Costa Concordia: No 'Plan B,' in case problems arise when ship is righted

Loading...

| Rome

An international team of engineers and other experts has devised no "Plan B" if an attempt to right the hulking wreck of the grounded Costa Concordia goes wrong and the cruise liner splits apart or falls back on its side near an Italian island.

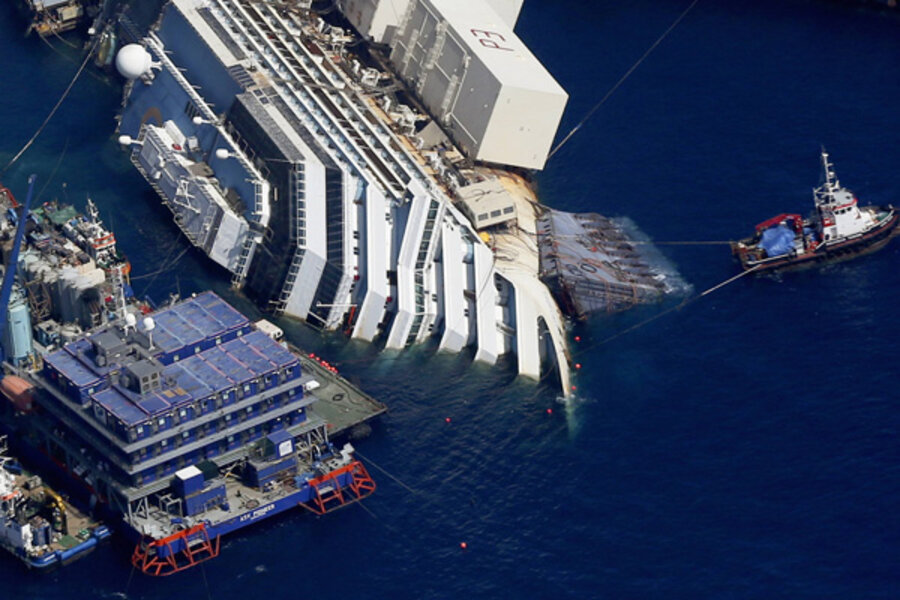

The team is attempting an unprecedented engineering bet to remove the luxury liner from just outside the harbor of Giglio island where it has been lying on its side after smashing into a jagged reef. Assuming seas are calm, the ship will be slowly pulled to the vertical in an hours-long operation so it can be towed to a mainland port and turned into scrap.

The possibility that the Mediterranean cruise liner might fall apart is a "remote event," insisted Franco Gabrielli, head of Italy's Civil Protection agency, at a briefing Thursday to lay out logistics. "If the ship doesn't turn" back upright, "there is no other way" to try it again.

Thirty-two people died when the Concordia crashed on the evening of Jan. 13, 2012, as the captain steered the vessel close to the island of Giglio's rocky coastline. The reef sliced a 70-meter (230-foot) long gash into a side of the hull, seawater rushed in and the Concordia began to lean over on one side, listing so quickly that many lifeboats couldn't be lowered to help save the 4,200 passengers and cruise aboard the pleasure cruise.

A 500-member salvage team from 24 nations will be conducting the operation to move the ship, known in nautical terms as parbuckling, before autumn storm season arrives, when winds and powerful waves risk battering it to the point it won't hold together.

Dozens of crank-like pulleys will start slowly rotating the ship upright at a rate of about 3 meters (yards) per hour. Steel chains weighing 17,000 tons have been looped under the vessel to help pull it upright. Tanks filled with water on the exposed side will also help rotate it upward.

Although parbuckling is a tested way to set upright capsized vessels, the operation has never been applied to a huge cruise liner.

Engineer Nick Sloane, a South African who is senior salvage master, said the Concordia will suffer an "extreme amount of force" of compression in the first part of the maneuver. But "we're pretty satisfied" the vessel will survive the stress, Sloane said. "We expect her to come up" to vertical, he said. "We're quite confident."

"She's resting in pristine waters on this hill" of two massive pieces of sloping granite seabed, Sloane said. He likened the ship's hull bottom to a "big belly .... about the size of a football field" perched on the two reefs.

Months ago, divers inserted cement-filled bags and grouting between the reefs to provide more stability. The aim of the parbuckling is to set the wreck upright on an underwater platform that has been installed.

"The objective is to get her to move very slowly and gently," Sloane said.

Engineers indicated they would be anxiously watching the early parts of the effort. Once the ship moves upward some 25 degrees, "at that point gravity takes over, and at that point, we start feeling relief," Sloane said.

Many of Giglio's 1,500 inhabitants work or go to school on the mainland, and authorities will let one last ferry sail from the island at dawn Monday. But no ferries or other boats will be allowed until the effort is completed. If seas are rough, or a storm looms, the ship's rotation will be postponed to a later day next week.

To cushion the more delicate bow on the Concordia, crews have cradled it in protective material, a measure likened to putting a protective neck brace around an accident victim before being moved.

Bodies of two of the 32 victims, an Italian passenger and a Filipino crew member, were never found. Once the ship is set upright and stabilized, it interior will be searched again in hopes of finding their remains, authorities said.