Why the planned Koran burning causes outrage and alarm

Loading...

| Boston

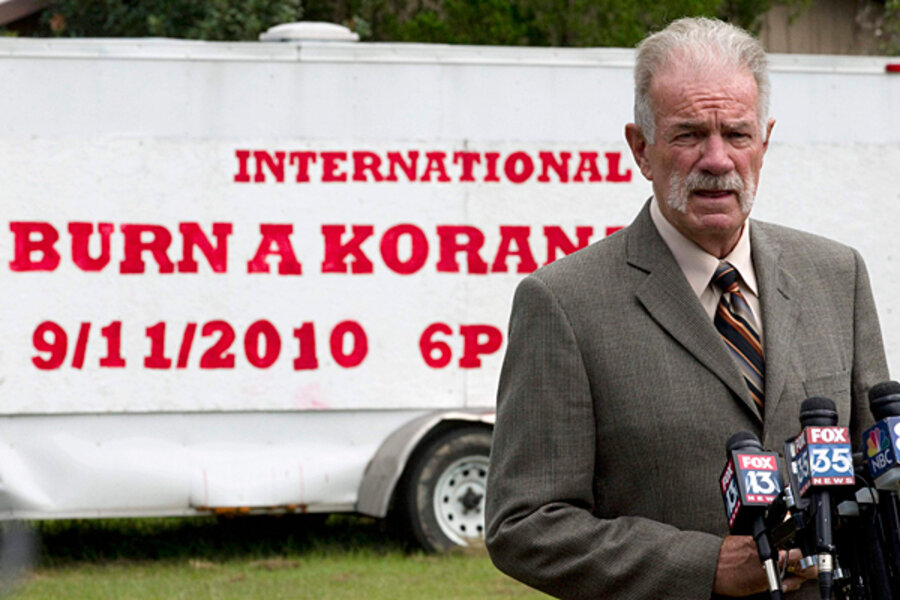

The Rev. Terry Jones, pastor of a small evangelical Christian church in Gainesville, Fla., has a legal right to burn the Koran. But understanding why this act, planned for Sept. 11, is so inflammatory, means understanding the special reverence with which devout Muslims view the Koran.

Muslims see it as the uninterrupted, unchangeable, and eternal word of God. Burning the Koran is akin to directly burning the word of God.

What’s more, Reverend Jones’s planned burning of the Muslim holy book is set for the day after the end of Ramadan, the month of fasting meant to commemorate the time in 610 when Muslims believe the angel Gabriel – the same Gabriel that appears to Daniel in the Old Testament – first appeared to the prophet Muhammad and began "revealing" the Koran to him.

Historians and linguistic scholars view the Koran as the work of Muhammad and his immediate successors, perhaps inspired by earlier Jewish texts.

Muslims, however, believe that the Koran was delivered to the prophet directly from God, from a book that had existed for all time but had been withheld from man until that point. From their religious view, the book was set down in writing without embellishment or error and has been unchanged from the time of the last revelation to Muhammad in 632.

That's one reason many Muslims argue that true understanding of the Koran can only come from reading it in Arabic (some say that a translated Koran is no Koran at all). It has also led to a host of traditions that honor the physical book, such as making sure the book is stored on the highest shelf in the house.

If the notion of burning Korans wasn’t enough to upset Muslims around the world, Jones added more fuel to the fire by saying: "Islam is of the Devil."

Anti-Muslim protests such as Jones’s Koran burning aren’t new. In the recent past, they have set off violent protests and had deadly results. There was the controversy over a series of cartoons of the Muhammad in Denmark's Jyllands-Posten newspaper in 2005. Those depictions offended many Muslims in Denmark and sparked global outrage with boycotts of Danish goods and riots in some Middle Eastern cities.

The pictures were published in September 2005, but global Muslim outrage only emerged early the next year, after a group of Danish imams toured the Middle East with a dossier of material that included offensive cartoons that were not part of the original Jyllands-Posten set. Newspapers across Europe republished the cartoons as a protest in favor of free speech.

That controversy was a boon to Muslim, Christian, and Jewish extremists who seek to portray the three religions as being fundamentally hostile to each other.

Al Qaeda acolytes seized on the cartoons as evidence of a global Christian plot to attack their faith; to some in the West, the violent reaction of a few Muslims was evidence that Islam is antithetical to modern, pluralistic values.

As heated as the anger over the cartoons and attempts to censor them were, the question of whether depictions of Muhammad are "un-Islamic" is not definitively settled within Islam.

The Koran does not address the question, though there are some stories of the prophet's life (hadith) that say he opposed the practice. Historically, Islamic art has run the gamut from fine Persian miniatures showing a full depiction of Muhammad to others that obscure his face to still others that place him in the middle of a scene as a flame or some other symbolic representation.

Burning of the Koran, from an Islamic religious perspective, is a far more provocative act. By his own admission, provocation is what Jones seeks.

There is one case of "koran" burning in history that Muslims praise. The story has it that Uthman, Muhammad's second successor as leader of the faithful, grew alarmed at the proliferation of stylistic and other changes in various texts in the decades after Muhammad's death. He had those "korans" collected and burned, leaving behind only what he and his aides viewed as the true Koran.