For some Iraqi war refugees, business is booming

Loading...

| Amman, Jordan

When Ali Hussein al-Hassona found out his father had been shot, he decided he'd had enough of Baghdad. Like thousands of Iraqis in 2005, he moved his family – including his father, who survived – to Amman.

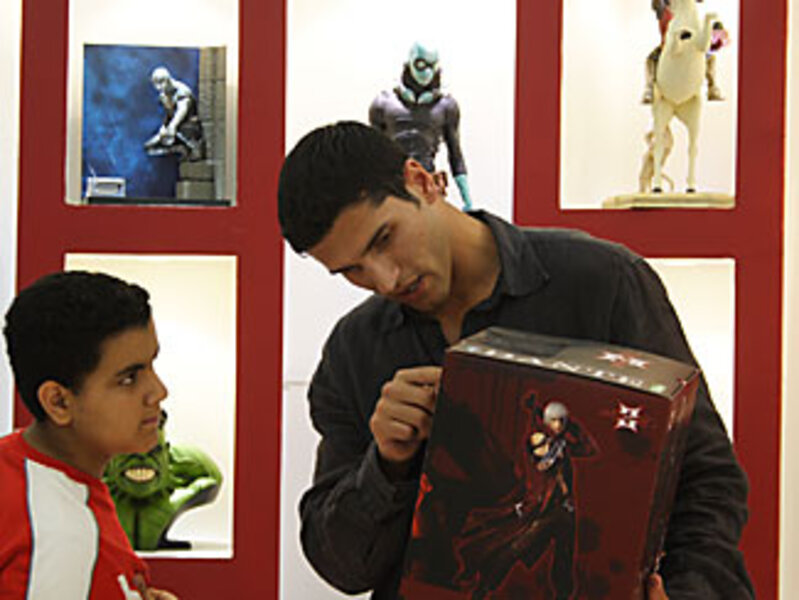

Oxford-educated and a former basketball player, Mr. Hassona took advantage of the move to turn an old enthusiasm into a job. He sank 50,000 Jordanian dinars of personal investment (about $70,000) into opening Jordan's first film and sports collectibles shop, Unnecessary Necessity.

Now giant busts of Sauron, from The Lord of the Rings, and statuettes from X-Men and The Matrix glower from his display cases at shoppers in the gleaming white corridors of one of Amman's most upscale malls. Hassona's business is booming – he has partnered with a Jordanian investor to open another, larger, store and his store now offers wireless Internet and online shopping assistance.

Though the media has focused on the plight of the poorest displaced Iraqis, they are only part of the story. For others, Jordan's security, infrastructure, and open investment climate have created an opportunity.

The only large-scale quantitative survey of Iraqis in Jordan, done in mid-2007 by the Norwegian nongovernmental organization Fafo in collaboration with Jordan's government, found that Jordan wasn't hosting as many Iraqis as once thought – probably less than 250,000.

More than half the Iraqis surveyed by Fafo said they had valid residence permits, meaning they can legally stay in Jordan, which makes it easier to find work, and 21.5 percent said they were employed – compared with 35 percent among Jordanians, according to official figures.

In an increasingly tough economic climate, Iraqi cash, labor, and investment are playing one small part in keeping Jordan's economy strong amid a global economic slowdown.

"The Jordanian economy is doing well, especially in light of the global situation," says Aasim Husain, assistant director of the International Monetary Fund's (IMF) Middle East and Central Asia department.

A major reason for this has been the cushioning effect of foreign cash and investment, economists say. Foreign investment in Jordan has grown from less than $100 million in mid-2002 to more than $3 billion in 2006, according to (IMF) figures. This, along with foreign investment in the stock market, has been a key factor in financing Jordan's large deficits and building up its currency reserves.

While most of this investment comes from Arab Gulf states, Iraqi refugees – who fled Iraq with as much of their life savings as they could – play a role, too, says Mr. Husain.

Some of that goes to small enterprises like Hassona's store, and coffee shops and art galleries that Iraqi refugees have opened in their new neighborhoods.

But much larger businesses have also landed in Amman because of the war, many of them started by Iraqis with long-standing business ties to Jordan.

Mazin Ayass has been living in Jordan since 1990. He moved his auto-parts business out of Baghdad during the first Gulf War, and spent the embargo years of the 1990s smuggling auto parts into Iraq by sea, evading United Nations inspectors.

He'd planned to return to Baghdad after the US invaded in 2003, when the former head of the Coalition Provisional Authority, L. Paul Bremer, declared the country "open for business." But the deteriorating security situation and lack of infrastructure there soon changed his mind, and he shifted his planning to Jordan.

In 2008, in an industrial area outside Amman, he laid the cornerstone for one of the region's first automobile manufacturing plants. So far he's brought in $31 million from foreign and local investors, he says. If all goes according to plan, Ayass Motors will have a partial assembly line running in a year and be ready to move to complete local manufacture by 2013.

But all this type of new investment isn't enough to completely shield Jordan from the global downturn. "Jordan has always had a boom-and-bust economy," notes Pete Moore, who teaches political science at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland and specializes in war economies. Nearly every regional crisis has caused an economic expansion in Jordan, he says, but for the most part, the benefits have only lasted as long as the crises themselves.

Local experts have complained that productivity and growth are not increasing on a par with the level of foreign investment. One of the country's leading economists, Yusuf Mansur, wrote in a recent column in The Jordan Times that the problem might be inflated investment figures or unproductive investments, or both.

To keep Jordan's boom going, economists say, the country needs growth industries that keep skilled workers in the country.

"It's precarious," says Scott Lasensky, a researcher for the United States Institute of Peace, "but it's no more precarious than Jordan has been" in the past. "As long as Baghdad remains unsafe, Amman is going to reap a whole series of benefits."