Christian aid worker purge? Morocco orders dozens in five cities to be deported.

Loading...

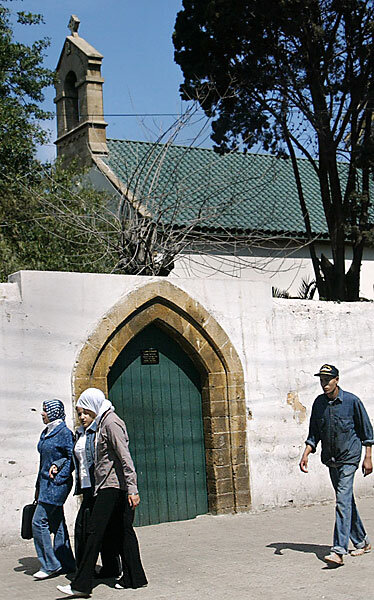

| Rabat, Morocco

Moroccan authorities have ordered dozens of foreign Christian aid workers deported in at least five major cities this week, calling into question an unspoken but long-standing truce between missionaries and their Muslim hosts.

“This is a change in policy from the top of the government,” says Jack Wald, who has spent 10 years as pastor of Rabat International Church, a protestant congregation here in the capital. “It’s like going to sleep, waking up, and all of the sudden you’re in a different country.”

The largest incident took place at an orphanage for 33 abandoned children in the Middle Atlas mountains on Monday. Moroccan police showed up in the village of Ain Leuh, located 50 miles south of the ancient city of Fez, and separated orphans from their adoptive parents before delivering a grim piece of news: the Moroccan authorities had accused the volunteers of spreading Christianity – a crime in this overwhelmingly Muslim nation.

Witnesses described an anguished scene as Dutch, British, Kiwi, and American volunteers hastily emptied households under stormy skies and hugged weeping Moroccan kids for the last time.

“The wind was howling... but that was nothing compared to the wailing of the children,” said one foreign witness, who asked not to be named, saying she feared reprisals from Moroccan authorities. “I’ve never heard a sound like that in my entire life.”

The deportation of aid workers from Morocco highlights both the major role that Christian aid organizations play in a number of Muslim nations and local anxieties that aid efforts are cover for covert proselytizing. On Wednesday, gunmen killed six Pakistani staffers for the Christian aid group World Vision working on a development project for survivors of a 2005 earthquake outside of Islamabad. World Vision spent $1 billion on aid projects around the world in 2009.

Government: It's not just Christians

Moroccan officials say they’re merely targeting isolated instances of law-breaking.

“This is not a move against Christians, it’s a move against people who don’t respect the law of this country,” said Morocco’s Communication Minister Khalid Naciri in a telephone interview.

But Christians see a sudden, coordinated campaign that has reversed an unwritten understanding.

In principle, Christian groups are allowed to do charitable work here so long as they don’t try converting Muslims, who make up 98 percent of the population. In practice, hundreds of foreign Christians have been quietly spreading their faith in Morocco for years, says Jean-Luc Blanc, head of the Casablanca-based Evangelical Church of Morocco.

In the past, Mr. Blanc said the government would typically deport one or two missionaries per year whom it judged to have crossed the line. But in his nine years here, Blanc says he hasn’t seen a mass expulsion like this. “Since I’ve been in Morocco, never,” he said.

While Morocco periodically expelled numerous Christian missionaries during the nationalistic decades following its independence from France, the past 10 years under King Mohamed VI have been marked by relative tolerance. That appears to have changed, Christian leaders in the country said.

Another wave of expulsions?

In the past week, police have expelled foreign Christians suspected of seeking converts from the cities of Fez, Tangiers, Essaouira, Rabat, and Marrakesh, according to interviews with pastors in several cities.

In recent days the Moroccan government has marked at least “several dozen” foreign nationals for expulsion, said one Western official who requested anonymity.

The spokesman for the US Embassy in Rabat, David Ranz, confirmed that Americans are among those Christians whom Morocco has declared unwelcome. Mr. Ranz declined to release specific numbers or names, but said Moroccan authorities have told the embassy “additional people will be expelled.”

Orphanage office manager: 'We weren't proselytizing'

Mr. Naciri, the government spokesman, said people of all faiths remain welcome to worship freely in Morocco so long as they don’t seek to “undermine” Moroccan Islam.

He cited recent moves the government has made against Islamist groups as evidence Christians aren’t being singled out, saying “the Moroccan government today deals harshly with anyone who manipulates the religion of the people.”

But the expelled volunteers from Village of Hope orphanage insist they were operating within the law.

“The fact of the matter is we weren’t proselytizing,” says Chris Broadbent, a New Zealander who managed the orphanage’s office until Monday, when he and his family fled to Spain. “We understood the rules.”

At the orphanage school, the children spoke Moroccan Arabic, studied the Koran, and learned Muslim prayers as stipulated by Moroccan law, Mr. Broadbent says. Outside of the classroom, it’s true Christians were raising the children in Christian households, but Broadbent says this was a fact about which no Moroccan official could pretend to be surprised.

“It was a clear, open, discussed, confirmed agreement with local authorities,” he says by phone. “We were looking after these children because no one else would.”

Another orphanage awaits next moves

A similarly delicate balance holds at another, older orphanage called Children’s Haven, run by Christians near the town of Azrou in the same region of Morocco.

“For the most part, the authorities think of us as doing a charitable service for Morocco,” says Jim Pitts, an American who’s been working with Children’s Haven for 51 years. At the orphanage, 10 foreigners are currently caring for 30 Moroccan children.

In recent days Moroccan investigators have visited the facility, says Pitts. He and his staff came here to do charitable work not proselytize, he maintains, adding that so far police have found nothing to contradict this claim.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen with us,” he said. “We’ll see.”