Beyond the Gaza blockade: What drives Israel's Benjamin Netanyahu?

Loading...

| Jerusalem

It was one of those moments in Israeli politics – any nation's politics – in which the numbers just don't add up. Lawmakers had been toiling all night trying to fashion a budget. Now night had turned into dawn and debate into occasional tempestuousness when, at 7 a.m., Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu strode into the Knesset in his trademark crisp white shirt, designer tie, and dark suit.

Fourteen years ago, when he was prime minister the first time around, Mr. Netanyahu likely would have marched straight to his desk, crunched his numbers, applied his macroeconomic theories, and come up with his answers to the budget gap. Not this time, according to Yuli Edelstein, his minister of information and diaspora.

Instead, Netanyahu headed for the back of the room where rank-and-file members sat. He shook their hands, asked about their spouses, inquired about their kids.

IN PICTURES: The Gaza flotilla and the aftermath of the Israeli naval raid

"I saw him shaking hands with all kinds of backbenchers. I looked at this scene and said with wonder, 'Is this the same person from 17 years ago?' " recalls Mr. Edelstein. "Back then, he was too much of a policy wonk to do anything like that."

The scene illustrates one way in which Netanyahu has changed since his first tenure as prime minister from 1996 to 1999. Although perhaps still someone who prefers the lecturer's podium to backroom politicking, he has learned to excel at the glad-handing art of governance, which was remarkably absent the first time around. "In the beginning it was hard for him to understand that outside the world of big ideas you have to do a lot of political homework, to give recognition to people – to members of Knesset, to coalition partners," Edelstein says.

Now it's about being a little less cerebral, a little more congenial. And, perhaps, taking things in stride. "I see him today being more patient and less jumpy, less overreacting to all kinds of things," says Edelstein. "There are people who are a natural at this. He's not."

Other things, however, seem to come easily: Netanyahu's ability to state his case. Even, that is, when much of the world disagrees, as it has with his stance on the flotilla crisis that erupted May 31. From the time he was a student at Cheltenham High School near Philadelphia, where he excelled on the debating team, to his world debut in the mid-1980s when he began defending Israel as its envoy to the United Nations, Netanyahu showed acumen in the persuasive arts. But it's still not clear where he will put these skills to the greatest use – in swaying fellow Israelis to take risks for peace or in convincing the rest of the world why an embattled Israel can't.

From the floor of the Knesset plenum to the door of the White House, from the halls of power in Europe and the Middle East to – perhaps most important – the Muqata in Ramallah where the Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas sits, there seems to be a shared sense of mystery about who Benjamin Netanyahu really is and who he is ready to become. Perhaps he is his father's son, the heir apparent of an ultranationalist wing of Zionism whose founders saw no space – physically, strategically, ideologically – for an independent Palestinian state on the land now controlled by the Jewish-Israeli one. Or perhaps he dreams of following in the bold footsteps of other Israeli leaders – of Likud founder Menachem Begin when he signed a land-for-peace deal with Egypt in 1979 – and hopes to go down in history as a singular leader who ushered in some viable plan to solve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

It may be that he wants both. He wants to be Bibi, as he is widely known here, the man who defends Israel from outside pressure to make concessions that might endanger its survival – which is precisely how he has played his opposition to ending Israel's controversial naval blockade of the Gaza Strip. But he also wants to be Bibi, the man who would become Israel's equivalent of Nixon in China – the last man anyone expected to take a risk for peace with the enemy, and perhaps the only one who could do it.

Daniel Ben-Simon, a Labor Party member of the Knesset and therefore a member of Netanyahu's coalition government, says that anyone who tries to decipher the Netanyahu code will find himself exasperated. "Nobody really knows him. I've followed him for years as a journalist, and I really don't know who this man is," says Mr. Ben-Simon, who left a long career at Haaretz, Israel's liberal, intellectual paper, to enter politics last year. "He might bring us to war or he might make peace with the Syrians. Maybe his fans are right; maybe Netanyahu will deliver. I haven't given up yet."

The few people who are close to Netanyahu say they see a man who has evolved and matured. But probably not converted. "Is he entirely changed? Born-again? No, he's not," says one confidant. "People don't change entirely. But there are changes that come with experience. He's trying to do better this time. I think it's possible that he's ready to break through politically, but I'm not sure it's possible, given the limits we see on the Palestinian side."

If there's a new Bibi who has become more open to compromise, it was the old Bibi who seemed to be archly on display in the fallout over the flotilla crisis, sounding a note both defiant and defensive. Given Hamas's ongoing attempts to import arms to Gaza, he argued, Israel has an inalienable right to impose a naval blockade on the Gaza Strip. Israel's soldiers were just acting in self-defense when, in commandeering one of the six ships while in international waters they responded to attacks on deck with live fire, killing nine people.

Publicly, he has rejected calls for an independent international probe of the incident and continues to blame the world for applying "double standards" when it comes to Israel. But privately, he has told US officials he is willing to consider new arrangements on access to Gaza. And on June 10, he eased the blockade, allowing in previously banned food items in an attempt to mollify world criticism.

These different faces of Netanyahu suggest a complex man whom even confidants find difficult to read. His handling this summer of a series of incendiary issues with global implications – the flotilla crisis, the proximity talks with the Palestinians, and the dwindling months left to a freeze in West Bank settlement construction – will test how much he's evolved as a leader and an ideologue, not to mention his relations with Washington. More important, it may define whether he will go down as a statesman or a nationalist.

this time last year, on balmy June evenings, Netanyahu was getting ready to deliver the speech of a lifetime. He and his aides were hammering out the final version of the text they knew would become the most important landmark in his political career so far. He was preparing for an address at Bar-Ilan University – a bastion of political and religious conservatism in a world of more liberal Israeli academia – in which he would go where no Likud premier had gone before. He would declare his support for a two-state solution to the conflict, specifically referring to a Palestinian state.

He knew that many in his own rightist party would find this unacceptable. And so, the day before the speech, he sat down with Likud members and tried to use his best tool: the power of persuasion. Sworn opponents to this two-state concept were not surprised, but neither were they swayed. "I asked him not to use the words 'Palestinian state.' I was very direct with him and said he would be making a huge mistake because if you say it you'll be playing into the post-Zionism of the left," says Danny Danon, a young Likud member. "Unfortunately, he didn't take this advice. But I'm sure that deep inside he knows it's not going to happen."

Ambitious, assertive, articulate, and just shy of 40, Mr. Danon doesn't seem so far from the figure that Netanyahu himself cut 20 years ago when he was rising to international prominence. Though Netanyahu had already served as Israel's ambassador to the UN from 1984 to 1988, the rest of the world seemed most impressed when he deftly argued Israel's case during the Gulf War nearly two decades ago – occasionally donning a gas mask in the middle of a television interview when a new Iraqi Scud missile was headed in Israel's direction – and then continuing to make his point.

Netanyahu's focus on protecting an Israel under threat – then from Iraq, now from Iran, Hezbollah, and Hamas – has dominated nearly everything he has done in public life. "Every living organism depends on its ability to recognize the threat to its life in time," Netanyahu said last month in a speech to Russian journalists. It's a maxim he quotes often. Of two political portraits on the wall in his office, one is of Winston Churchill, whom Netanyahu admires for his perception of the Nazi threat long before other Allied powers, including the US. (The other photo is of Theodor Herzl, considered the founder of modern Zionism.)

Indeed, fending off foes at home and abroad has long been Netanyahu's forte. In the past, that acumen in assessing threats has sometimes translated into a siege mentality in which Netanyahu was portrayed in the Israeli media as mistrustful and paranoid. (In a 1997 interview with the Monitor, he opened with the words, "OK, shoot to kill.")

It's a theme that replays itself over and over again. Netanyahu has taken the world's questions about the legality and morality of Israel's naval blockade on Gaza and morphed it into an international assault on Israel's right to self-defense and, by default, right to exist. "Today," Netanyahu told an elite army unit he visited on June 8, "Israel's very right to defend itself is under attack."

This March came in like a lion: The visit of US Vice President Joe Biden was derailed by an embarrassing announcement that Israel would build housing for several thousand Jews in East Jerusalem. It did not go out like a lamb. Things worsened when Netanyahu, during a visit with President Obama, got a palpably cold shoulder at the White House.

But the "tough love" – a term many veteran Middle East policymakers in Washington have come to use as a catchphrase for taking a firmer hand toward Israeli ambivalence and foot-dragging – got perhaps too rough and backfired. Members of Congress, and pillars of the American-Jewish community such as Elie Wiesel, began to chastise the administration for taking too harsh an approach and alienating Israel.

Other things began looking up for Netanyahu as well. In April, he survived a serious challenge from within his own Likud Party. In May, Israel was accepted to join the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a major nod toward Netanyahu's economic reforms. Long-sought Israeli-Palestinian proximity talks finally began.

Then, in mid-May, Mr. Obama told members of Congress that he'd made some missteps entering the Middle East minefield and, he joked, might have lost a few fingers. Underscoring Washington's move to mend fences, Obama's chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel, hand-delivered an invitation for a White House meeting ahead of Obama's parley with Mr. Abbas. Those given to gloating said Bibi had wrestled with the giant and won – or at least had not been cowed. Those given to more diplomatic language said it was a sign of accepting that Netanyahu is here to stay.

"Perhaps there were hopes in Washington at one point of a different government constellation, one that would include the Kadima Party," says Zalman Shoval, a veteran Likud member, former Israeli ambassador to the US, and head of the prime minister's Forum on US-Israel Relations. "They realize now that this is not going to happen. The coalition is very solid, at least at present, and they have to deal with him whether they like it or not. So they decided to warm up the relationship."

But then came the raid. "Man plans, God laughs," holds a famous Yiddish saying, one that Netanyahu's ancestors in Eastern Europe probably knew well. (His ancestry is directly linked with a revered religious sage known as the Vilna Gaon, or genius, of Poland.) Instead of reaping the benefits of victories large and small won over the past few months, Netanyahu now finds himself on the defensive domestically and internationally – and jousting with Washington once again. It's a position he knows and plays well.

In his controversy-clouded first term, Netanyahu ran into a crisis early on when he allowed the opening of an underground tunnel, which ran beneath Jerusalem's holy places and exited in the Muslim quarter of the Old City. Ehud Olmert, then the mayor of Jerusalem, got the go-ahead from Netanyahu. Three days of deadly riots ensued.

While campaigning for the Labor Party a few years ago, Ami Ayalon, the former head of the Shin Bet, Israel's internal security service, blamed both of them for failing to cope with the fallout. A leader should be evaluated, Mr. Ayalon said, "according to the way he handles moments of crisis and pressure." He continued: "When the Western Wall tunnel opened in 1996, and the riots and pressure began, I know where Bibi and Olmert were. They were not there; they disappeared."

That negative image, one of fumbling or fading into the woodwork during crises, has dogged Netanyahu for years. Behind the smooth-talking exterior and the seamless, self-assured answers he can provide in flawless English or Hebrew is a man who is easily rattled, critics say. But longtime friend Dore Gold, who served as his ambassador to the UN in the 1990s, says it's not an accurate portrayal.

"There's a myth that he's nervous under pressure. But I've seen him be very firm," says Dr. Gold, now head of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. Gold says he has learned much from his previous experiences as prime minister and foreign minister, as well as his stint as opposition leader in between. "He knows what it's like being at the apex of power. That's an advantage. I think now there are fewer surprises. He knows what's essential and what's just noise."

The botched flotilla raid was certainly unexpected. Netanyahu has surrounded himself with a tight group of six ministers, known as the "septet." The decisionmakers signed off on what they thought was a straightforward commandeering of the flotilla, as has been done with previous boats carrying activists trying to reach Gaza. Now, of course, everything looks different.

"He's trying to manage his way out from something he didn't even consider could happen," says Dan Meridor, a veteran Likud colleague who is deputy prime minister and minister of intelligence and atomic energy. "The decision was made to carry this out with actions that, judging on past experience, seemed routine, and which was presented as something that could be dealt with without violence. Whether it was a smart move or not, there was no intent to harm."

At 80, FORMER Ambassador Shoval has a half century of experience in Israeli politics; few active Likud Party figures have had as many years to observe and work with Netanyahu as he has. That is, unless one counts the luminaries of Likud's ideological forerunner, the Revisionist Zionist movement, in which Netanyahu's 100-year-old father, Prof. Benzion Netanyahu, was once a prominent figure. The movement, founded by Zeev Jabotinsky, attracted secular nationalists who were opposed to the practical (read conciliatory) Zionism in the style of David Ben-Gurion, who became Israel's first prime minister. Instead, they promoted the idea of a Greater Israel, arguing for a Jewish state on both sides of the Jordan River.

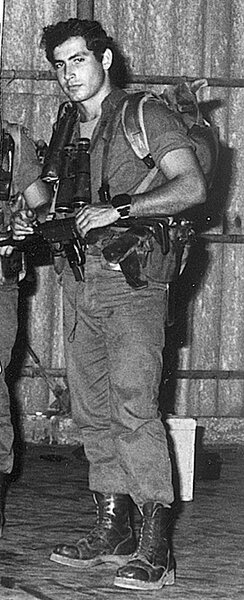

Netanyahu's hard line on terrorism may also have been shaped by having grown up in the shadow of his older brother, Yoni, the head of an Israeli army commando unit. Yoni was killed in 1976 in Uganda during Operation Entebbe, in which Israeli soldiers overtook a group of Palestinian hijackers who had seized an Air France plane.

Although the Greater Israel ideology has all but died out from mainstream rhetoric, some in the extended Netanyahu family – and that of his wife, Sara – still hold its ideals dear. It is because of such a right-wing pedigree that many doubt whether Netanyahu is sincere about his ostensible conversion to the concept of two states for two peoples.

Shoval insists that Netanyahu is more practical and less dogmatic than many would believe. "I always said that he was a pragmatist, much beyond some of his friends in the party," Shoval says.

But the fact that it took so much toiling on the part of Obama and his Middle East peace envoy, George Mitchell, just to get to proximity talks is seen as a downgrade from direct negotiations in the past. If there's one thing that many Israelis and Palestinians seem to agree on these days, it's a pessimism about the proximity talks.

"An agreement can only be an outcome of very detailed direct negotiations, and right now that doesn't look like something that will happen in the near future," Shoval says. "The term proximity is a euphemism. Proximity means nearness and what we have here is talks by remote control. It means the Palestinians are not ready to sit down and talk directly."

Palestinians say that is hardly the problem. Jibril Rajoub, a member of Fatah's central committee – a body that holds sway over Abbas – was one of the Palestinians best poised to observe Netanyahu when he was in power in the 1990s. Mr. Rajoub was then the Palestinian Authority's security chief for the West Bank, based in Hebron.

Netanyahu was openly against the Oslo Accords but promised to uphold them once elected. As such, the task of pulling out of Hebron, the last West Bank city Israel was still fully occupying in 1996, was now in his lap. He insisted on renegotiating the accords over several months until the sides reached a new agreement, called the "Note for the Record," in early 1997. It produced a division of the city that neither side is happy with – especially Palestinians, who can't enter once-vibrant areas of Hebron because of their exclusive use by about 500 Israeli settlers.

"The problem, then as now, is that Netanyahu can only see everything in terms of Israel's security needs and does not realize that the Palestinians need security as well," Rajoub says. "We feel we're trying to accommodate the American position in the Middle East, which for the first time has exerted pressure on Israel. But will Netanyahu act modestly and respond to the positive attitude of the Palestinians? I think neither his difficult character nor his alliance with the settlers and the extremists will allow him to move toward peace."

Mr. Meridor, once referred to as one of Likud's "young princes," insists Bibi has come far from where he started. But the maximum he is willing to give, he says, may not meet the minimum of what Palestinians feel entitled to receive. "When someone that high, of that stature, a leader of a nation and a political party, proposes that we are moving towards two states, it has a very important effect on the politics of this country, on the philosophy, on the Weltanschauung," says Meridor.

"I say this because I think he meant it. Does that mean he will go the length of the whole road necessary to get an agreement? I'm not sure. And I'm not sure that even I am ready to go as far as the Arabs want, although I'm ready to go a very long way. But I think he has crossed a bridge."

IN PICTURES: The Gaza flotilla and the aftermath of the Israeli naval raid

Related:

- Israel eases Gaza blockade, allowing building supplies and ketchup

- Israel announces Gaza aid flotilla inquiry, Turkey not satisfied

- Israel's Netanyahu balks at UN investigation of Gaza flotilla raid

- Never mind the 'Freedom Flotilla.' Is Israel's Gaza blockade legal?

- Why Israel ignores global criticism of Gaza flotilla raid

- Readers weigh in: Israeli blockade of Gaza: What would you change?