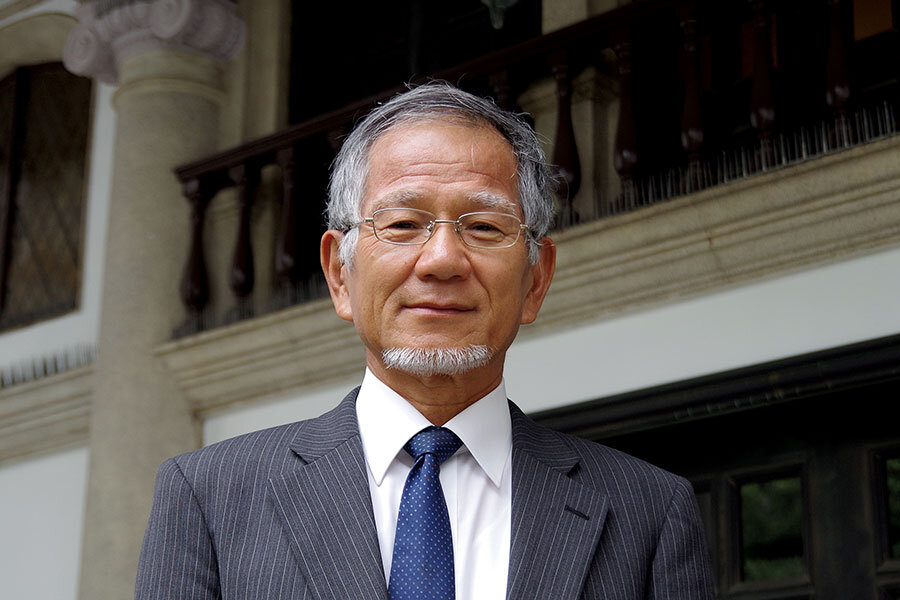

Terumasa Akio saw poverty firsthand. Now his charity helps 400,000 children.

Loading...

Terumasa Akio vividly recalls the idyllic setting, innocent children, and grinding poverty of a rural Thai village he visited more than a quarter-century ago.

By 1987, Mr. Akio had traveled widely abroad. Still he was astonished at the economic disparity between that village in northeastern Thailand and the Thai capital, Bangkok.

“There were no wells and no electricity in the village,” and almost no children attended school past the elementary level, says Akio, now chairman and founder of the Education for Development Foundation International (EDF-International), which includes the Minsai Center in Tokyo.

Since 1987 the Bangkok-based charity has helped provide educational opportunities for nearly 400,000 disadvantaged children in Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Myanmar (Burma), and Cambodia.

In the 1980s, a Thai student from that village had been studying in Japan, and he wanted Akio to see his homeland. They had come to know each other through a home-stay program that Akio had established on the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido.

During Akio’s stay in the Thai village, a mother came to meet with the Thai student, imploring him for help to send her daughter to junior high school. The child had excelled in her studies.

The student did what he could to help. Akio also wanted to do something: He collected 410,000 yen ($2,800 at that time) from 41 people (10,000 yen each) in Japan to enable 41 children in the Thai village to attend junior high school.

Some of the donors later contacted Akio to ask whether the money had truly been used for Thai children. So Akio decided to go back to the village to make sure of it. He learned that the donations had indeed been spent on the children’s education.

But when Akio met with some of the students who had received help, he recalls, they began pleading tearfully with him to help their friends who could not go to school and would have to go to a big city to work because they needed to support their families.

After returning to Japan, Akio stepped up his fundraising. This time he was able to gather enough money for 600 children to attend school. “I felt ... a strong sense of responsibility” to raise a larger amount, recalls the soft-spoken man with a trimmed gray goatee.

Then Akio was confronted with something unexpected: Few children in that region of northeastern Thailand, called Isan, showed much interest in going to junior high school. Akio wondered why.

He learned that the children felt loyal to their parents. “They did not think they could do their filial duty if they went to junior high school,” he says. “So, I told them, ‘If you go to junior high school, you would be able to give more help to your parents and contribute to your community as well.’

“Then, they raised their hand all together, speaking out loud, ‘I want to go to junior high,’ ” he recalls with a flashing smile.

In the third year, donations increased 10-fold: EDF-International was able to send about 6,000 children to junior high school.

The charity has also helped build schools, found libraries, provide educational materials, and offer health education and teacher-training programs. And EDF-International promotes technical and vocational training programs that teach job skills in rural areas, Akio says.

Some of its schools serve as adult learning centers as well. There, residents can gain knowledge and skills in such areas as aquafarming and organic agriculture, Akio says.

From the beginning, Akio had a strong desire to help people far from the big cities in outlying provinces.

“Instead of working in urban slums, we operate in rural areas [in five countries] with a focus on human resources development so that locals” will stay and contribute to improving their communities and not migrate to urban slums, he says.

“As we are a small NGO, we cannot help bring about a revolution at one time,” Akio concedes. “But we first set a precedent in which changes can be introduced. Then, we accelerate our efforts to create 20 to 30 more cases like that, which will lead to a transformation. We believe that will help achieve a revolution 10 years later.”

Before his deep involvement in this charitable work, Akio had established the Hokkaido International Foundation exchange program in 1978 to boost international exchange activities on that Japanese island. In the 1980s, he founded Exchange:Japan to promote Japanese language education at universities in Canada and the United States. He helped set up a class at about 150 of them.

Akio is quite an athlete, too: He rides his bicycle between his home and office every day, a 19-mile round trip, and he began participating in triathlons at age 64. “Mr. Akio is very active and likes running a marathon,” says Natsue Yamamoto, a longtime EDF supporter. “He always has a boyish grin. Yet, he has a very strong belief in his work.”

Ms. Yamamoto recalls when Akio and a handful of EDF-International staff members were working out of a tiny office in a shared office building in 1996. Yamamoto, a resident of Hokkaido, has supported children in Thailand, Myanmar, and Laos through EDF-International for about two decades.

In 1995, she took time off from work to travel to Thailand to meet with a student she had helped for three years. Today she values EDF-International’s transparency. “We know who has received donations,” she says.

Takao Akaishi, an associate professor at the school of medicine at Niigata University, has been involved in EDF-International activities for a quarter of a century. After visiting Southeast Asia, Dr. Akaishi felt he wanted to do something to help, he says. He supports EDF-International because Akio “established a solid base for his activities and understood local situations,” Akaishi says. “I have faith in him.”

About 97 percent of donations that EDF-International’s Japan office receives come from individual donors across Japan, such as Yamamoto and Akaishi, the charity says.

Meanwhile, the Thai children have also given something back to Japan. When Japan was struck by a devastating earthquake and tsunami in 2011, the Thai students raised funds to donate to disaster-stricken regions through EDF-International in Bangkok.

Akio felt so grateful that he drove to Rikuzentakata, one of the hardest-hit cities some 250 miles north of Tokyo, and brought the contribution to a junior high school there that had supported Thai children through EDF-International, he says.

Akio highly values such private efforts to solve humanitarian problems.

“Individual initiatives are more efficient than government moves,” he says.

• To learn more about EDF-International, visit www.edf-international.org.

How to take action

Universal Giving helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations around the world. All the projects are vetted by Universal Giving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause. Below are groups selected by Universal Giving that help children in Southeast Asia:

• Globe Aware promotes cultural awareness and learning about cultures without trying to change them. Take action: Volunteer at a school in Cambodia.

• Christian Care Foundation for Children with Disabilities serves children with disabilities in Thailand so that they can develop their full potential and integrate into society. Take action: Pay for a year of education for a child in Thailand.

• Greenheart Travel is a nonprofit international exchange organization providing cultural immersion programs. Take action: Volunteer to teach children in Vietnam.