As Mideast talks begin, Palestinians find unlikely support from Jewish settlers

Loading...

| Walaja, West Bank

As Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu traveled to Washington this week, he carried with him a mix of hopes and fears about what the renewal of Mideast talks would – or should – bring.

One of the more unusual proposals came from Rabbi Menachem Froman: In order to move negotiations forward in an amiable atmosphere, why not send a delegation of rabbis to the West Bank to wish Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas and the Palestinian people long life?

Rabbi Froman, whose suggestion contrasted starkly with a prominent rabbi's sermon this past weekend wishing death to Mr. Abbas, is the most outspoken of a small but growing group of Israeli settlers who seek to bridge the volatile divide with their Palestinian neighbors.

He and likeminded settlers – undaunted by the resistance they've met from the Israeli state, fellow Israeli settlers, and even left-wing Israeli activists and Palestinians themselves – are pressing for Palestinian rights. Their agenda is fueled by a unique mix of ideology and human compassion.

"I'm a citizen of God's country," says Froman, who wants to remain in the West Bank even if it means becoming a citizen of a future Palestinian state. "Whoever is the politician in charge is less important."

A longtime proponent of peace based on religion rather than politics, Froman has close ties with top Israeli officials, the Palestine Liberation Organization, and Hamas. He says he was able to pass his suggestion to Mr. Netanyahu through a mutual friend serving as minister in the government.

The charged divide

Like other religious settlers, Froman believes the West Bank is part of the land that God promised Abraham. But he and other settlers like him also embrace Jewish commandments to treat everyone with compassion and mercy, and so have trouble accepting the hardships imposed on Palestinians daily.

Their efforts are epitomized in their opposition to the 500-mile-long security barrier that Israel has nearly finished erecting since a wave of suicide attacks killed more than 1,000 Israelis in the second intifada that began in 2000.

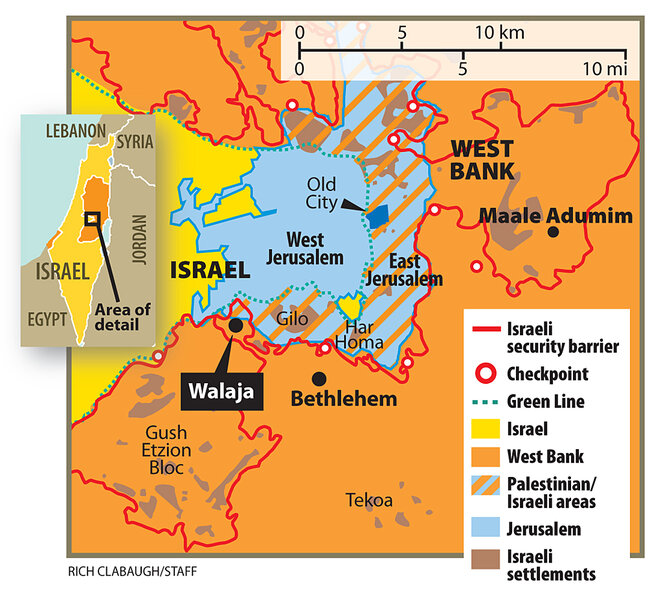

Much of the wall runs through the Israeli-occupied West Bank, dipping into the territory Palestinians claim for a future state in order to include burgeoning Israeli settlements – communities considered illegal under international law. According to the Israeli human rights organization B'tselem, the wall encircles 8.5 percent of all West Bank land.

But Palestinians are skeptical of settler efforts to oppose the barrier.

"The settlers are part of the problem," says Ali Alarej, a Palestinian who leads weekly protests against the wall going up around Walaja, a community that will be cut off from Jerusalem. "Instead of joining our protest, they should get up and move back inside the Green Line," he added after a recent protest, referring to the 1949 armistice line.

Nachum Pachenik, who lives in the West Bank settlement bloc of Gush Etzion, encountered such resistance when he led a group of settlers to join the Walaja protest in April. When the settlers heard locals were preparing to throw stones at them, they abandoned the trip.

Fellow settler Myron Joshua was also turned away from Palestinian protests in the town of Umm Salamuna last year. "I called the [organizer] up, and when he heard I was a settler, there was a problem," he says.

Such cold receptions are a reminder of how hard it is to reach across the charged divide between Israel and the Palestinian territories. It also underscores the mistrust between the two sides as Netanyahu begins direct peace talks Thursday with the Palestinian Authority headed by Abbas.

Halting the wall's construction in Walaja, due to be completed in December, is unlikely. Defense Ministry spokesman Shlomo Dror says Palestinians already appealed to the High Court of Justice four years ago and lost, adding that the barrier is essential to Israel's security.

“We checked a lot of options,” Mr. Dror says. “We can’t say, ‘Don’t build a fence’ and just wait for terrorist attacks.”

Two cups of tea

But settlers like Mr. Pachenik aren't giving up on breaking down the barriers – tangible and intangible – between Israelis and Palestinians.

Pachenik last year founded the Eretz Shalom (Land of Peace) movement to foster settler-Palestinian dialogue, which now has "a few hundred" members, he says. Earlier this summer, he hosted Muhammed Abu Ayash, a Palestinian engineer and peace activist. They chatted over tea and cakes in the cluttered kitchen of Pachenik’s white mobile home, known here as a "caravan," part of an unauthorized outpost.

Unlike the Palestinian protesters in Walaja, Mr. Abu Ayash entertained the idea of settlers staying in the West Bank.

“We cannot split from each other,” he said. “We have the same land, the same holy places, the same border, and the same resources.”

Such dialogue is rare in the West Bank, where settlers and Palestinians live apart, use separate roads, and speak different languages.

“I am ashamed that there are separate roads for Jews and Arabs, and I have rights Muhammad doesn’t have,” Pachenik said.

Indeed, Abu Ayash's hometown of Beit Ummar, near Hebron, is hemmed in on all sides by settlements that enjoy more freedoms than the Palestinian villages. But for now, even just talking is an unusual breakthrough. “We have many things to do, and not just talk,” Abu Ayash said, adding: “When [Pachenik] invites me to visit his home, it gives me hope.”

'You're living here, I'm living here – let's see how to do it together'

Mr. Joshua, the settler who was turned away from protests last year, is on the Eretz Shalom mailing list and also regularly meets Palestinians through the Interfaith Encounter Association.

The association has 29 groups of Israelis and Palestinians throughout Israel, plus two recently formed settler-Palestinian groups over the Green Line. Gush Etzion's branch was founded in late 2009 and meets with Palestinians from around Hebron. About 25 settlers and Palestinians attend the monthly meetings. The second branch, in East Jerusalem, was founded in 2008 and has about 15 Palestinians and settlers from Maale Adumim and Abu Dis.

Joshua sees the growing movement of settlers as ambassadors for finding an informal solution where government leaders have failed. "It's people saying, 'I'm fed up with politics. You're living here, I'm living here, let's see how to do it morally and legally together,' " he says.

The increasing number of settlers involved in Interfaith Encounter Association and Eretz Shalom can be credited in part to a new generation of Jews born in the West Bank, says Froman, the prominent rabbi whose teachings have inspired settlers to interact with Palestinians. The new generation has grown up alongside Palestinians.

"They know the Palestinians not from the point of view of, 'How do they fit into my ideology,' but from direct contact with them," he says.

Skepticism from Israelis

Many fellow settlers don't share the vision espoused by Froman, Pachenik, and Joshua.

Dani Dayan, chair of the settler umbrella organization known as the Yesha Council, says it is "defeatist" to give up on trying to ensure the West Bank is part of the Israeli state.

"The situation is not ripe for a solution," says Mr. Dayan, who lobbied against Israel's 10-month partial freeze on settlement expansion that expires in late September.

Moreover, Palestinians don't want to live alongside the Jewish settlers, says Hebrew University political scientist Yaron Ezrahi, highlighting how West Bank Palestinians have already banned all goods made by Jewish settlers, including plastic furniture and seltzer machines.

Professor Ezrahi says he doubts that settlers can peaceably remain in the West Bank, but "if settlers will fight against the wall for what it does to the Palestinians on a large scale, I will change my mind."