic effort from Petraeus.

"I'd say the biggest significant change was not the surge of US forces, but the replacement of [Gen. Stanley] McChrystal with Petraeus," says Seth Jones, an analyst at the RAND Corporation and author of "In the Graveyard of Empires: America's War in Afghanistan."

The positive impact has been less due to troop levels than strategy on the ground, Mr. Jones says. The implication is that as US troop levels come down, the US could refocus its efforts on "white" special operations forces such as the Army's Green Berets who can train local Afghan forces, in combination with counterterrorism strikes from "black" special operations forces like the Navy SEALs and Army Rangers, says Jones. "You could actually get a lot of bang with a smaller footprint, but focused on these efforts."

This approach holds promise, say defense analysts. While the south is improving where the bulk of NATO's 70,000 troops are operating, there remains troubling violence in the east, where powerful insurgent groups such as the Haqqani network operate out of sanctuaries in Pakistan.

"That's what keeps me up at night – the insurgents that continue to have sanctuary in Pakistan with state support," Jones says. "That has the potential to undermine everything."

Mullen acknowledges this point as well, noting that addressing Haqqani network sanctuaries in the North Waziristan area of Pakistan is "central to a long-term solution" in Afghanistan. "What's most bothersome about Haqqani is that they continue to foster a campaign that pushes right up against Kabul," he says.

For now, the Pentagon will be working closely with the White House in the months to come to determine how best to bring an end to the surge that marked the moment Obama made the war in Afghanistan his own.

For now, America's top military adviser acknowledges that there are no clear answers to precisely how many US troops should remain on the ground.

"We don't know what the answer is," he says. "I can honestly say that no one knows what the answer is yet."

Editor's note: This is part of a cover story project that is a report card on the surge, with on-the-ground reports from three facets of the surge: the US military, the Afghan security forces, and the Afghans themselves.