Good Reads: Syria's conflict, hero journalists, and the power of parents

Loading...

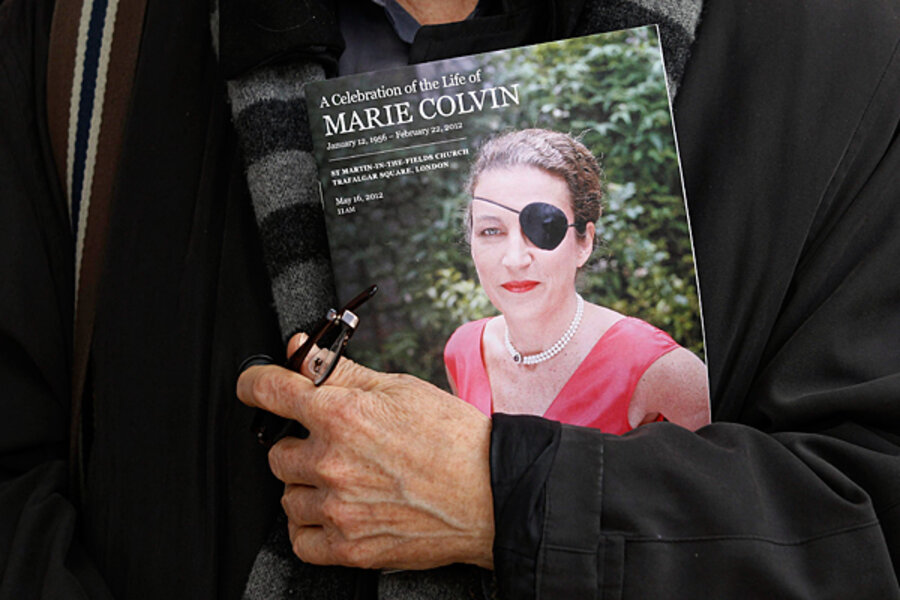

Being Marie Colvin

The news reports that come out of Syria on a daily basis often leave more questions than answers. How do ordinary people survive in such a war? How can a country’s leader order his military to fire artillery shells into packed urban areas, knowing that such actions will cause civilian casualties by the thousands?

The late foreign correspondent Marie Colvin was obsessed by these questions. Like many war correspondents, she ran toward the sound of gunfire, while everyone else was running away. In February of this year, she had herself smuggled by Syrian opposition members into the besieged city of Homs to document what she considered a terrible war crime, made more terrible by the fact that no one was there to see it, or to stop it. It was an assignment that would cost her her life.

Why did she do it? Marie Brenner in Vanity Fair explores the past of this teacher’s daughter from Long Island, and her dangerous passion for being an eyewitness to history:

For Colvin, the facts were clear: a murderous dictator was bombarding a city that had no food, power, or medical supplies. [NATO] and the United Nations stood by doing nothing. In a nearby village, hours before they left, Conroy had watched her trying to get a signal and file her story for the next day’s paper on her vintage satellite phone. “Why is the world not here?” she asked her assistant in London. That question, posed by Colvin so many times before — in East Timor, Libya, Kosovo, Chechnya, Iran, Iraq, Sri Lanka — was the continuing theme of her life. “The next war I cover,” she had written in 2001, “I’ll be more awed than ever by the quiet bravery of civilians who endure far more than I ever will.”

Lawrence of Syria

The black-and-white morality of the Syrian conflict – symbolized by Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad’s overwhelming use of force, and by the cruelty of his intelligence service in torturing opponents and dissidents – doesn’t make it any easier to find a solution to the crisis.

Former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan has been struggling with this question for months, with few results. Support for Assad from Russia and China doesn't make it any easier.

But should the world intervene militarily in Syria? It’s a question that T.E. Lawrence, better known as “Lawrence of Arabia,” had an answer for: No.

For Captain Lawrence, then helping the Hashemite tribes of the Arabian peninsula overturn Ottoman rule during World War I, Syria was a nest of petty political figures, all interested in the gain of their own extended families or communities. And in any case, Franz-Stefan Gady writes in the National Interest magazine, military success would be meaningless if it didn’t lead to a lasting political settlement afterward.

The major lesson Lawrence drew from the history of foreign interventions in Syria, starting from the Ottomans to the British and French, is that they have been marked by disappointment. The defeats have come not so much in military struggles — both the British and French prevailed in that sphere — but in the failure of political settlements and the transition to peace once the fighting ceased.

A grateful son’s tribute

One of the most moving stories I read this week was a tribute, written by David Rothkopf in Foreign Policy, about his father who had just passed on. Mr. Rothkopf’s father was a Holocaust survivor, who fled the Nazis in Austria for the US, where he joined the US Army and returned to Europe commanding a battery of howitzers.

Rather than obsess on his own struggles, the senior Rothkopf focused on the future, and specifically the education of the next generation. As David Rothkopf writes, “We talk too easily of 'the Greatest Generation,' as if their primary contributions were in fighting a great war or building America into a great superpower.”

What the best of them have revealed was that what makes great nations great is always measured not by how much we spend on or our militaries or the edifices of our states but by what and how we invest in our classrooms and our laboratories and in the minds and futures of our children.

Sexual harassment and us

Somewhere on YouTube, there is a video of a young woman in the northeastern Indian city of Guwahati that has gone viral. The video shows her being sexually assaulted by a crowd of men.

The sexual harassment of women in India is so common, it has a nickname: Eve-teasing. And, as the name implies, there is a prevalent view in Indian society that the real person at fault in such an incident is the woman, Eve, for tempting the men.

The harassment takes place in public, and most people simply look away. The victims largely remain silent, afraid to even confide in their own families. Natasha Badhwar was one of those victims, and she writes of her own experience in The Wall Street Journal affiliated blogsite Live Mint about how this current video scandal has awakened in her a determination to channel her own experiences to make a difference in her society.

“What is the difference between the world that I grew up in and the world our children are growing up in?” she asks. “It’s a one word answer. I am the difference.”

As the father of two daughters, I found this powerful.