His mission to fix leaky taps has saved millions of gallons of water

Loading...

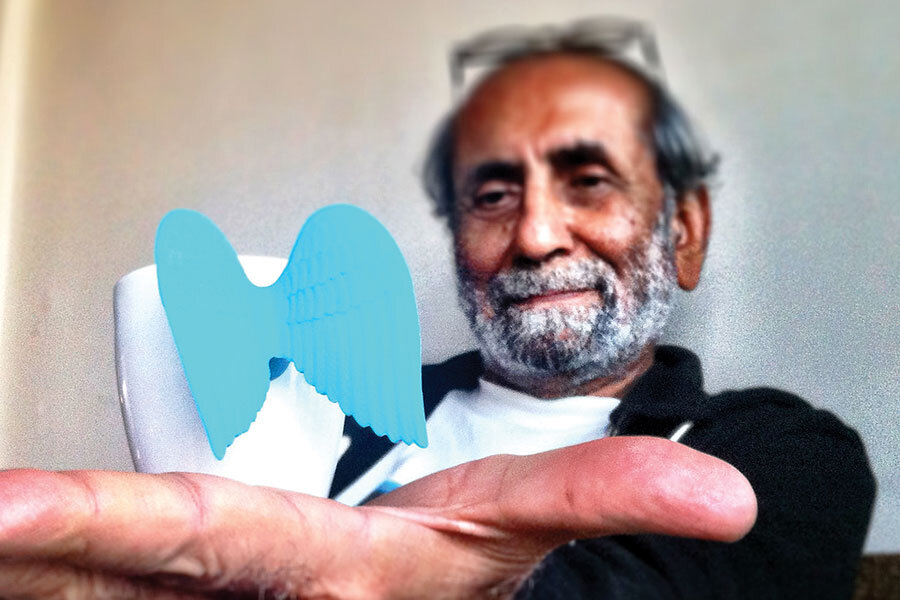

| Pune, India

Many words have been used to describe Aabid Surti over the years. Writer, artist, cartoonist. Humble, soft-spoken, energetic. But few would have expected conservationist or environmentalist to be added to the list. Especially not when Mr. Surti was in his 70s. But the Drop Dead Foundation (DDF), a nonprofit run by him, has in the past nine years managed to save millions of gallons of water in the Mira Road-Bhayander suburbs of Mumbai. How? By fixing leaky taps.

Always one to break the mold, be it as a cartoonist or writer, Surti has long experimented with new ideas. As a painter he created a rage by developing a technique called mirror collage. At the peak of the bandit menace in India, he created Bahadur – a character who protected citizens against bandits – for his comic strip “Dabbuji.” Bahadur was accompanied by Bela, with whom he had a live-in relationship – and this was in the 1980s, when such concepts were taboo in India. Now, Surti has found a creative way to change the mind-set of many toward water conservation.

Since 2007, Surti has visited approximately 13,000 homes and fixed nearly 3,500 taps.

Surti’s mother, a widow, migrated to Mumbai from the Indian city of Surat in 1943. Surti, his mother, and his brother shared a room with 15 others, and his mother worked as a maid to send her sons to school. Surti remembers standing in line at public taps, before dawn, to catch the day’s share of water. That memory never left him. As an adult, he was irked by the sight of a dripping tap in the homes of friends or relatives, and he often tried to persuade others to get their taps repaired.

Leaky taps in India are ignored in most middle-class homes because hiring a plumber is expensive – 200 to 500 times the cost of the faulty washer that needs replacing. When friends pointed this out, Surti found he had no response.

But in early 2007, he came across a statistic that said 1,000 liters of water (265 gallons) are wasted every month by a dripping tap. Reading that, Surti knew he had a valid reason to ask people to fix their taps.

“I always had this picture in my head of people dying due to the lack of water, and water dying because it was being wasted. And that is how Drop Dead Foundation came about,” says Surti.

Surti began by hiring a plumber and visiting the homes of family members and friends. Then he started to take the plumber to nearby residential buildings and have him repair the taps free of charge.

With time, DDF has developed a more structured process. Currently, on Monday mornings a DDF volunteer visits buildings in the area and explains DDF’s work to the secretaries who manage these housing societies (which are similar to condominium associations). Those who are interested in the foundation’s services then display DDF posters somewhere prominently visible to residents. On Saturday, the volunteer asks the secretaries to distribute pamphlets explaining DDF’s work to the residents. Finally on Sunday, Surti, the volunteer, and the plumber visit homes to check and repair the taps.

‘God becomes your fundraiser’

Though Surti is the author of some 80 books, as well as a skilled painter and cartoonist, his morals never let him exploit his creative skills for monetary gain. So when the idea of visiting buildings first arose, he was also confronted with the issue of cost. As he was mulling this over, he learned that he had won a lifetime achievement award for his writing – the Hindi Sahitya Sansthan Award, with a cash prize of 100,000 rupees ($1,500). “I have always seen that when you choose to do something selflessly, God becomes your fundraiser and the universe helps you. And it has so happened that whenever I was low on money, I either received more cash awards or found a willing genuine donor,” says Surti, who spoke in a phone interview.

The printer he first hired to produce the pamphlets refused to charge him. The plumber he first hired refused to charge him. And so it has continued with others. Says Kailash Kumar, the plumber who works with him now: “I feel good doing this. It is a matter of two to three hours, once a week. Why should I charge? He made me realize that anyone can work to better society.”

That sentiment is echoed by a couple who currently volunteer with Surti. He visited their community one Sunday – an experience that moved them deeply. “Sunday is when people rest, but it is that day when Mr. Surti works. At his age, he could have just relaxed, but he is so self-motivated and dedicated that his energy is infectious,” says Manish Modi, who visits housing societies to sign them on. His wife, Rajeshwari Modi, who accompanies him on weekends, adds, “What he does cannot be more pertinent. The locality we live in gets water once in three days and that, too, for 15 minutes. Even if four to five people understand what he is doing, then it is worth the time and effort we are all putting in.”

Rajesh Diwan is secretary of the Akanksha Co-operative Housing Society in Mira Road, which invited DDF to visit after a poster was spotted in a neighboring community. “I am 37 and have never thought about social responsibility, while Mr. Surti has been doing this for years. His thought process is superior to most,” Mr. Diwan says.

India, and in particular the state of Maharashtra, which includes Mumbai, has seen drought the past two years. Given that, Surti’s work has found much public appreciation. In fact, he has received national and international media recognition the likes of which he did not receive his entire artistic career.

“He has always been extremely determined and has the ability to work around a problem,” says Aalif Surti, one of Surti’s sons, who wrote a blog post about DDF that went viral.

‘Easy and replicable’

Surti encourages replication of the DDF system, and he’s put up materials, including posters and pamphlets, on the DDF website for others to download and use. “I do not even care if people don’t use the name Drop Dead. Make your own one up. But the idea is to keep this easy and replicable,” he says.

This gesture has found a willing audience. Archana Singh, an associate professor at Kamla Nehru Institute in Sultanpur, India, connected with Surti via Facebook in 2010. She was a fan of his creative work, and then she found out about DDF. She invited Surti to her college to address the students last year. The outcome of his address was Water Warriors, a student organization fashioned after DDF, which fixes leaky taps in Sultanpur.

“His philosophy was to use whatever he had already created for the benefit of others. He is uncaring about getting credit for his work, but my life has undeniably been enriched because he fine-tuned my social dimension,” Dr. Singh says.

Surti insists his goal is simply to help people realize that it doesn’t take much to give back. “I could have taken money which was offered to me, set up an office, and run a full-fledged business or [nongovernmental organization],” he says. “But the intent was always transparency and to show people that anyone can make a difference. All it takes is [a few hours of my week], and the impact has been immeasurable.”

Few households that Surti visits even get to know him. He usually sends a female volunteer and the plumber inside while he sits outside. “But once a man invited me in and kept insisting that I tell him the reason why I am doing this,” he says. “I told him this was my prayer: Choose your prayer; whatever form suits you, pray.” And that, perhaps, is the biggest lesson from Surti’s actions: Do something, anything, but ensure that you give back. Choose your prayer.

How to take action

UniversalGiving helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations around the world. All the projects are vetted by UniversalGiving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause. Below are links to groups supporting sustainability:

Water Engineers for the Americas lends hydro-engineering expertise so Latin American communities have sustainable potable water systems and sanitation. Take action: Contribute to funds for rebuilding a water system in Yajalón, Mexico.

Globe Aware promotes sustainability and cultural awareness. Take action: Volunteer at a Chinese middle school.

Give a Day Global connects international travelers with daylong volunteer opportunities. In one example, participants work at an organic farming cooperative outside Havana and learn about sustainable farming. Take action: Sponsor a volunteer.