How a Quaker missionary from Philly became India's Johnny Appleseed

Loading...

| Himachal Pradesh, India

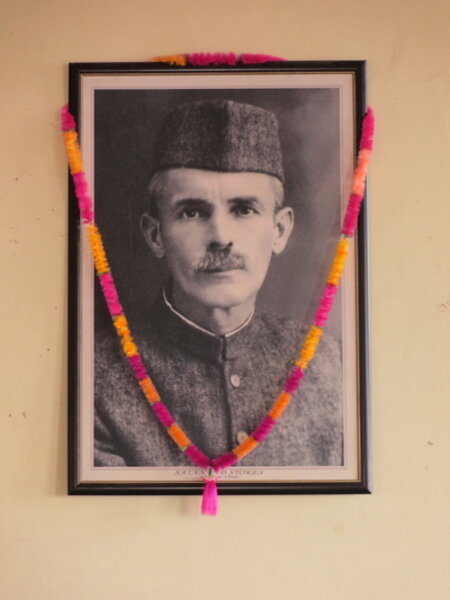

A community hall in rural India is not the place you would expect to find a garlanded portrait or statue of a Quaker missionary from Philadelphia. But both those things can be found at the farmers’ hall in Thanedar, the “apple bowl” of the Himalayan state of Himachal Pradesh in India.

Every farmer here can – and will – tell you about Samuel Evans Stokes, or Satyanand Stokes as he came to be known. He was an American missionary who settled in this area in the early 20th century, participated in India’s struggle for independence as a co-traveller of Mahatma Gandhi, and became the Johnny Appleseed of the northwestern Himalayas.

Stokes seeded a horticultural revolution when he planted five saplings of Red Delicious – bought from the Starks Brothers nursery in Louisiana – on his farm here in 1916, and helped convert locals to apple farming.

Stokes’s extraordinary journey began in turn-of-the-19th -century Philadelphia where, at a church meeting, he heard an American doctor talk about working with lepers in India. Inspired, this son of a wealthy Quaker family (the founders of the elevator manufacturers, Stokes and Parish Machine Company) gave up his post-graduate studies at Cornell University and joined the doctor on a steamship to Bombay in 1904.

For a time, according to family accounts, Stokes worked at the doctor’s home for lepers in the plains. He fell ill and was sent to recuperate in the hills near Shimla, then the summer capital of the British Raj, at a cantonment village called Kotgarh.

Smitten by Kotgarh – which Rudyard Kipling called “mistress of the hills” – Stokes stayed on. He experimented with renunciation, living in a cave like an Indian sadhu, and founded the Brotherhood of Imitation of Jesus, traveling from village to village preaching. A few years later, he married an Indian woman, bought a former tea estate in Thanedar, and focused on farming. In 1914, he took local soil samples to America, returning with Red Delicious stocks.

Stokes spent years trying to persuade his neighbors to grow apples, giving away plants freely, says Vidya Stokes, who married Samuel Stokes’s son, Lal Chand, and is the current horticulture minister of Himachal Pradesh.

Initially, few farmers listened, she said. They knew only the cooking apples the British had brought – Granny Smith and Pippin varieties that were too sour for Indian tastes.

Stokes taught the boys in the school he established how to graft the plants, says Vidya Stokes. “Their parents were skeptical, so the boys planted the saplings on the borders of their family farms,” she says.

When the first crops of Red Delicious came, however, “everyone came to see,” she says. “The apples were sweet. People realized they could make money from this.”

And they did – Himachal’s apple orchards are valued today at around $550 million and provide a livelihood to more than 100,000 farmers.

Farming wasn’t the only way in which Samuel Stokes sought to help society, however. A believer in racial equality and social justice, he campaigned successfully to end a colonial system of forced labor in the hills and joined the Indian freedom struggle: signing petitions, engaging in debates on strategy with Gandhi and other nationalists, and adopting Indian clothes.

In 1921, he was the only non-Indian to be invited by Gandhi to sign a nationalist manifesto calling on Indians to quit government service – he signed – and was imprisoned for six months on charges of sedition.

In his later years, Samuel Stokes became more contemplative. In 1932, he and his family converted to Hindusim and changed his name to Satyanand. The temple he built – without idols – as well as Stokes’s home can still be seen today on his 200-acre estate in Thanedar. Most of Stokes descendants now live in America.

Stokes’s portrait also hangs in the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library in New Delhi, alongside pictures of Mahatma Gandhi and other leaders of the Indian independence movement.

But it’s the farmers of Himachal Pradesh who remember him – as the man who transformed the region and their lives – with apples from America.