Friendly with the Dalai Lama? Good luck talking with Beijing

Loading...

| Beijing

Prince Charles, heir to the British throne, has never had very good relations with the Chinese government. But now his personal envoy to Beijing is offering to help another British leader who seems to be even more firmly in the Chinese doghouse – Prime Minister David Cameron.

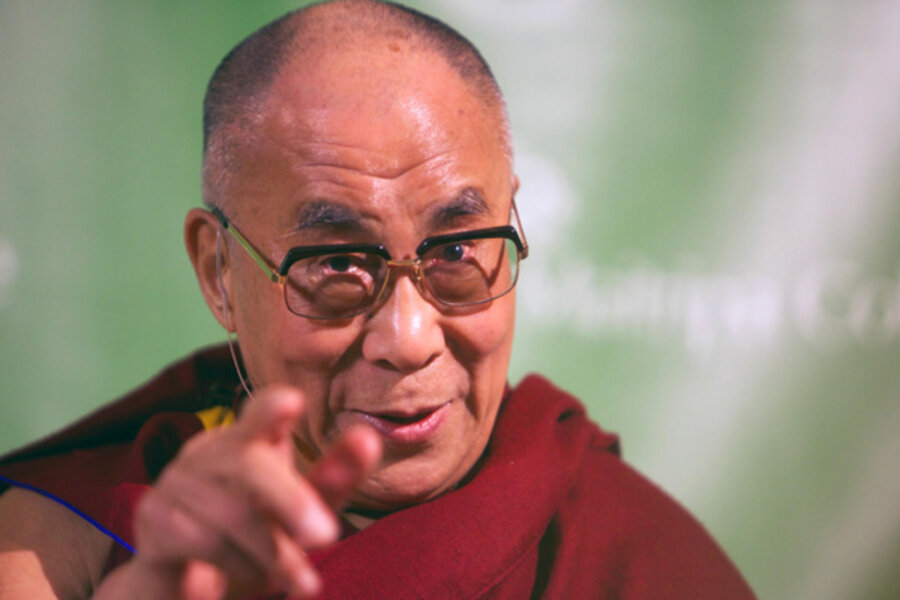

Mr. Cameron, who would dearly like to head a trade and investment mission to China, incurred Beijing’s wrath last May by meeting the Dalai Lama. The fact that it was a private meeting, on sacred ground in St. Paul’s cathedral, makes no difference. He will be persona non grata until he apologizes.

That status can be costly: A 2010 study by academics at the University of Gottingen in Germany found that countries whose top leadership received the Dalai Lama lost an average of 8.1 percent of their exports to China over the following two years, though the effect wore off after that punishment period.

Enter Sir David Tang, Hong Kong fashion tycoon and flamboyant London socialite, who also heads Prince Charles’s charitable foundation in Beijing. He told the Daily Telegraph’s gossip columnist over the weekend that he is ready to help defrost London’s diplomatic relations with Beijing.

“Look at the Prince of Wales,” he told the paper. “He’s now very engaged with lots of Chinese people.”

’Twas not ever thus. The Prince’s stock here hit rock bottom in 2005 when somebody leaked the private diary he had kept in 1997, when he represented the Queen at the handover of Hong Kong to Chinese sovereignty in 1997. He famously described the assembly of top Chinese leaders at the ceremony as “appalling old waxworks.”

In 2009, however, Prince Charles opened a Chinese branch of his international foundation, funding projects that build sustainable communities. That has helped, but he has still never visited mainland China.

Charles himself is close to the Dalai Lama, which makes him a suspicious character in Beijing’s eyes. The Chinese authorities go to extraordinary lengths to persuade foreign leaders not to meet the Tibetan leader, whom they accuse of being an anti-Chinese “splittist,” and when those leaders fail they grow very angry.

Former French President Nicolas Sarkozy was subjected to such anger when he met the Dalai Lama.

France emerged from such a period of diplomatic and trade punishment in 2009, only after it signed a joint statement with China clarifying that Paris “fully appreciates the importance and sensitivity of the Tibet issue and reaffirms … that Tibet is an integral part of Chinese territory.”

Since the Dalai Lama himself has also said, repeatedly, that Tibet is part of Chinese territory, and that he does not seek independence, French diplomats could argue that they were not conceding anything. But the symbolism of the statement was clear.

London appears to have escaped the export boycott: A British government spokesman pointed out that UK exports to China had climbed by 13.4 percent last year.

He also defended Cameron’s right to choose who he meets in private regardless of China’s feelings on the matter. “It is entirely reasonable for the prime minister to decide who he meets,” the spokesman said.

But no sooner had the queen finished her speech opening Parliament last Wednesday, than Cameron was offering olive branches to Beijing. A senior member of the ruling Conservative Party lobbed the prime minister a clearly pre-arranged question about Sino-British relations; Cameron lost no time in reassuring Parliament, and Beijing, of course, that “we recognize Tibet as part of China. We do not support Tibetan independence and we respect China’s sovereignty.

“We do want to have a strong and positive relationship with China,” he stressed.

It remains to be seen whether this will be enough to placate Beijing.