Baghdad book market revives after devastating bomb

Loading...

| BAGHDAD

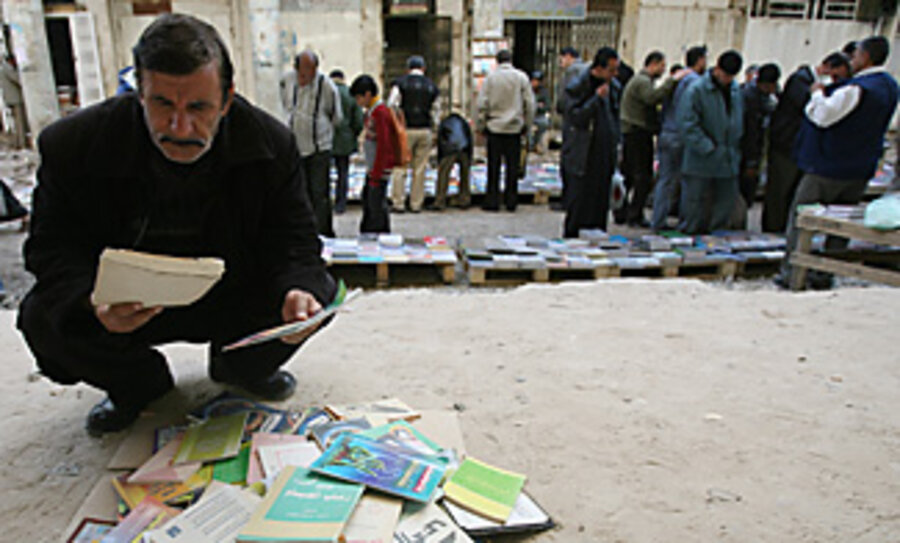

Dusty books lie on flattened cardboard boxes on a sidewalk buried in litter and building debris. Their vendors hunch over and sip hot black tea to fend off the cold. What matters is that they're here.

Amid wreckage, deserted buildings, and the devastated Shahbandar coffeehouse, the Mutanabi Street book market is reviving. A microcosm of today's Baghdad, it attests to a hope for better things now that violence in the capital is noticeably down.

Through Saddam Hussein's oppression, the US-led invasion of 2003, and the ensuing tumult, the Mutanabi market – started by middle-class Iraqis during the crippling 1990-2003 UN sanctions – never ceased to be a favorite Friday hangout for intellectuals, artists, and students.

But when a car bomb ripped through the market on March 5 last year, many thought its days were over. Blamed on Al Qaeda militants, the attack killed 38, wounded 100, and wiped out dozens of bookstores, stationery shops, and presses. The burning stench hung in the air for days. But it did not stop Sunni, Shiite, and Kurdish vendors from continuing to work here in harmony.

"The bomb did not change the way we feel about each other in the market," says Atta Zeidan, a secondhand-book seller.

In response to the attack, authorities banned vehicular traffic from Mutanabi Street, put up blast barriers and checkpoints, and sent in US troops to calm the panicked traders and assure them of reconstruction funds.

Mutanabi vendors say at least 10 of them were killed in sectarian violence during a burst of Sunni-Shiite vengeance killings in 2006. However, they say, interfaith relations on the street remain good, largely because the killers were generally viewed as outsiders and because those killed were known extremists.

Now, an ambitious plan to restore Mutanabi Street and its historic buildings is under way, but traders complain that work is slow and sometimes shoddy. Salah al-Ardawi, a Baghdad municipal spokesman, denied the charge, but acknowledges that the work is sometimes disrupted by insurgent attacks elsewhere in the city.

Concrete structures damaged by the bombing and fire are being reinforced. The asphalt street is to be tiled over. The Shahbandar coffeehouse is being rebuilt virtually from scratch.

The shoppers who initially stayed away have since drifted back, though their numbers are still down.

"People must eat, so they will still shop at food markets that have repeatedly been hit by attacks," says bookseller Zein al-Naqshabandi.

On the other hand, Mohammed Hanash Abbas, who lends textbooks to students for a fee, says things are better now. "Hardly anyone attended classes last year because of the violence," he says. "This year, it's different."