Dams power Turkey's future, but drown its rich history

Loading...

| Allianoi, Turkey

The stunning mosaics, courtyards, and passageways of the 1,800-year-old Roman spa complex of Allianoi were so dear to archaeologist Ahmet Yaras that he named his daughter after the Ilya River that ran by them.

As he now witnesses its waters rise and engulf the ruins he has fought so hard to save, he says their disappearance beneath the reservoir of a new irrigation dam feels like the loss of a child.

"This is the murder of history," says Dr. Yaras, who formerly headed the excavation team that found some 11,000 artifacts during a decade of digging at Allianoi – work that unearthed only 20 percent of the site.

The Yortanli dam is part of an unprecedented hydroengineering program launched by the Turkish government to maintain the country's rapid economic development.

It is also one of the flash points in the battle between Turkey's government and an increasingly vocal lobby of activists and academics who fear the plans will exact a devastating toll on the country's rich historical and ecological wealth.

1,300 new plants to power Turkey's economic development

Mert Bilgin, a professor specializing in energy policy at Istanbul's Bahcesehir University, acknowledges that poor oversight has maximized the environmental damage associated with the projects. But he says Turkey's need to increase its energy output could hardly be more urgent as the country strives to fulfill its dream of becoming a major economic power.

In 2010, energy imports cost $40 billion, accounting for nearly half the country's foreign trade deficit. This cost is set to soar since Turkey needs to double its power capacity by 2020.

"The negative impact of energy expenditures on trade balance, and consequently on the current account deficit, is extremely important for the Turkish economy," says Professor Bilgin. "Many reports point out that Turkey may face electricity shortages shortly if it cannot develop energy infrastructure as much as its economic growth."

The Department for State Hydraulic Works is expected to invest some $71.5 billion in dam building by 2030, an investment that goes well beyond the long-running Southeast Anatolia Project. It includes a program to realize the country's full hydroelectric potential with 1,300 new plants.

New bill would endanger 80 percent of protected land

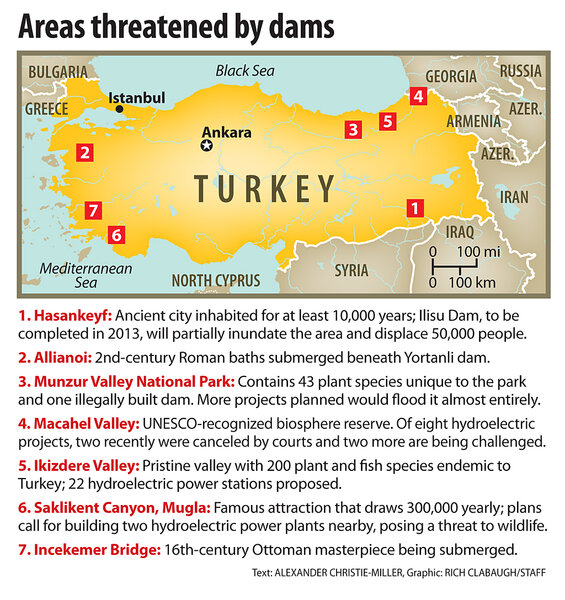

Many archaeological and environmental hot spots have already been threatened.

Now, a nature protection bill redrafted by the government in September and currently in parliament will abolish the country's largest network of nature reserves, endangering 80 percent of currently protected land. It will also do away with a set of regional culture- and nature-protection councils that in the past have sometimes held in check the government's dam-building schemes.

All conservation decisions will be placed in the hands of a committee dominated by appointees of the Ministry of Environment and Forests, the main engine behind the hydroengineering program.

Turkey claims the draft law is part of its efforts to join the European Union, but the EU Commission has condemned the legislation. Some 200 Turkish groups have also come together to oppose it.

Guven Eken, president of the Turkish advocacy group the Nature Association, worries that, if passed, it could trigger "the mass destruction of biodiversity in Turkey" and a wave of government-backed development in formerly protected areas.

The net effect, he says, will be the end of all restrictions: "In the current political climate, we can see that the decisions of this committee aren't likely to be in favor of preserving human culture or environmental diversity. It's going to destroy our cultural heritage, our natural heritage, our quality of life."

Why politicians love big dams

Prof. Serhan Oksay, who specializes in environmental economics at Istanbul's Kadir Has University, says the pursuit of large-scale hydroengineering projects is ingrained in Turkey's political culture.

The founder of modern Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, proposed harnessing the energy of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers more than 80 years ago, and influential past premiers like Suleyman Demirel and Turgut Ozal once spearheaded energy and infrastructure programs while still state-employed engineers.

"Since then, building dams for irrigation purposes or generating electricity has been deemed necessary for building up a prosperous country," says Professor Oksay. "Anyone with the ambition of building a successful political career seems to be in favor of such schemes."

Turkey's leaders have done little to hide their impatience with opposition to dam-building policies. Most vocal is Environment Minister Veysel Eroglu, widely regarded as the driving force behind the current program. Following the decision to bury the Allianoi baths last year, he described them as "just one pillar and a fountain."

'These can be found anywhere,' Mr. Eroglu said. "No one was aware of them before we dug them out. My job is to build dams, but we tried to protect this place."

Still-functioning thermal baths

It's true that when exploratory work started in 1998 as part of a survey for the dam, Yaras had no idea that beneath a field near Bergama lay one of the world's most extensive and best-preserved ancient health settlements.

But once archaeologists found the still-functioning thermal baths, as well as a hospital containing bronze medical instruments from the 2nd century AD, the following decade was consumed by a race to catalog the ruins and force Ankara to scrap the dam.

Authorities first buried the ruins in sand – a move they said would protect the ruins, although archaeologists have disagreed. Then they began flooding the area on the final day of 2010. The rising water is now some six feet deep. Eventually, the baths will sit in nearly 100 feet of silt and water.

"The most painful part may be that we will never know what knowledge we may have found," says Yaras. "I feel like a scientist who was on the verge of a major discovery, only to be banned from his laboratory."

Yaras and others embroiled in this bitter debate surrounding the future of Turkey's natural and cultural heritage doubt the government will concede an inch to conservation demands.

"Allianoi is only an example," says Yaras. "They will ruin many other precious sites."