In Pakistan, she sees the value in children who ‘are never seen or heard’

Loading...

| Islamabad, Pakistan

On the outskirts of Islamabad, Pakistan, there is a neighborhood a world away from the luxury cars, private schools, and orderly streets in the capital. Here, around a Sufi shrine called Bari Imam, mud-brick houses line the dirt roads, little boys with dirty faces offer to wash cars for less than a dollar, and girls in torn dupattas, long scarves, try to sell flowers to people who come to pray at the shrine.

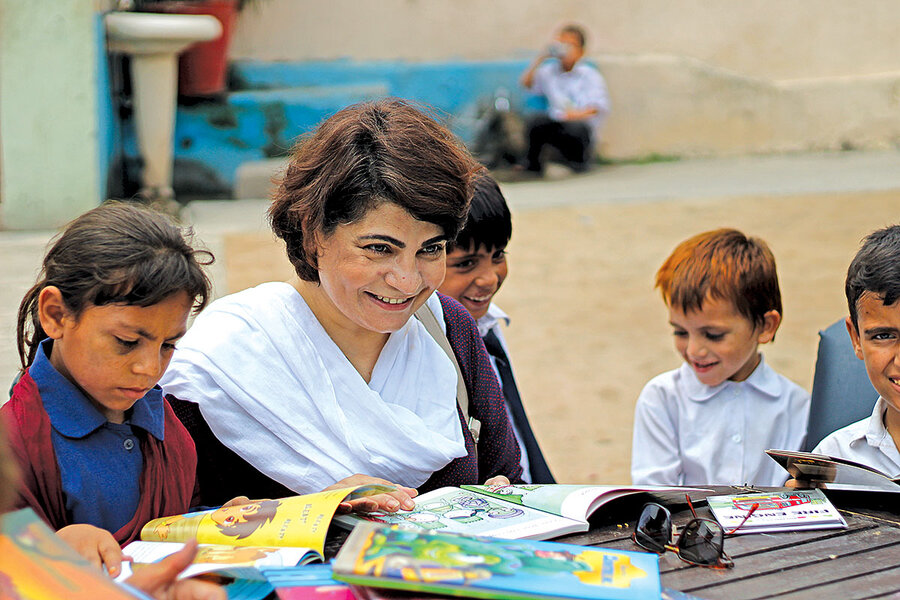

But not far from the shrine is a school that provides education and solace to these street children, who otherwise would face abuse by gangs that operate in the area. Zeba Husain, the founder of Mashal School, is greeted enthusiastically by the students as she walks in the gates with a smile. There is a never-ending flow of people to her office – mothers, volunteers from the country’s top colleges, and private donors with their checkbooks.

Ms. Husain is clearly loved in the community. And yet her life has been an uphill struggle. Getting her initiative to where it is today – with close to 1,000 students, four branches around the capital, and 790 former students mainstreamed into the government school system – has not been easy. “I started with just two children 10 years ago,” says Husain, who is in her 50s now.

Why We Wrote This

Plenty of people are doing good work in Pakistan, but too often such stories don't reach Western readers. So here’s one person helping street children – something that’s needed elsewhere, too.

What spurred her to dedicate her life to these children were her own experiences in her youth. She says that as a child, she encountered sexual advances by mullahs in madrassas: “They would try to touch me.” She says she also experienced racism during a short stay in London in the 1970s.

“Feeling harassed and feeling uncomfortable was something that was truly embedded in my feelings. I could feel that a person needs to be free of these things, of exploitation,” she says.

But it was working with refugees as part of United Nations operations in Pakistan that really gave her a sense of what some people have to go through. “That was something that changed my life because I had never seen that aspect of humanity, the human suffering,” she says.

“Some of us just get trapped. I’ve seen so many [people] just taking their own lives because of the hopelessness that they have created in themselves,” she adds.

This hopelessness is something that Husain could see in the eyes of the street children at Bari Imam when she first came across them 10 years ago. She had come to the area to go hiking up the lush Margalla Hills that surround Islamabad. “[There], I saw these children,” she says. “I asked them, ‘Don’t you go to school?,’ and they said, ‘Nobody keeps us; nobody wants us.’ ”

Husain had returned to Pakistan from the United States, where she had moved with her parents and children after a difficult divorce. But her father’s sudden death persuaded her to accompany her mother back to Pakistan. It was around this time that she found out she had a brain tumor.

“I cried a lot,” she says. “But then I had a dream which made me realize there is a reason for this, that my life is only starting now.” The tumor was diagnosed as benign, but she knew it was time to act on her longtime dream of helping poor people.

The school at first

So Husain told the children that she would start teaching them. But the task ended up being more complicated than she expected, with the children first needing attention for some health issues.

Slowly, she started teaching them arts and sports. “I didn’t start from regimented things because of the regiment they’ve had in their lives of every day going out to fend for themselves. They needed a change,” she says.

As the school gradually grew, the women in the community also became interested.

“It was very, very encouraging that the mothers would come in, not the fathers, because the mothers have gone through a lot with the fathers,” says Husain, referring to the fact that some men have used drugs and behaved violently.

She decided to start providing the women with skills development. “They could see their future in these children’s eyes,” she says.

The school day was arranged so the children would still have their afternoons free for work. Otherwise, persuading the families to allow the children to come would have been difficult. And the curriculum was tailor-made to suit the needs of the children. Husain added subjects like nutrition and hygiene – topics that most other Pakistani children learn about at home.

Also, many students had behavioral issues. “There was a lot of bullying, stealing, pinching, biting, and sexual abuse in the classrooms. We had to gradually work with that first and then bring in education,” Husain says.

Most of the children had been sexually abused on the streets. According to Husain, men in the area often lure children with the promise of money. Because of poverty, parents expect their children to work, no matter how young or vulnerable they are.

At Mashal School, Husain hopes to break these patterns and get the children to realize what their interests and passions are.

“These children are never seen or heard,” she says. “With time and socialization I have seen a lot of change.”

The school made it easier for the children to look out for each other on the streets. But the local people, especially members of criminal gangs, were not happy about this.

They started throwing cow dung at her school, Husain says, and there was even a shooting incident. “I said if I have to be shot down for this work then let it be, because I would rather die for a cause than [die for no special reason]. So they realized this woman is not standing down,” she says. Since then, she has not been bothered.

Students’ desire to help others

Many of her students have now completed their education, and some are working at restaurants as waiters. “In the past, they were picking up garbage,” Husain says. “And the beauty of it is that they all want to do something for others.”

Owais, age 12, is one student who has developed a desire to help others. He is disabled; he had a leg and hand amputated after an accident at his house. “I want to be a doctor when I grow up,” he says. “I want to help people who are like me.”

According to Husain, Owais was “shattered” when he first came to the school. But his confidence has grown, and he dreams of riding a bicycle despite his disability.

Sahil, a Pakistani nongovernmental organization that is working to combat child sexual abuse in the country, has collaborated with Mashal School on teacher training. Its staff members have witnessed the change in the children.

“Zeba Husain is doing excellent work in a marginalized society where there is no source of quality education,” says Atiq ur Rehman of Sahil. “In such circumstances, it is a great challenge for Ms. Zeba to convince the families to send their children to school. She even managed [to enroll] special [needs children], orphans, and overage children.”

But Husain says that her tumor has come back, and she is constantly on medication. She foresees herself continuing for another five years and then, ideally, handing the project over to someone else.

“Making a difference for a little time goes a long way because it restores your confidence in humanity,” she says.

“But this is my lifeline,” she continues. “It’s helping me to live as well. I’m doing something which is helping others, and it’s giving me life and healing me.”

• For more, visit mashalschool.org.

Three other groups supporting education

UniversalGiving helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations around the world. All the projects below are vetted by UniversalGiving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause.

• Hagar USA is committed to restoring wholeness to the lives of women and youths who have endured human rights abuses. Take action: Help provide education access for Cambodian human rights abuse survivors.

• Warren Majengo Foundation gives stability and security to children in Tanzania who have nowhere else to turn. Take action: Financially support the basic needs and education program at this organization’s orphanage.

• Helen Keller International aids children who are struggling in the classroom because they can’t see the board. Take action: Donate to the ChildSight program to facilitate learning.