Is life for Iraqis improving?

Loading...

| Baghdad

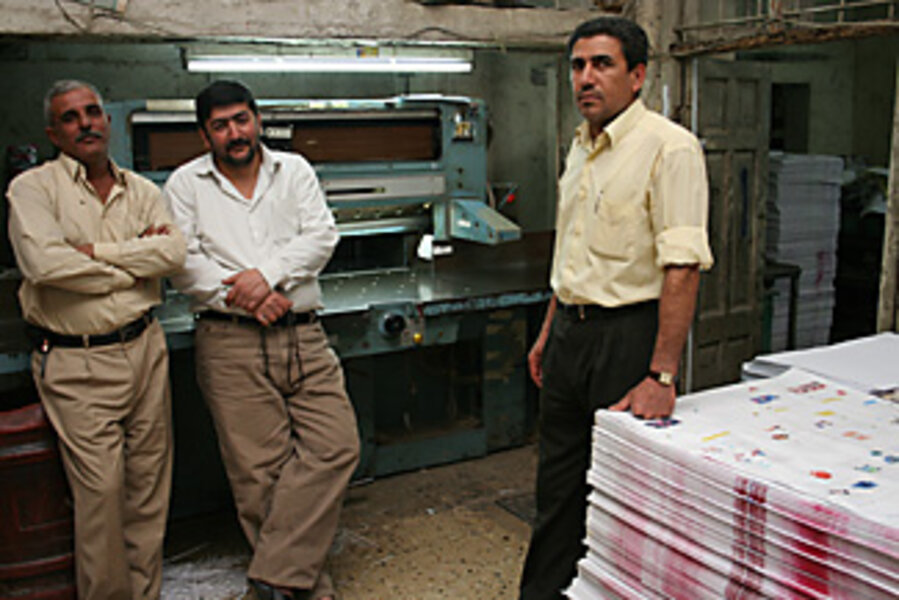

Five years ago, every textbook printed at the Al-Saadoun publishing company had to have a color photo of Saddam Hussein on the first page.

On a recent morning, the noisy printing presses were churning out thousands of booklets promoting the ideas of Shiite Muslim clerics. That would have been unthinkable under Mr. Hussein's regime.

For company owner Muwaffaq Abu Hamra and his prominent Shiite family, the fall of Hussein means religious freedom – the ability of more than half the nation's population to publicly practice their faith without official persecution.

"The Americans did what we could not do: they removed Saddam," says Muwaffaq. "We are indebted to them for that. But we are now close to forgetting this good deed because of the suffering of the past five years."

The experiences of Muwaffaq's family mirror the hardship and determination of many Iraqis since the US invasion of Iraq on March 20, 2003. Muwaffaq, like many of his countrymen, today finds fresh hope in the significant drop in violence and sectarian killings over the past few months.

When asked how they expect things to be one year from now, 45 percent of Iraqis said things would be somewhat better or much better, according to the results of a poll commissioned by the BBC and ABC News and released Monday. That's up from 29 percent six months ago, but lower than in 2005. The poll shows that Shiites and Kurds are more optimistic than Sunnis.

But many Iraqis and outside analysts regard the current situation as little more than a fragile cease-fire unless the political order that has been cemented over the past five years is changed. The inability of the Shiite-dominated government to move forward on issues ranging from sharing oil wealth to sharing power with Sunnis is blamed for fragmenting and polarizing the nation in a way never seen before in its contemporary history.

Era of free speech and religion

Few appreciate the distance Iraq has traveled in terms of political and religious freedom more than members of the Abu Hamra family, who are devout Shiites.

Behind a warren of towering concrete blast barriers, workers in their Baghdad printing plant are producing newspapers of all leanings. In Hussein's day, there were only state-sanctioned newspapers. Today, there are 268 privately owned newspapers and 54 commercial TV stations.

The plant is also producing booklets and posters commissioned by an association belonging to Shiite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr. The walls are teeming with religious slogans and posters of revered Shiite figures past and present, put up by employees.

All of this would have led to the closure of the business, and possibly the execution of all the employees and their extended families, during Hussein's rule, according to Abu Hamra. Back then, government agents inspected his publishing house three times a day to make sure no prohibited materials were being printed.

Muwaffaq's brother-in-law, a nuclear-energy engineer, was executed in 1982 for suspected membership in Dawa, a conservative religious party that was working with Iran to overthrow Hussein's secular Baath Party regime. Today, Iraq's Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki heads the Dawa Party.

But religious freedom doesn't pay the bills or keep their families safe. Muwaffaq and his brother Khaled are struggling to keep open the business started by their late father in 1931. Before the war, they had four printing plants and hundreds of employees. Today, they have two plants and 42 employees.

A brother kidnapped

Their darkest days came three years ago. Their brother Fahim, another partner in the business, was kidnapped in December 2004. He was killed by his abductors even after the family paid a ransom of $120,000.

That same year, two employees and several associates were also kidnapped for ransom. The family paid large sums of money to militants and criminals to get back supplies stolen on the road between the Jordanian border and Baghdad.

Since 2003, thousands of Iraqis, particularly middle-class professionals and business people, have been kidnapped for ransom and were either killed or freed. More than 2,200 doctors and nurses have been killed and more than 250 kidnapped since 2003, according to official Iraqi sources cited by the International Red Cross Committee (ICRC) in a report released Sunday. Of the 34,000 doctors registered in 1990, 20,000 have left the country, according to the ICRC, contributing to the crisis in the country's already crumbling health-care system.

The pace of kidnappings has slowed, but it continues in major cities.

Last week, the last remaining neurologist in the southern Iraqi city of Basra was found dead after he had been kidnapped. And the body of Iraqi Archbishop Paulos Faraj Rahho was found in Mosul after being held for two weeks by a group that demanded a $1 million ransom. Christians and other minority communities in Iraq have been hit particularly hard over the past five years.

Iraqis also continue to be killed, maimed, or wounded, often in the crossfire between insurgents and coalition troops. But the greatest loss of life has been blamed on Al Qaeda in Iraq, seen as the source of most of the suicide and car bombings at public places such as markets and mosques.

Some 24,000 Iraqi civilians died in 2007, an average of 66 per day, according to Iraq Body Count, a group that compiles its figures using public records and media reports. But security is improving. So far this year, the groups says that Iraqi civilians are dying at less than half the rate of 2007.

Getting their families out

In January 2005, following the kidnapping and murder of their brother, Muwaffaq, his parents, and 11 siblings along with their families fled to Amman, Jordan.

The United Nations High Commission for Refugees estimates that as of December 2007 there were 4.4 million displaced Iraqis, including 2.5 million inside the country and 1.9 million in neighboring nations.

Some Iraqis have returned as the violence has ebbed. But Abu Hamra has left his wife and five children in Jordan. His two brothers, Khaled and Naim, also won't bring their families back because they say it's not safe yet. In the BBC/ABC News poll, 54 percent of Iraqis said it's not the right time for refugees to return.

So, Muwaffaq and Khaled shuttle back and forth between Iraq and Jordan – two weeks here, two weeks there. How sure are they that their business in Iraq will survive? They're hedging their bets. They have opened a new plant in Jordan and plan to open another in the relatively stable Kurdistan region in northern Iraq.

One of the biggest challenges facing their business is corruption, which they say is much worse now than under Hussein.

Muwaffaq says that all government contracts today are rigged. Officials routinely collude with his competitors to share the proceeds of inflated bids, he says. One competitor even issued death threats to everyone not to participate in the bidding on a recent health ministry contract.

Judge Radhi Hamza, the former head of Iraq's Commission on Public Integrity, estimated during a US Senate hearing last week that $18 billion in public funds have been lost to corruption, and that's just for the 3,000 cases his commission investigated between 2003 and 2007. He said this does not include the losses from smuggling and theft in the oil sector and the estimated $8.3 billion worth of fraud cases officially "forgiven" by ministers and the prime minister.

US reconstruction money has been also grossly misspent, according to Ali Baban, Iraq's minister of planning and development, citing just one incident in which the US awarded a $20 million bridge-repair contract that ended up costing the contractor only $1 million.

Should the US stay?

Back in the printing plant, talk turns to the role of US forces. Dhia Mahdi, one of the company's longest employees, blames all of Iraq's problems on the Americans.

"The Americans have destroyed this country," he says. "They have divided the nation. Their policy is divide and conquer."

Surveys show Iraqis' views on the US's continued role as mixed. Sixty-one percent say the US presence in Iraq is making the security situation worse. But when asked if the US should leave now, only 38 percent say, "Yes." And 76 percent said they wanted the US to provide training and weapons to the Iraqi Army; 80 percent wanted the US to participate in security operations against Al Qaeda or foreign jihadis in Iraq.

The Abu Hamra brothers say that US forces should leave Iraq now. "Nothing is going right [in Iraq]," says Khaled, who thinks it's time for the family to sell the business and leave Iraq.

The brothers find life in Baghdad arduous. They live at their parents' home. The commute to the printing plant used to take 10 minutes prior to the war. Now, weaving through police check points, blast barriers, and streets clogged with VIP convoys and security details, it takes them nearly two hours. Their parents' home, in a mixed Sunni-Shiite neighborhood that before the war was a gathering place each weekend for the extended family, is now inhabited only by his ailing mother and one of his sisters. Their father died in Jordan in 2006. Most of the rooms in the home are locked.

Most male members of the family now carry weapons for protection. "There is no law to protect you," says Ali, a teenage nephew who owns a pistol and an AK-47.

They have experienced the sectarian violence that flared after the destruction of the Shiite Askariyah mosque in Samarra in February 2006. Muwaffaq recounts how one of his Sunni employees was kidnapped in the summer of 2006 and that he then received a call from a leader in the Mahdi Army, the militia of Mr. Sadr, which is accused of the worst sectarian atrocities. The caller rebuked Muwaffaq for hiring a Sunni. The man was later freed.

His sister Souad, a principal at a school in Baghdad's Dora district, had to leave her job and move to a predominantly Shiite section of town after receiving threats in 2006 to leave the area, which has become almost entirely Sunni.

But Muwaffaq has an abiding faith in Iraqis to get beyond those differences. His wife is Sunni, and many of his brothers and sisters have married Sunnis. "We've never asked if our neighbors are Sunnis or Sabeans. People can live together."

Laith Kubba, a director at the National Endowment for Democracy in Washington and a former Iraqi government spokesman, agrees. "It's most misleading to assume that the current violence and conflict among Iraq's communities is rooted in the country's history. Intermixed neighborhoods and marriages testify to the contrary," he says. But the pattern of violence may be difficult to break, he notes. "The levels of sectarian conflict are unprecedented in the region. Those who caused and benefited from sectarian and ethnic strife will not help resolve it."

Mr. Kubba says the only solution is for the US to use "arm-twisting, incentives, and harsh deterrents," and the influence of regional powers such as Iran, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia to break the current gridlock caused by a "weak dysfunctional state and a system that rewards identity politics."

In the meantime, Iraqis like Muwaffaq cling to a hope for better days. One-third of his employees are non-Shiite. "The will of the people to live together can ultimately be stronger than anything," he says.

Each day, on his drive to work, he passes 12-ft.-high concrete blast walls, many of them now painted with idyllic scenes or plastered with posters urging reconciliation. There's one with a message that reinforces his view: "Our journey is long, but Iraq remains more important than our differences."