This program in Nigeria sends children from the streets into the classroom

Loading...

| Jos, Nigeria

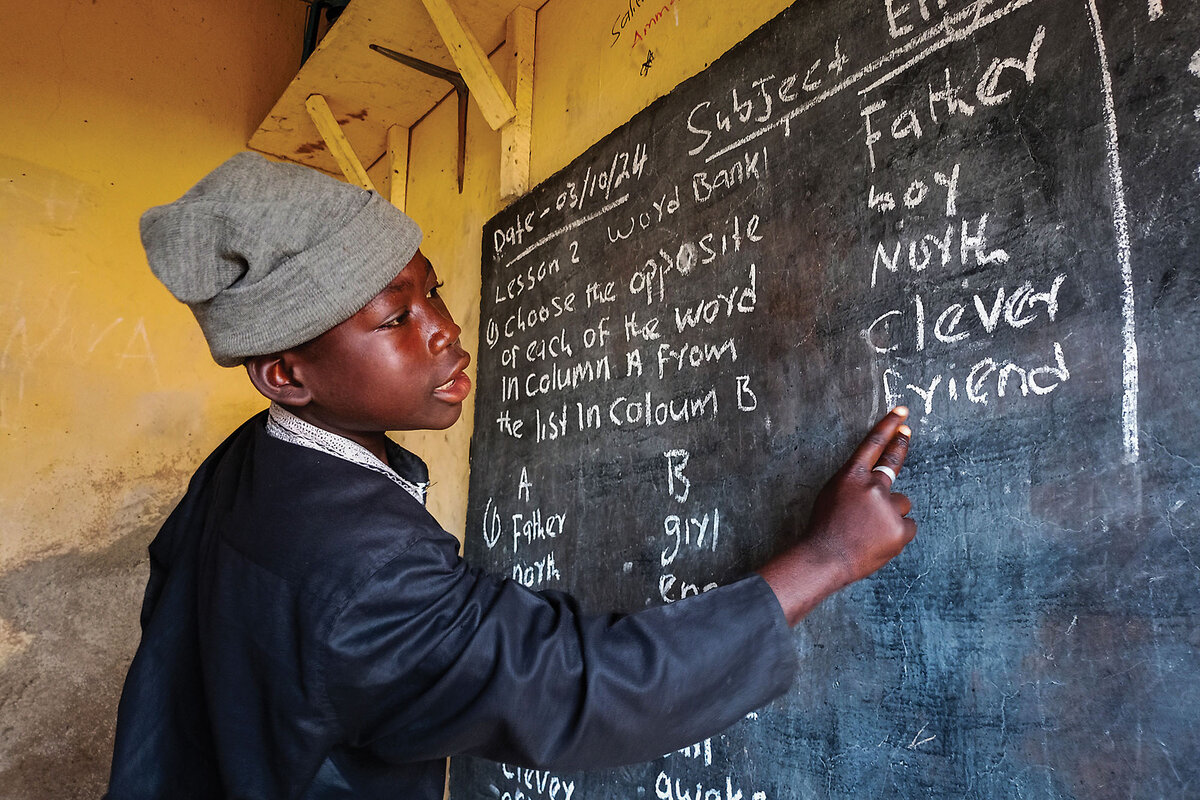

Safiyanu Mati stands at the blackboard, pointing a cane at letters of the alphabet scrawled in chalk. As he reads each letter aloud, the 25 other students in the room repeat after him in unison. When Safiyanu reaches “z,” teacher Mohammed Yahaya smiles approvingly and gestures for him to return to his seat.

“Next is parts of the body,” Mr. Yahaya announces. Immediately, the children leap to their feet, and their voices again fill the small, yellow-walled classroom.

“My head, my shoulders, my knees, my toes,” they say together in English, touching those body parts as they eagerly follow along.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onStudents of the “almajiri” system often lack access to formal schooling. One intervention program instills a love of learning and fosters self-esteem.

But this class in the northern Nigerian city of Jos is no ordinary one.

The students are children who have been sent away by their parents or guardians to study at Quranic boarding schools in what’s known as the almajiri system. Inspired by the prophet Muhammad’s migration from Mecca to Medina, the system was originally designed as a means of broadening Islamic education in precolonial Nigeria. Children traveled many kilometers from home to live under the tutelage of religious scholars, or mallams.

The system has since deteriorated, however. Today, with little government support – which was cut off during British colonial rule in favor of formal schools – many of the children don’t receive formal education beyond learning to recite from the Quran and are left to survive by begging or working menial jobs. All over northern Nigeria, these children roam the streets instead of attending classes. According to estimates cited by UNICEF, there are 10 million children in the country who are in the almajiri system, mostly boys.

“It’s not easy for them,” says Mr. Yahaya, who volunteers with the Almajiri Scholar Scheme, an education program. “This classroom is probably their only escape from how tough things are for them.”

“A fighting chance”

Growing up in the city of Kaduna, Victor Bello was disturbed by the sight of young boys in dirty clothes begging on the streets during school hours. “Sometimes I gave them my lunch money,” he recalls.

In 2022, while attending college in Jos, Mr. Bello encountered the same problem. He approached a local mallam, who allowed Mr. Bello to begin teaching the children. The program began with 30 boys per year and has since expanded to 90 boys annually.

The students, ages 4 to 18, receive lessons in reading, writing, grammar, and basic arithmetic; some also learn shoemaking and tailoring. “The goal is to give these kids a fighting chance,” Mr. Bello says. “I hope this opens doors for them.”

Bridging divides

For Mr. Bello, who is Christian, starting an educational intervention for almajiri in Angwan Rogo, a predominantly Muslim area in Jos, was no small accomplishment. Since 2001, land disputes between Christians and Muslims have led to as many as 7,000 deaths in Jos, fostering distrust and further segregation between both religious groups.

Mr. Bello explains that he first gained the community’s trust by solving a pressing issue in Angwan Rogo: access to drinking water. With the help of friends, Mr. Bello raised money for the construction of a borehole for the neighborhood. “They now know me in the community as the almajiri teacher,” says Mr. Bello, an undergraduate studying for a degree in peace and conflict resolution at National Open University of Nigeria.

He made sure that the educational program respected the boys’ Quranic studies. “I try to ensure a balance between the time we spend with them and their Quranic learning,” Mr. Bello says. Classes are held on Thursdays, and sometimes on Friday, leaving the remaining days for Quranic studies.

The Almajiri Scholar Scheme also incorporates psychosocial support as a core part of its approach, aiming to instill confidence in the children and nurture their self-esteem. One key exercise involves summoning the students to the front of the class to share their experiences from the past week. This simple activity allows them to practice public speaking in a supportive environment while reflecting on their lives.

“Many of these children have spent years on the streets, where their voices are often ignored or dismissed,” Mr. Bello says. “This exercise helps them reclaim their sense of self-worth.”

By encouraging the students to open up in front of their peers, the program fosters a sense of community and trust. It also provides an opportunity for the teachers to identify any emotional challenges the children might be facing. “For some of them, this is the first time anyone has asked how their week went, or even showed interest in their lives outside of begging,” Mr. Bello says.

Nura Abba, a teenager sent to Jos from Kano, remembers a particularly humiliating experience. Outside a restaurant where he stood begging for food, one of the people who had been eating inside the restaurant threw him a bone instead. Nura picked it up, stared at it in silence, and walked away.

When he shared the experience with Mr. Bello, the latter organized an excursion for Nura and the other boys to a fancy restaurant in town the following week.

“They said it was the first time in their lives they had eaten like governors and presidents,” says Mr. Bello, who has also taken the boys on trips to the zoo, amusement parks, and the cinema.

“The aim of this is to let them see life from the other side of the table,” he adds. “They should feel loved, cared for, and not neglected.”

“Building relationships”

The Almajiri Scholar Scheme is a praiseworthy initiative that “hits two birds with one stone,” says Jemimah Pam, founder of Gem’inate Kids Foundation, which provides education to children in underserved communities.

“We [in northern Nigeria] have some of the worst education statistics in Nigeria, and this program tackles one of the root causes,” Ms. Pam says. Only half of all school-age children in the region attend school.

Ms. Pam adds that Mr. Bello’s program is promoting trust across religious lines. “It’s not just about education; it’s about building relationships,” she says. “It ensures that these children aren’t left behind and can one day become productive members of society.”

That’s something Safiyanu and his peers in the program hope to achieve. “I want to become a teacher and help other children learn to read and count,” Safiyanu says with a shy smile.