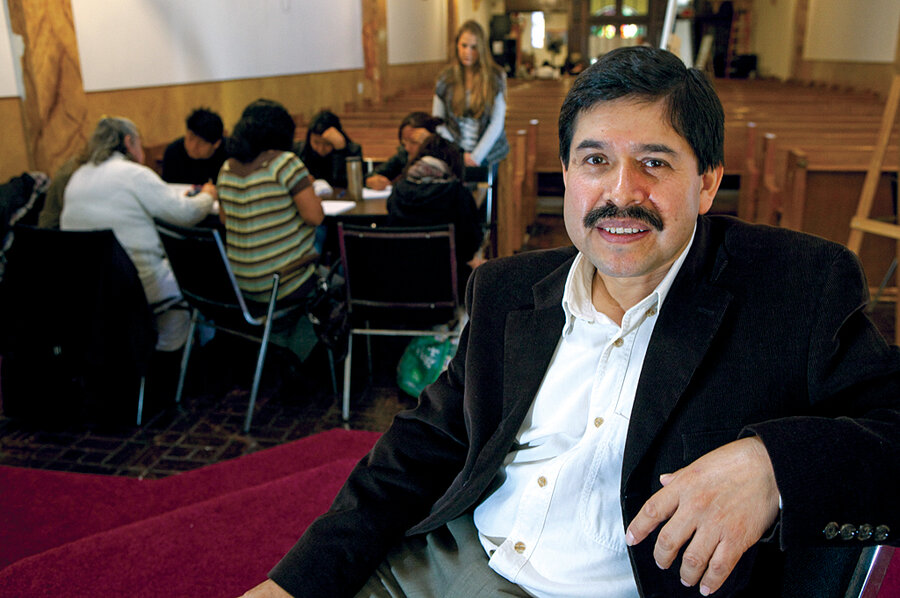

Juan Castillo teaches immigrants who speak obscure languages how to make it in New York.

Loading...

| New York

All of Juan Castillo's adult students have had little or no formal education. But that isn't always the main impediment to them tackling their classes, taught in Spanish or English.

It's the fact that they don't speak either of these languages.

Many of Mr. Castillo's approximately 400-plus students do come from Latin America – Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Ecuador. But they are from indigenous communities where idiomas de la tierra, local native languages, are spoken.

QUIZ: Could you pass a US citizenship test?

Ethnic communities like the Mixtecos, from southwestern Mexico, often live isolated lives in New York. Those who cannot speak Spanish avoid shopping trips or other ventures around the city, and routinely refuse invitations from Hispanic social organizations to attend meetings.

"It's hard to approach them and difficult, even for us, to get into these communities," says Gabriel Rincon, president of the Mixteca organization, which provides health and educational services to Hispanic immigrants in Brooklyn. "It's a major problem.... There's an element of fear that exists."

At El Centro del Inmigrante, or Center for Immigrants, in Staten Island, about a third of the adult students identify as indigenous. "There's always a hesitancy for them to go into any type of organization if they are not proficient in Spanish," explains Gonzalo Mercado, El Centro's executive director. "They feel very vulnerable.... They might all be indigenous, but they are from very different parts of Latin America and speak different dialects."

Nearly 20,000 Mexican nationals in the New York metropolitan area come from indigenous communities and consider a local dialect to be their first language, according to the Mexican Consulate in New York.

Castillo, from Veracruz, Mexico, where he worked as a civil engineer, has earned the trust of many undocumented, indigenous people in New York. Now a construction worker who recruits his students through church connections, Castillo isn't entirely sure why he has their confidence.

"Why do they trust me?" considers Castillo outside a Sunday morning literacy and math class at a Staten Island church. "I've been doing this for 17 years. They know I won't hurt them."

Castillo launched his first basic skills class in Harlem in 1995, when he noticed that some Mixtecos he knew were being exploited in their construction jobs. Their lack of immigration documents places them in precarious positions on the job, Castillo says. They are often frightened to confront their bosses about a problem such as unpaid wages.

Castillo recalls a woman from Colombia who recently quit her job at a laundromat after her boss physically abused her. She was unwilling to report him to the police. But with Castillo's encouragement, she filed a report with the New York Department of Labor. She later received two weeks of pay she had been shorted when she had to abruptly leave her position.

"I saw many violations for my people. Sometimes they don't get paid, or they get paid less than they should," explains Castillo, who is not from an indigenous community. "When they come to school, they get the skills they need to stand up for themselves and advance."

Castillo now runs 10 informal schools, under the umbrella of Volunteer Unit for Adult Education, in churches and hospitals in New York City; neighboring Westchester County, N.Y.; and New Jersey.

He operates with no budget, relying on borrowed classroom space, the help of 26 volunteers, and donations.

His classes offer one of the few venues in New York where Latin American immigrants can prep for their high school equivalency General Educational Development (GED) test free of charge.

"Many people like me didn't study in school in the past and didn't have the opportunity to," says Rufino Pavia, a landscaper of Mixteco descent. "Now we are being given that chance."

On a recent Sunday morning, Mr. Pavia sat around a table with nine other students in a windowless room of Our Lady of Good Counsel Parish in Staten Island. Four of them said they considered Spanish to be their second language.

As their volunteer teacher, a domestic worker from Mexico, called on students to come up to the chalkboard and write a sentence, Castillo paced the room.

"Go quickly, write something!" he told the students, who smiled shyly from their seats. "It doesn't matter what it is."

It can take students two years to master basic literacy, math, social studies, and science. From there, they typically require 72 hours of classwork for pre-GED study and 144 hours to prepare for the GED exam.

Some students think shorter term.

"I want to learn Spanish because I need to know it," says Librado Reyes, who is of Mixteco descent. "It is everything."

Castillo has had students who go on to earn college degrees in engineering and social work. But others grow impatient.

"They say, 'I've studied with you for six months, and I have nothing,' " Castillo says. "But the things I am teaching, you can't see. They are given skills, but they have to use the skills to gain success."

• To read more stories about people making a difference, go here.