For Syrian refugees in Lebanon, a drive to build community amid pressing challenges

Loading...

| Beirut, Lebanon

I remember Syrian children living by a garbage dump near a cement factory where their parents did menial labor when I visited Lebanon three years ago. I remember those living in an unfinished shopping mall with open storefronts, several families camped in a space supposed to be a shop, except that the developer had run out of money and never finished the building. Now he could collect rent from the refugees.

Syrian refugees were pouring into Lebanon in 2014, fleeing the civil war. The United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) and nongovernmental organizations were scrambling to register and provide services for these families, most of whom hoped to return to Syria when the war was over. Because Lebanon has a history dating back to the Palestinian diaspora of not providing camps for refugees, the displaced were finding shelter wherever they could. The effort to get children into schools was beginning. One aid worker described the situation as trying to give cups of water to people from a blasting firehose.

I recently returned to Lebanon to visit the Syrian refugees. I was in Beirut when President Trump’s edict on immigration and his ban on all Syrian refugees to the United States was announced. The ban included Syrian families in Lebanon who had been going through the long vetting process to resettle in the US. Lebanon has the largest percentage of refugees given its population – more than 1 million registered in a country of 4.5 million citizens.

The situation in Lebanon remains deeply challenging, with pressing needs. But it has stabilized. The flow of people across the border is now a trickle, not a flood, and the systems to assist are more firmly in place. When the refugee population hit the 1 million mark, Lebanon changed its open border policy. But the Syrian refugees remain more than 20 percent of Lebanon’s population, the equivalent of 64 million in the US. Last year the United States accepted 10,000 Syrian refugees out of an estimated 4.8 million worldwide.

Three years ago, Lebanon had only 150 schools that had split shifts, teaching the Syrian children in the afternoon. Today half of the Syrian children are in government schools – more than 200,000 children, according to UNHCR officials. UNHCR pays the Lebanese Ministry of Education $600 per child to assist in the cost. Some children may be enrolled in private schools, according to officials, though the remaining are still not in school, including those who work to bring in income for their families, and, in the case of girls, those who are married off as young as 14 or 15.

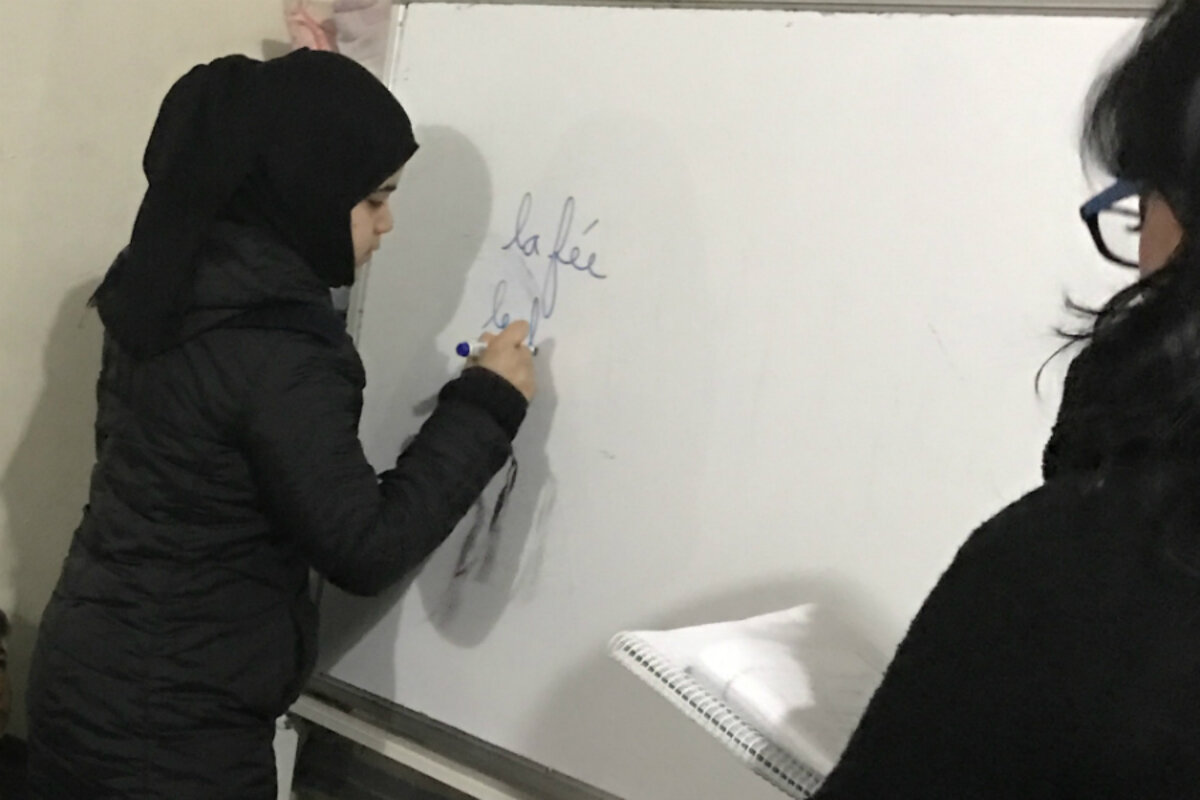

Writing plays and tutoring in French

A difficulty for Syrian school children is language; Lebanese schools teach in French or English in addition to Arabic. One 12-year-old girl dressed in black headscarf practiced French with a local volunteer in a homework support group. The girl has been living in Lebanon for 3-1/2 years. She was in fifth grade when she left Syria, but she’s lost years of schooling, and because she doesn’t know French, she is now placed in third grade. She is friends with some of the Syrian children in her school, but with few Lebanese children. “They don’t like to talk about the same things,” she said. “What do you like to talk about?” I asked. “I want to talk about the war.”

Hasan, 13 years old, remembers going to school in Aleppo, and has been in Lebanon three years. He’s glad to be in school again, but he too has lost several years of education and is in an early elementary class.

For elementary school children, the transition is not as difficult since they can learn French or English, but older Syrian students are struggling. Homework support groups have grown up and are sustained by UNHCR and Save the Children. In Batroun, a town in the North, a Lebanese teacher volunteers twice a week to tutor French. Other outreach volunteers assist in other subjects. One young man, Joseph, helps the children by writing plays and doing small theater productions with them. A Syrian, he receives his work expenses and training. But, he said, “I volunteered to help my people. At the beginning I wanted to volunteer in any sector, but I believe education is very important. I started a small theatrical team, selected the children, wrote small plays with a message, and we perform in a small garden Saturday or Sunday for the community.”

Building communities has been essential for the children and their families, especially since return to Syria remains problematic. These communities grow up in the buildings and spaces where the families live. Approximately 60 percent of the refugees rent apartments, often crowding several families into one or two rooms, carpets and pillows on the floor, a single television in the corner, a light bulb on the ceiling. UNHCR has helped in reconstruction of buildings with an agreement from the landlords that they will rent at reduced rates to the Syrian refugees for a period. Other refugees have built temporary shelters on the roadside. Simple wood frames with tarps and plastic sheeting dot the landscape in the north, perched on farmers’ land where refugee men and women work in fields of orange groves, olives, cucumbers, and potatoes.

Guests, with work restrictions

The Lebanese government has said it is treating the Syrians as “guests” and does not deport them, but the government restricts where the Syrians can work. To get a residency permit, they have to agree not to work except in agriculture, construction, or environment (cleaning) – all low-wage areas. The government also requires that refugees re-register every six months, paying $200 per person over 15 years of age. The cost is prohibitive for many families, so the men in particular live in fear that they will be arrested for not having proper registration, and this limits their mobility in finding employment, according to aid workers.

While refugee services from the UN, nongovernmental organizations, and the Lebanese government have increased in recent years, so have the poverty rates, as families have spent the money they brought with them. According to UNHCR statistics, 70.5 percent of the refugee population live in “extreme poverty,” meaning they live on less than $3.80 per day. UNHCR provides cash assistance, but to only 22 percent of these families. With the cash cards they can buy food, supplies, and pay rent. As winter arrived, additional small payments were provided to help buy blankets, warm clothes, and fuel.

Many of the refugees say their hope is in giving their children a better future, but in Lebanon that future has a ceiling. “At least we have a real school now and one close. It is much easier for our children,” says one mother. But with livelihood possibilities tightly controlled and the possibility of affordable residency curtailed, many parents don’t see an expanding future in Lebanon. UNHCR tries to assist those who want to resettle elsewhere, but even before the recent US ban on Syrian resettlement, the possible openings were diminishing.

“UNHCR’s top recommendation in Lebanon is a waiver of the residency fee so that the refugees are all legally registered and can work. This will help provide employment for them and a work force in needed areas of Lebanon, and income that can then be spent in the local economy,” says Karolina Lindholm Billing, UNHCR deputy representative.

“When you used to look out over Beirut at night, you would see black on top of the buildings,” she notes. “Now you see the lights of refugee settlements there – tents and cooking fires. The refugees have found whatever space is available and gotten permission from the landlords and pay rent.”

Joanne Leedom-Ackerman is a novelist and journalist who has traveled in the Middle East and visited the refugee settlements in all the countries bordering Syria and has recently returned from Lebanon. Ms. Leedom-Ackerman is a former reporter for the Monitor.