For young girls, an education; for older women, jobs

Loading...

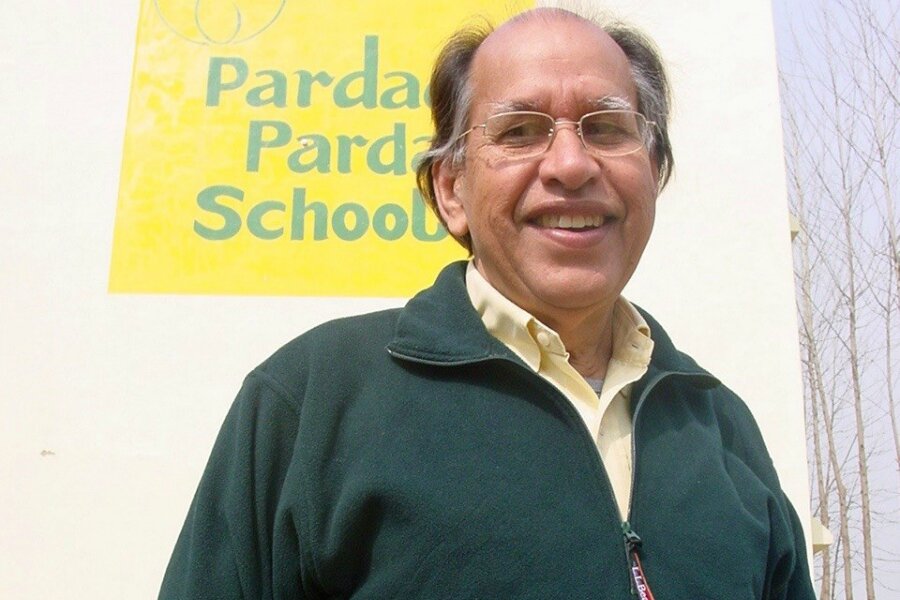

For nearly 40 years, Virendra (Sam) Singh lived in the United States, working his way up the corporate ladder to lead DuPont South Asia.

But following his retirement, he returned in 1999 to his home in the city of Anupshahar in northern India, feeling called to use the experience he gained in the private sector for another purpose.

Mr. Singh founded Pardada Pardadi Educational Society (PPES), an organization dedicated to improving the lives of women in rural India. PPES provides free education for girls and job opportunities for women, with the goal of empowering those in the poorest segments of society.

The organization aims to eliminate poverty, Singh says, by helping to produce a new generation of self-reliant, educated women with the capacity to break the cycle of poverty.

“An enlightened mother will create an enlightened family,” he says.

While Singh doesn’t point to a single moment or instance in his life that inspired him to dedicate his retirement to solving a challenging problem, he does think he learned something important in his four decades in the US.

“One of the things that I really like about America is the definition of leadership: Most of the people believe that if you are really, truly a leader, then you will not tolerate injustices around you,” he says. “If you are tolerating, if you are not doing anything about those injustices, then there must be some flaw in your leadership.”

In the minds of many India is synonymous with poverty, Singh says. Yet hose with the capacity to help seem to put up with the crushing problems confronting so many people. Reflecting on the example he would be setting for his two daughters, he came to a realization.

“I started to think – I have produced nothing at all,” he says. “Gradually I reached the conclusion: I will do something about this injustice of poverty.”

PPES focuses on women for a reason. According to the organization, as of 2011 more than one third of all Indian women were illiterate, and girls represent some 70 percent of the children not enrolled in schools. In Anupshahar, 85 percent of girls do not have access to a primary school education.

Even more devastating in rural areas is the practice of female infanticide, as well as the belief among many that girls “are nothing but a financial burden,” he says.

Seeking to reverse these statistics, and provide young women with better alternatives, PPES provides girls with a free education, during which time they also earn 10 rupees – roughly $0.20 – per day of attendance. The stipend means that upon their graduation they will have some degree of economic independence.

PPES also seeks to elevate the young women’s families as well.

“If you send your daughter to the school, we guarantee all females in the family a job,” Singh says.

Today, PPES has 1,363 girls enrolled in classes, as well as roughly 2,200 mothers and elder sisters working in various capacities through the organization, including incense manufacturing, textile production, and a call center.

Among the organization’s alumnae, 72 women now are working throughout India, 46 are in the university system, and 18 work for PPES, Singh says.

The PPES formula is simple: Those under 18 take classes, those over 18 are provided a job.

“This is the only school I know [of] that when mothers come, I don’t talk with them about what kind of math teacher I have; I take them to a textile production center,” he says.

PPES strives to be a social and economic empowerment initiative, Singh says, providing education and independence to girls and employment to older women in their families who face poverty and lack job skills and experience.

Seeing the girls and women at school and work at PPES has a powerful impact on visitors to the facility, he says. “You will be a different person” afterward, he says.

• To learn more, visit www.education4change.org.