Was that the president in my Beijing taxi?

Loading...

| Beijing

When was the last time the Chinese president hailed a Beijing taxi?

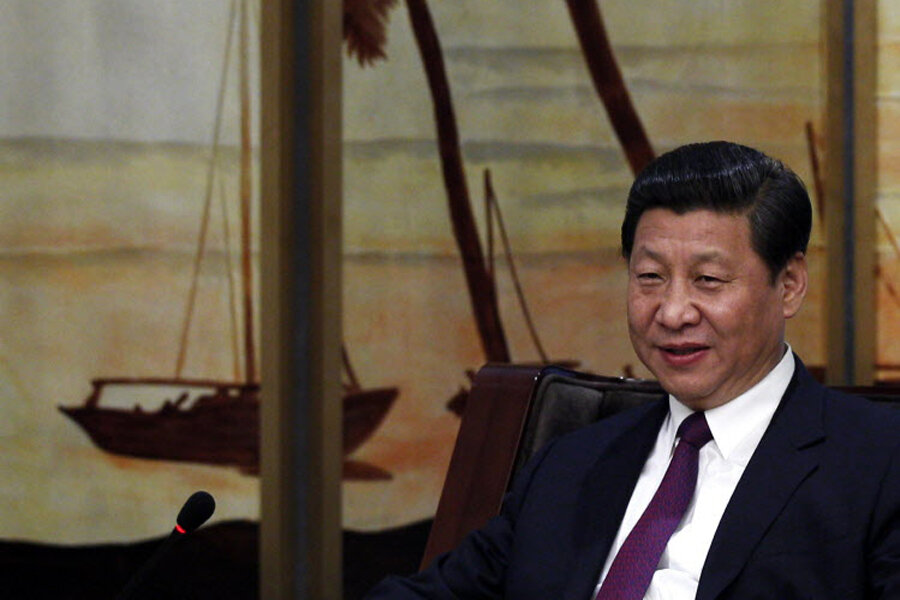

Just a few weeks ago, if taxi driver Guo Lixin is to be believed. Mr. Guo told a Hong Kong newspaper on Thursday that President Xi Jinping took an incognito ride in his cab last month, and chatted about – what else? – air pollution.

The news sparked enormous interest on the Chinese Internet, with most of those posting comments on Twitter-like social media platforms apparently believing the tale, but many skeptical about the value of the president’s alleged outing.

Stories about Chinese emperors passing disguised amongst their subjects, so as to learn first hand about their lives, are a staple of Chinese TV soap operas. The official media have recently made a point of presenting Mr. Xi as a “man of the people.”

According to Ta Kung Pao, the Hong Kong daily to whom Mr. Guo gave his account, two men got into his taxi on the evening of March 1. One of them, he said, looked uncommonly like Xi, head of China’s ruling Communist Party and on the verge of being elected the country’s president.

When he commented on the fact, his mystery passenger replied “you are the first taxi driver to recognize me,” Guo said, before writing a note wishing the driver “safe and smooth journeys.”

There are those who saw the story as a PR exercise, pointing out that Ta Kung Pao is a strongly pro-Beijing paper. Official Chinese websites ran the story, too, giving it a degree of credibility, or at least of government approval.

Other observers were dubious about the real identity of Guo’s passenger because the handwriting of his note had nothing in common with handwriting that the verified President Xi has left in visitors’ books around the country.

The story sat well, however, with the Communist Party’s propaganda efforts to build the president’s image as a forthright, honest fellow with the common touch. Xi has attracted attention by ordering the police not to block the traffic near places he is visiting just to let his motorcade past. Last week he mingled with fisherfolk on the southern island of Hainan, discussing their catch in the same way that a Western politician might on a flesh-pressing jaunt.

Not everyone is impressed, however. “The most effective plainclothes visit is to look at Weibo every day,” commented Feng Xincheng, a well known newspaper editor, referring to Sina Weibo, a censored but nonetheless lively Twitter-like service where public criticism of the authorities is common.

It did not seem from taxi driver Guo’s account that Xi (if it was indeed he) learned much that he did not already know. As soon as he recognized his passenger Guo broke out in a cold sweat, he said, and told the distinguished man in the front passenger seat that he thought the Communist Party and government policies were correct, if not always well implemented.

“Xi,” meanwhile, fed his ordinary citizen interlocutor the same pap as government officials feed the public about how long it will take and how hard it will be to clean up Beijing’s pollution.

Neither the alleged president nor his driver ended up much the wiser, it seems. And then on Thursday evening, the official Xinhua news agency stamped on all the speculation with a terse one line announcement.

Ta Kung Pao’s report, said Xinhua, “has proven to be a fake story.”