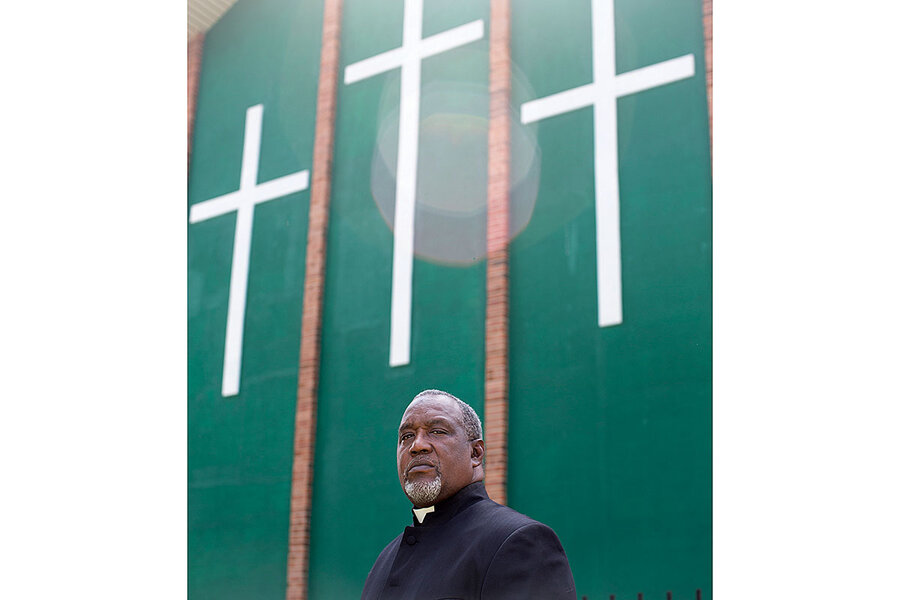

Rich in spirit: How Rev. Robin Hood fights for housing justice

Loading...

| Chicago

As he listens to Barbara Herron’s concerns about her home, the Rev. Robin Hood is sympathetic and reassuring. The city of Chicago has been telling her she needs a back porch, she says, and she may have to go to court. Mr. Hood, sitting in her dark living room, gives her a number to call. The city has promised not to mess with the homeowners who were victims of a predatory mortgage fraud, he tells her.

Two years ago, Ms. Herron almost lost her home completely. Her mother, who had dementia, had signed reverse-mortgage papers believing she was getting home improvements. After her mother died, Ms. Herron was told she owed $80,000 on a loan that neither she nor her mother had ever received. The home was foreclosed, and her eviction was scheduled for the day after Christmas.

Mr. Hood, who called in a news team as nearly 60 years’ worth of belongings were packed to go out the door, helped ensure that didn’t happen. But Ms. Herron, who lives with her great-nephew, still worries. “We’re still fighting it,” says Ms. Herron, who has lived in the house since she was 11.

Why We Wrote This

Seeking help is hard if you mistrust the helper. As a housing scam rocks his neighborhood, a Chicago minister has managed to broker that trust between the community and legal help.

When Mr. Hood talks about the scam that almost cost Ms. Herron and so many other North Lawndale residents – almost all older African American women – their homes, he’s filled with anger. Some $10 million in equity was taken out of his community, one of the poorest in Chicago, affecting around 125 homeowners.

But he’s committed to keep fighting. For several years, Mr. Hood has been a uniting force bringing together federal prosecutors, pro bono lawyers from Northwestern University’s Bluhm Legal Clinic, and victims who were wary of trusting anyone. He’s used any tools he can muster to help homeowners – community meetings, media connections, law enforcement partnerships. His work on the mortgage scam has complemented his anti-violence work in the neighborhood.

“Stuff like this is so hugely connected and important,” says the Baptist minister. He lists what’s needed to get on top of endemic violence: “Stabilized home, stabilized community, stabilized schools.”

Home as legacy

With his austere black clerical suit and graying beard, Mr. Hood is a larger-than-life figure in this community. His phone rings regularly with calls from people needing help, connections, or advice. His conversation is peppered with anecdotes about everything from local gang leaders and gang wars to Martin Luther King Jr. This neighborhood on Chicago’s West Side has history, and a reputation. King moved here in 1966. It’s also the birthplace of the Vice Lords, one of the oldest Chicago gangs. More than 40% of households live below the poverty line, and there have been at least 20 homicides so far this year. But the violence caused by the reverse-mortgage fraud was of a different sort.

Mark Diamond, who is facing federal charges, allegedly targeted older homeowners, many of them with disabilities, and convinced them to sign over equity in their homes to him. He is accused of promising home improvements that were never delivered. Mr. Diamond’s lawyer did not respond to a request for comment.

Mr. Hood’s own aunt lost around $175,000 in the scheme. “These [homeowners] are the people who are stabilizing the neighborhood,” says Sam Tenenbaum, director of the Complex Civil Litigation and Investor Protection Center at the Bluhm Legal Clinic. Mr. Tenenbaum has been fighting many of the eviction and foreclosure cases that resulted from the scam. “For all these people, this was their only real investment; they viewed it as a legacy,” he says.

Mr. Hood says he first learned about the scams around five years ago, when a couple of young men he knew in the community were threatening to go after Mr. Diamond with guns. One of their grandmothers had apparently signed a reverse mortgage for more than $200,000 to the businessman. “The woman thought she was getting a free government program, and when she got the letter [saying she owed money to lenders], she had a massive heart attack and died,” one young man told Mr. Hood. He talked the young man down and promised to find a legal way to go after Mr. Diamond and his partners.

Growing up in North Lawndale, Mr. Hood hated his unusual name. It wasn’t until he turned 40 that he asked his father why he gave it to him. “You’ll be Robin Hood for real. You’ll rob from the rich and give to the poor,” the minister remembers being told. Now, as he works to get restitution money for the mortgage fraud victims, “I tell people, ‘Be careful what you name your child,’” he laughs.

His ‘Jonah moment’

Mr. Hood for years has worked to connect his ministry directly to the community he lives in, working to fight violence and promote mentorship and jobs for youth. But at one point, the violence became too much even for him. His brother, sister, uncle, and two cousins had been killed in North Lawndale; he and his family moved to Florida for two years. He calls it a “Jonah moment,” referring to the Bible story in which Jonah flees rather than preach.

But when he returned to Chicago, he had lost some of his connection with the community. The mortgage fraud crisis in some ways provided a reentry point. Fighting for justice, in this case, has required outside help. This is a neighborhood that is distrustful of institutions – police, federal agents, universities – often with good reason, says Mr. Hood. Working to shut down fraud and protect affected homeowners has called for strong partnerships. “It’s difficult to get trust after they’ve been cheated,” says Mr. Tenenbaum of the law clinic. “In some cases where there was resistance, [Mr. Hood would] go and speak with the family and let them know they could trust us. He’s really been tireless in what he’s done.”

Mr. Hood has held community events both to connect victims to help and educate them about reverse mortgages. The cases aren’t all resolved, and the Northwestern lawyers are still fighting on behalf of the homeowners. But so far, they’ve managed to keep all their clients – some 35 victims – from being evicted. Recently, they helped get a $10 million fund set aside for homeowners, including fraud victims who have been evicted, in the bankruptcy settlement of Reverse Mortgage Solutions, one of the lenders in the Diamond scheme.

In the case of Ms. Herron, Mr. Hood says her near-eviction also gave him an opportunity to address gang violence. Her great-nephew had been in juvenile detention. When Mr. Hood helped her avoid eviction, he also got the nephew, a former gang leader, released, but with the promise that he return to school and get a job.

Mr. Hood notes how the community’s escalating violence and housing insecurity are connected. “When you got 120 people in the same neighborhood with the same issues, that’s a destabilizer in the community,” he says. He still gets discouraged every time there’s a shooting, but the steps forward keep him going. Most recently, he succeeded in getting the state to promise 375 youth jobs to the neighborhood. When asked what’s important to know about North Lawndale, he cites the challenges. But ultimately, he concludes, “this community is a community of love.”