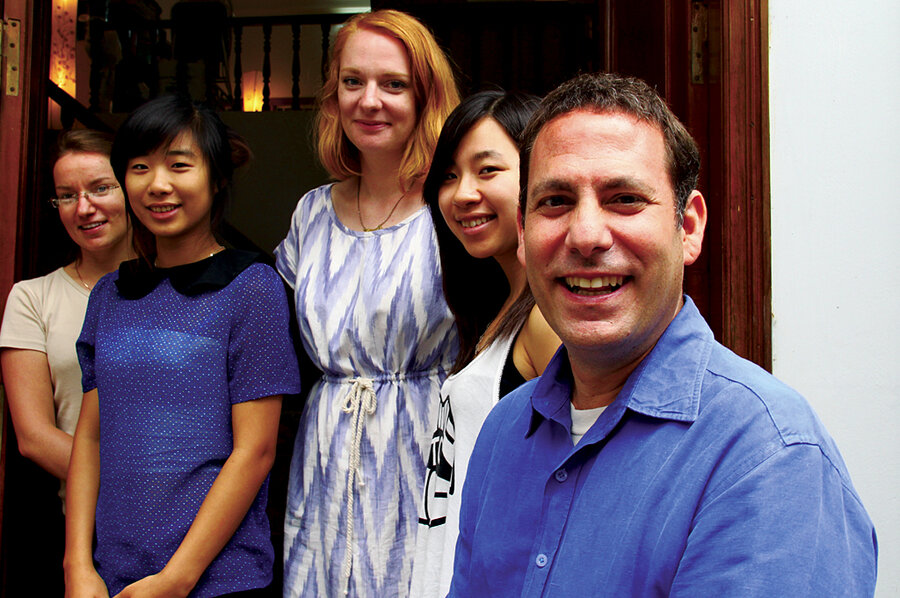

Bruce Lasky trains young lawyers in Asia to defend the poor and powerless

Loading...

| Hanoi, Vietnam

Bruce Lasky distinctly remembers the advice he once received from a colleague in a Florida public defender's office. "We're lawyers," the colleague said. "Not social workers."

But Mr. Lasky, then fresh out of law school, didn't agree. He saw the legal system as a tool for empowering the disadvantaged. In Florida he spent nine years representing low-income adults and juveniles charged with offenses ranging from drug possession to theft and murder.

And for the past 13 years, the New York City native has quietly championed legal reform in Southeast Asia, a region where poverty is widespread, the rule of law is often weak, and governments are criticized for alleged violations of human rights.

Bridges Across Borders Southeast Asia Community Legal Education Initiative (BABSEA CLE), a nonprofit Lasky cofounded about a decade ago, trains young lawyers across the Asia-Pacific region to defend the powerless, even though law schools here typically place little emphasis on helping vulnerable groups.

Lasky's organization has worked with more than 40 universities in nine Asia-Pacific countries to develop programs that teach lawyers to understand the need to provide legal services to at-risk communities – a process lawyers call "clinical legal education," or CLE.

Le Thi Chau, deputy head of the law department at Vietnam Trade Union University in Hanoi, says students in her law program all receive CLE thanks to the university's links to BABSEA CLE and the United Nations Development Program. The law program has not received any support from the Vietnamese government, she adds, but it has improved the university's law curriculum and led directly to young lawyers doing community outreach in three provinces.

"The program is very effective," Ms. Chau says.

Poor people across Southeast Asia face discrimination and inequality. And Vietnam and other countries have outdated legal systems, in many cases introduced by colonizing powers.

"BABSEA CLE is the pioneer of CLE in this part of Asia," says Nicholas Booth, a Hanoi-based policy adviser and legal specialist at the United Nations Development Program, a BABSEA CLE supporter. "The fact that they do so much with such a small team ... is also for me a remarkable and refreshing thing in a world of huge donors and huge implementing project organizations."

The communist governments of Vietnam and China, in particular, are known for their harsh treatment of people who directly challenge their one-party rule. So Lasky takes an intentionally "neutral" approach to promoting social justice in the region in order to avoid attracting unwanted attention, he says.

BABSEA CLE did receive a $60,000 grant from the New York-based Open Society Foundations, a group that promotes democracy and human rights in developing countries. But Lasky says his organization has declined offers of support from other donors with explicit human rights agendas.

Instead, Lasky says he prefers to work within the existing power structures to train a broad swath of law students, including those who plan to work as corporate lawyers or government officials.

"We don't tell people, 'Look, you have to be a social justice missionary.' We tell them, 'Go out and make money, but just keep giving back,' " Lasky says in Hanoi, where his organization has an office. "That makes us more stomachable because we're not looked at as if we're brainwashing people."

Lasky's organization has grown partly thanks to his infectious charisma, but also because it doesn't follow a one-size-fits-all model, says Lisa Radtke Bliss, a law professor at Georgia State University who spent her summer volunteer teaching at a university in Thailand affiliated with BABSEA CLE.

"They're not tied to one country or school," Ms. Bliss says. "They can tailor programming to meet needs on a local basis."

A few years ago, when funding was particularly tight, Lasky mortgaged his Florida home and put about $80,000 on his credit card to keep BABSEA CLE alive. Funding is still a "hodgepodge," he adds. The nonprofit raises its $400,000 to $500,000 annual budget partly by organizing half-marathon races.

But BABSEA CLE is growing, and Lasky continues to shuttle around the region lobbying law schools to adjust their curricula to emphasize social justice. The results are beginning to show, he says, as program graduates enter the workforce and put their values into practice. Some work for nonprofits, others in private law firms or local governments. One graduate works for Cambodia's department of corrections.

Lasky also has received invitations to help develop CLE programs in the Middle East. "We don't want to be limited by borders," he says. "Bridges is in our name, and we're all about bridging and facilitating."

• To learn more, visit http://babseacle.org.

Where help is needed: how you can help

UniversalGiving (www.universalgiving.org) helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations worldwide. Projects are vetted by UniversalGiving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause.

Here are three opportunities, selected by UniversalGiving, to donate or volunteer:

• Asia America Initiative (AAI) builds peace, social justice, and economic development in impoverished Asian countries plagued by terrorism, religious conflict, and severe poverty. Project: Adopt a school.

• Globe Aware promotes cultural awareness and sustainability through short-term volunteer programs around the world. Globe Aware’s projects and solutions seek to help others obtain a happy, healthy, and independent life. Project: Volunteer to make a difference in Cambodia.

• Cultural Canvas Thailand. The mission of Cultural Canvas Thailand is to generate awareness and volunteer support of the current social issues facing Chiang Mai, Thailand, through the promotion of equality, community interaction, and social change. Project: Volunteer with Burmese migrant learners.

• Sign up to receive a weekly selection of practical and inspiring Change Agent articles by clicking here.