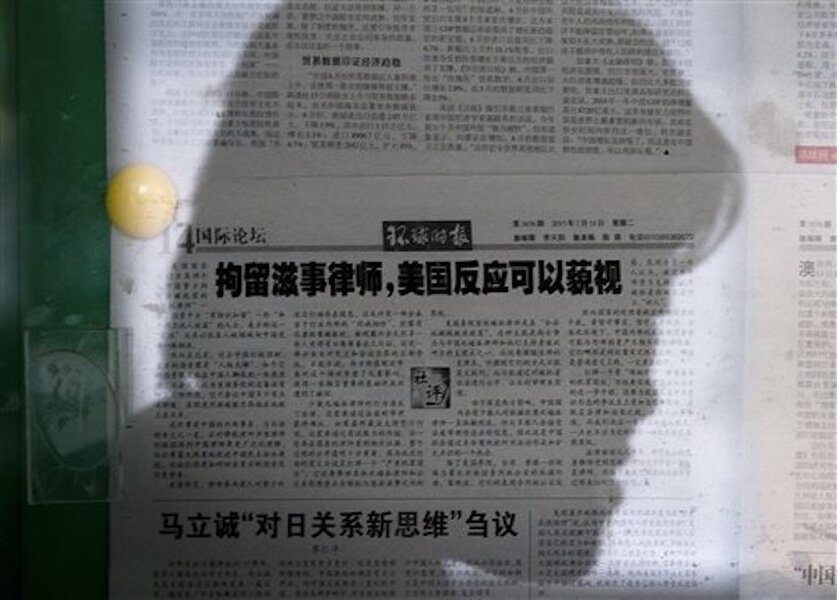

China accuses human rights lawyers, activists of inciting 'mob rule'

Loading...

At least 24 human rights lawyers and activists have been detained or went missing in China since last Thursday, Amnesty International reports. As the government continues its nationwide crackdown on civil disobedience, authorities have targeted over 100 lawyers and human rights activists for questioning and searched at least three law firms.

On Tuesday, China's official Xinhua News Agency wrote that China's Ministry of Public Security suspects persons associated with Beijing's Fengrui law firm have been working to “disrupt public order, seek illegal profits, illegally hire protesters, and...unfairly influence the courts.”

The security ministry accused the group of organizing more than 40 “controversial incidents” and warned them not to “undermine the law by rabble-rousing in the streets.”

The government appeared to step up its measures against human rights lawyers last week, after Wang Yu, a leading member of the Fengrui law firm, went missing last Wednesday. Ms. Wang was known for defending figures like Uighur scholar Ilhem Tohti and free speech advocates in court over recent incidents.

Many of those detained since then were part of a group of over 100 lawyers and rights activists who signed a public statement on Thursday condemning Wang's disappearance, says Amnesty International. The authorities who questioned the lawyers and activists focused on the statement and wanted to know whether they were involved.

The Ministry of Public Security claimed it’s been forced to crack down on dissent after human rights activists and lawyers joined efforts to criticize social injustice and government impunity in recent advocacy campaigns.

A notable case known as the “Qing’an Incident,” sparked a nationwide controversy last May after a police officer fatally shot a petitioner at a train station in Heilongjiang province. Fengrui’s Wang Yu was one of the most outspoken critics of the government’s handling of the case, according to a watchdog group, Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD).

“The deteriorating human rights conditions in China under President Xi Jinping have now reached a point of crisis,” wrote CHRD in a statement Monday condemning the government’s latest string of arrests.

Last month, the government formally charged Pu Zhiqiang, an outspoken and prominent human right lawyer, with inciting racial hatred and “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” on social media. Authorities held Zhiqiang in custody for a year and he now faces a potential 10-year jail sentence.

"The Communist Party calculates that only by becoming more severe can it control the rapid growth of civil society,” Teng Biao, a human rights lawyer and fellow at Harvard Law School, told The Christian Science Monitor.