South Africa says a final goodbye to Mandela

Loading...

| Qunu, South Africa

Nelson Mandela was buried Sunday in the African ground he loved after a funeral ceremony that included a 21-gun salute and fly-overs by military aircraft as well as a eulogy by a traditional leader wearing an animal skin.

Mandela's casket was lowered into the earth after military pallbearers carried it to the family gravesite in the rolling hills of Qunu, the rural village in eastern South Africa which was the childhood home of the anti-apartheid leader who became the country's first democratically-elected president.

Banyanda Nyengule, head of the Nelson Mandela Museum in Mthatha and Qunu, was one of the eyewitnesses to the private burial and said it hit him hard.

"I realized that the old man is no more, no more with us you know," Nyengule said. "The moment when the coffin went down into the ground I felt too ... emotional."

South African television showed Mandela's casket at the family gravesite, but the broadcast went to a different scene just before the coffin was lowered at the request of the Mandela family.

It was South Africa's final goodbye to the man who reconciled the country in its most volatile period.

Several hundred people attended the burial. Earlier, more than 4,000, some singing and dancing, gathered for a funeral service in a huge tent at the family compound of Mandela, who died Dec. 5 at the age of 95 after a long illness. They sang the national anthem in an emotional rendition in which some mourners placed fists over their chests.

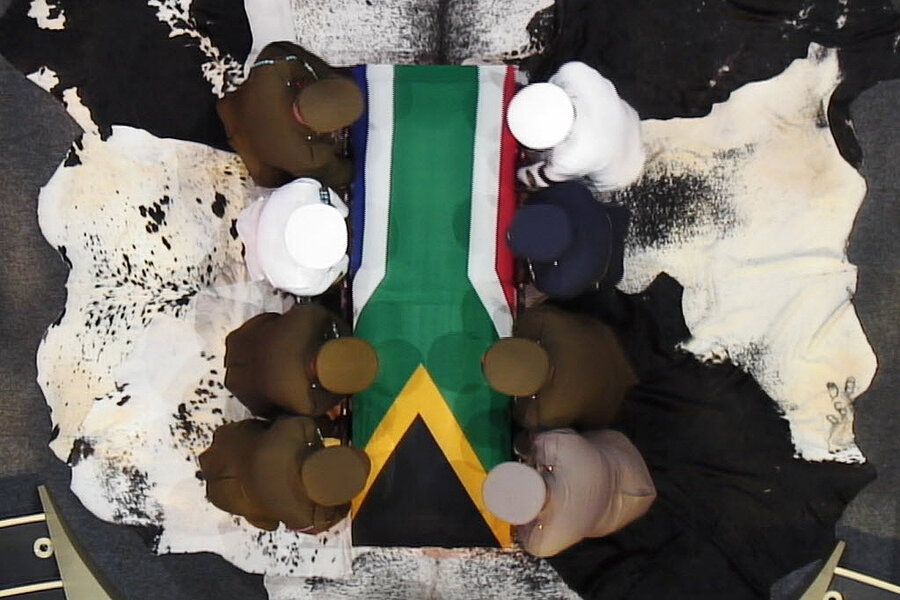

Mandela's portrait looked over the assembly in the white tent from behind a bank of 95 candles representing each year of his remarkable life. His casket, transported to the tent on a gun carriage and draped in the national flag, rested on a carpet of cow skins below a lectern where speakers delivered eulogies.

"A great tree has fallen, he is now going home to rest with his forefathers," said Chief Ngangomhlaba Matanzima, a representative of Mandela's family who wore an animal skin. "We thank them for lending us such an icon."

The tent ceremony was broadcast on big screens in the area, including at one spot on a hill overlooking Mandela's property. Several hundred people gathered there, some wearing the black, yellow and green colors of the African National Congress — the liberation movement-turned political party that Mandela had led — and occasionally breaking into song.

Nandi Mandela said her grandfather went barefoot to school in Qunu when he was boy and eventually became president and a figure of global import.

"It is to each of us to achieve anything you want in life," she said, recalling kind gestures by Mandela "that made all those around him also want to do good."

In the Xhosa language, she referred to her grandfather by his clan name: "Go well, Madiba. Go well to the land of our ancestors, you have run your race."

Ahmed Kathrada, an anti-apartheid activist who was jailed on Robben Island with Mandela, remembered his old friend's "abundant reserves" of love, patience and tolerance. He said it was painful when he saw Mandela for the last time, months ago in his hospital bed.

"He tightly held my hand, it was profoundly heartbreaking," Kathrada said, his voice breaking at times. "How I wish I never had to confront what I saw. I first met him 67 years ago and I recall the tall, healthy strong man, the boxer, the prisoner who easily wielded the pick and shovel when we couldn't do so."

Some mourners wiped away tears as Kathrada spoke, his voice trembling with emotion.

Mandela's widow, Grace Machel, and his second wife, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, were dressed in black Xhosa headwraps and dresses. Guests included veterans of the military wing of the African National Congress as well as United States Ambassador Patrick Gaspard and other foreign envoys.

Britain's Prince Charles, Monaco's Prince Albert II, U.S. television personality Oprah Winfrey, billionaire businessman Richard Branson and former Zimbabwean Prime Minister Morgan Tsvangirai were also there.

South African honor guards from the army, navy and air force marched in formation amid rolling green hills dotted with small dwellings and neatly demarcated plots of farmland. Clouds cast shadows over the landscape.

The burial ended 10 days of mourning ceremonies that included a massive stadium memorial in Johannesburg and three days during which Mandela's body lay in state in the capital, Pretoria.

Mandela spent 27 years in jail as a prisoner from apartheid, then emerged to lead a delicate transition to democracy when many South Africans feared the country would sink into all-out racial conflict. He became president in the first all-race elections in 1994.

While South Africa faces many problems, including crime, unemployment and economic inequality, Mandela is seen by many compatriots as the father of their nation and around the world as an example of the healing power of reconciliation.

In the final benediction, shortly before Mandela's casket was lowered into the eart, the chaplain general of the South African military, Brigadier General Monwabisi Jamangile said: "Yours was truly a long walk to freedom and now you have achieved the ultimate freedom in the bosom of your maker, God almighty. Amen."

Gregory Katz and Alan Clendenning in Johannesburg contributed to this report.