How native Americans hid in the Vatican for more than 500 years

Loading...

| Rome

More than 500 years after Christopher Columbus set foot on the shores of the New World, what may be the first-ever depiction of the native Americans he encountered has been discovered hidden in a Vatican painting.

The discovery was made by restoration experts who were cleaning a large fresco painted by the Renaissance master Pinturicchio. Once they had removed layers of dirt, they noticed a group of tiny figures, almost in the middle of the painting.

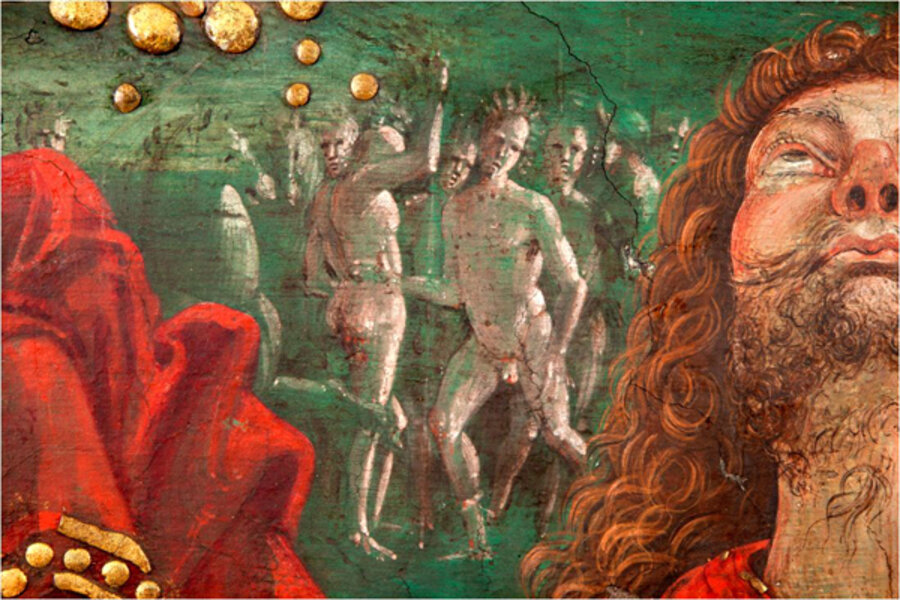

The figures are men who seem to be dancing and are naked except for exotic-looking feather headdresses. One appears to have a Mohican-style haircut.

Pinturicchio created the work, which shows Jesus' Resurrection, in 1494, just a year after Columbus returned from his first journey of discovery across the Atlantic.

The head of the Vatican Museums, Antonio Paolucci, believes that the mysterious figures represent some of the native Americans whom the Genoese explorer met as he sailed around the Caribbean.

Professor Paolucci announced the discovery of the long-lost image in the Vatican’s daily newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano, in an article titled “This is the first image of native Americans as described by Columbus.” He hypothesized that the “nude men, who are decorated with feathers and seem to be dancing,” were inspired by the descriptions of tribesmen that Columbus brought back from his travels.

The Pinturicchio painting, titled simply "Resurrection," has adorned the walls of the Borgia Apartments in the Vatican for centuries.

The apartments were named after the notorious Rodrigo Borgia, who became Pope Alexander VI. He commissioned Pinturicchio and his assistants to paint several frescoes for the apartments, which are part of the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace.

The tiny dancing figures remained unnoticed for so long because the Borgia Apartments were abandoned after the death of Pope Alexander in 1503. Subsequent popes did not want to be associated with the scandal-ridden family. They were only reopened in 1889 by Pope Leo XIII, and are now used to display a collection of religious art.

Columbus’s voyages across the Atlantic were commissioned by Spain, but Paolucci said the Vatican knew of his discoveries, particularly given that Pope Alexander was Spanish.

“The Borgia Pope was interested in the New World, as were the great chancelleries of Europe. It is hard to believe that the papal court, especially under a Spanish Pope, would have remained in the dark about what Columbus encountered,” Paolucci said in the article.

Pope Alexander soon found himself playing a pivotal role in the New World discoveries – he had to arbitrate between the competing claims of Spain and Portugal.

The pope had himself painted into the lavish fresco – dressed in sumptuous golden robes, he is kneeling down on the left side, his hands clasped in prayer.

He is clearly contemplating Jesus' resurrection, but he also appears to be directing his gaze at the tribesmen – ruminating, perhaps, on the enormous implications of Columbus’s historic discovery.