Reaping benefits beyond better prison menus, inmates grow their own food

Loading...

Scanning a prison menu is a bleak task. Common food items range from nutraloaf – a mishmash of ingredients baked into a tasteless beige block – to, rumor has it, road kill. The substandard quality of food at some correctional facilities has led to protests and hunger strikes, as in summer 2013 when nearly 30,000 California state prisoners refused food to demand, among other things, fresher and more nutritious meals.

But some states, along with correctional authorities and prison activists, are discovering the value of feeding prisoners nutrient-rich food grown with their own hands. Prison vegetable gardens, where inmates plant and harvest fresh produce to feed the larger prison population, are on the rise in correctional facilities from New York to Oregon.

In addition to being a cost-effective food source, the gardens are seen as a way to save money on healthcare for prisoners struggling with diabetes, hypertension, and other ailments. But the gardening itself provides opportunities for personal growth, as inmates learn how to plant, raise, and harvest crops.

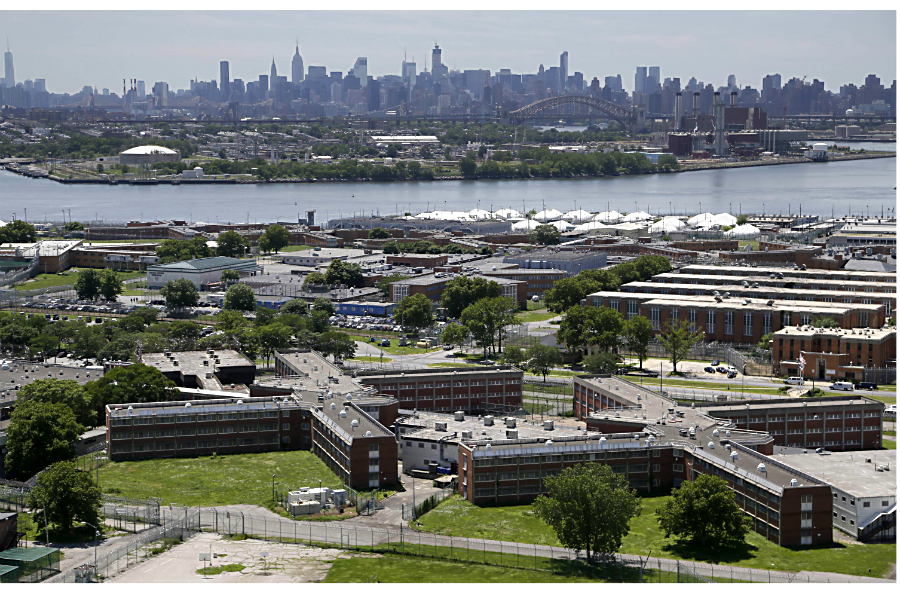

Hilda Krus is the director of the Rikers Island GreenHouse program in New York City, where prisoners nurse seedlings of herbs, tomatoes, and cauliflower. She says that the experience of caring for a garden is often therapeutic, sharing the story of an antisocial inmate she calls “B.” Before entering the gardening program, B was just as afraid of touching soil as he was of connecting with his fellow inmates.

“We gave him assignments that included raising an amaryllis bulb and making a fruit salad. The two turned out to be huge icebreakers for him,” she says.

B’s amaryllis was the first to bloom, a feat that had him on the phone with his mother reveling in his success in growing something. As far as the fruit salad goes, B not only helped make it, but later served it to the same inmates he once shunned, people he now calls friends.

“[Gardening] allowed him to practice compassion in an otherwise often harsh environment,” Krus says.

It also functions as a method of rehabilitation in what is often a deeply stressful environment.

“Inmates are sent to prison as punishment, not for punishment,” says Tonya Gushard, public information officer for the Oregon State Correctional Institution (OSCI) in Salem. The OSCI has run a garden program at its facility since 2008, when it joined Oregon’s 13 other state prisons with farm-to-table programs, where master gardeners from Oregon State University teach inmates how to grow and harvest fruits and vegetables in greenhouses.

Between 2012 and 2015, Oregon state prisoner-gardeners raised more than 600,000 pounds of produce for nearly 14,000 inmates.

Administrators often opt for the cheapest items available to feed prison populations, but instead of saving money, they’re usually spending more. Oregon taxpayers were spending almost $100 million a year on inmate healthcare costs, seven times the general fund spending on the state Education Department, The Oregonian reported in 2011. Gushard says that the potential savings for taxpayers in health costs from providing inmates with high-quality food cannot be overstated.

“It behooves us to try and keep [inmates] as healthy as possible. Not only can we keep our healthcare costs down if we have healthy individuals, but it can also save taxpayer money growing some food ourselves on-site,” says Gushard.

Farther down the coast, Wehtahnah Tucker agrees.

The nutrition offered by fresh food is important, but that’s not the end of it. “The more power people have over their well-being, the better for [themselves] and the taxpayer,” she says. Tucker heads up San Diego’s Farm and Rehabilitation Meals program (F.A.R.M.) at the Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility, which teaches about 20 inmates how to tend a garden. On three-quarters of an acre, the prisoner-gardeners spend time harvesting and sorting through ripe crops, picking what’s edible, and discarding the rest.

The produce is then served in the prison cafeteria, which, according to Tucker, is the first time in years many inmates have eaten fresh food.

Says OSCI inmate Steven Tynan, “I never really ate much fresh food growing up. [In prison] you can’t buy fresh vegetables at the canteen, so the only time we get them is when they serve lunch at the chow hall. I definitely appreciate the [prisoners] who grow them.”

Tynan, who is in the last year of a 15-year sentence, credits the man he is today to his experience eating healthy. The man whose chaotic life led him to a robbery conviction now dedicates himself to healthy life choices, from his diet to his friends, and plans to become a nutritionist after his release next October.

The programs also open doors to many who would otherwise be excluded. At the Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility, most of the prisoner-gardeners are physically disabled. Their canes and walkers would usually limit their job prospects inside the prison, but planting cabbage and uprooting weeds requires less physical exertion than most positions open to prisoners, such as cleaning bathrooms and collecting and delivering laundry.

A weekly farmers market will soon be established in the facility’s prison yard. There, inmates will be able to purchase fresh food grown by participants in the F.A.R.M. program. All proceeds will be donated to the Wounded Warrior Project, a charity that helps injured veterans readjust to civilian life.

Tucker and Gushard hail their respective farm-to-table programs as future, and necessary, models of healthcare. Instead of sourcing food from far out of state, prisons with garden programs can grow, share, and eat fresh produce of their own, reducing their carbon footprints, creating more jobs for prisoners, and improving quality of life.

• Marcus Harrison Green wrote this article for YES! Magazine. Marcus is a YES! Reporting Fellow. He is the founder of the South Seattle Emerald.