Nobel laureate for literature Mo Yan urges China dissident Liu Xiaobo's freedom

Loading...

| BEIJING

China's newly named Nobel laureate for literature expressed hope Friday that an imprisoned Chinese winner of the Nobel Peace Prize will be freed, putting a dent in the ruling Communist Party's attempts to burnish its credentials with the latest prize.

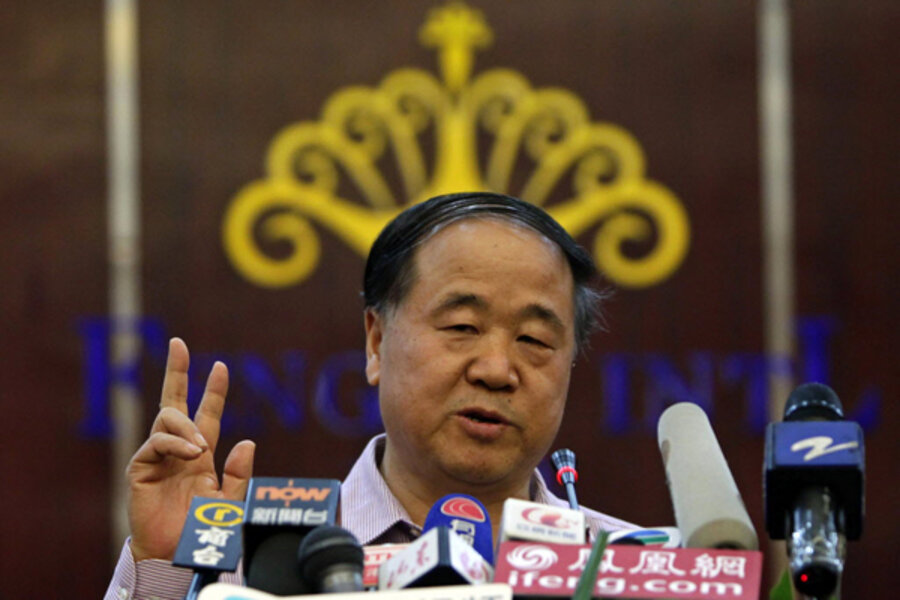

Mo Yan, the first Chinese writer to win the literature Nobel, made the comments about dissident Liu Xiaobo, who was awarded the Peace Prize while serving a prison sentence for opposing single-party rule, in response to a question at a news conference.

"I now hope that he can regain his freedom very soon," Mo Yan said. "If (Liu) can be freed in good health sooner, then he can study his politics and his social system."

He didn't elaborate, but Mo — who is a Communist Party member — appeared to be arguing that releasing Liu might allow the dissident to be convinced to embrace the party line.

His statement on Liu in his hometown of Gaomi in Shandong province came amid criticism by human rights activists that Mo compromises his artistic and intellectual independence by being a party member and vice president of the official writers association.

The call for Liu's release came just after the party's propaganda chief, Li Changchun, issued congratulations toMo, saying the award "reflects the prosperity and progress of Chinese literature, as well as the increasing influence of China."

News of Mo's historic win was plastered across newspaper front pages Friday.

The nationalist tabloid Global Times praised Mo's award as a sign of Western acceptance of mainstream Chinese culture. As one of China's most popular writers, Mo represents a rising China in both the economic and cultural spheres, the paper said in an editorial.

"The Chinese mainstream cannot be refused by the West for long," it said.

The response was a stark contrast to two years ago when the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Liu, who was sentenced to 11 years in prison in 2009 for co-authoring a bold call for ending single-party rule and enacting democratic reforms titled Charter 08.

The Chinese government rejected that honor, calling it a desecration of the Nobel tradition, and chilled relations with Norway, where the prize is awarded but whose government has no say in whom it goes to. China's rulers forbid opposition parties and maintain strict control over all media.

On Friday, Paris-based advocacy group Reporters Without Borders released a video showing the silhouette of a lone woman identified as Liu's wife, Liu Xia, smoking by a window at night in the apartment where she has been under virtual house arrest since October 2010.

The group did not say how it obtained the footage but said it was difficult and indicative of Liu Xia's imposed isolation and the near impossibility of approaching her.

"Smoking a cigarette at her window is one of the few freedoms left to her," said the group, which demanded the release of both Liu Xia and her husband.

Chinese officials have refused to discuss Liu Xia's condition, despite the lack of a legal justification for her confinement.

Prior to Mo's comments, famed artist and activist Ai Weiwei told The Associated Press that Mo was cooperating with a system that was "constantly poisoning" its people.

"They mock the ones who dare to raise their voice and opinion, and ignore the sacrifice some have made to gain that right. This is shameful. It is a shame for the Swedish Nobel Prize committee," Ai said.

At his impromptu news conference, Mo said he'd known Liu, but the two hadn't been in contact for some time.Mo, 57, and Liu, 56, attended the same school, Beijing Normal University's Luxun Literature Institute, 10 years apart.

"I didn't have any more exchanges with (Liu) after he left literature and embraced politics," Mo said. "I don't know really much about many of his activities."

On Friday, searches for "Liu Xiaobo" or "Nobel Peace Prize" were being censored on Chinese search engines and social media sites, but looking up "Mo Yan" or "Nobel literature prize" was allowed.

Mo's win also won sweeping coverage in democratic Taiwan, which China claims to be part of its own territory.

The island's culture minister, Lung Ying-tai, on Friday called Mo "a man of humor" who has used that wit to avoid possible persecution.

Lung, a noted essayist, said the prize may help Chinese "open up their minds and hearts" and engage the world through literature.