New climate change signal: oceans turning acidic

Loading...

COPENHAGEN, DENMARK -- Forget "climategate" and arguments over whether the Earth is really warming. If you need a simple, non-controversial scientific reason to support curtailing greenhouse gas emissions, stop looking skyward and look at the pH of the oceans.

At least that's the argument Jeffrey Short made Tuesday at the global climate change summit in Copenhagen. Dr. Short, the Pacific science director for Oceana, an environmental group working to protect the world's oceans, says that regardless of the impact on climate, the billions of tons of carbon-dioxide (CO2) that human activity pumps out every year is making oceans more acidic.

That's threatening fisheries that millions rely on for food and livelihoods. Already some shellfish, from commercially important crabs, clams, and mussels to tiny creatures called pteropods (dubbed the "potato chips of the ocean" for the important rung they occupy near the bottom of the marine food chain), are showing the effects of ocean acidification. Coral reefs, important nurseries for commercial fish species, are also being threatened.

The damage to the oceans should be enough on its own to push policy makers to sign a global agreement to reduce CO2 emissions, "even if carbon dioxide didn't do anything to warm the atmosphere," says Short, who spent more than 30 years as a marine scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) before entering the policy arena.

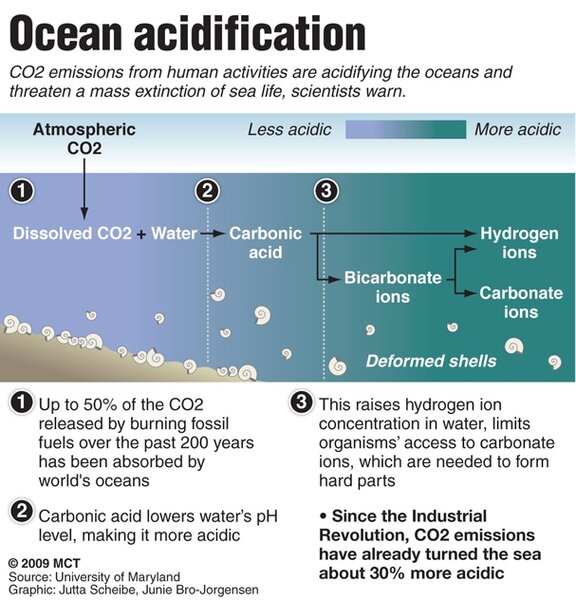

Ocean acidification refers to the effect CO2 has on seawater as the oceans take up the gas. The world's oceans absorb roughly 25 percent of the CO2 humans release into the atmosphere each year. That CO2 reacts with seawater to form small but increasing amounts of carbonic acid.

Shellfish as canaries in the coal mine

The change is virtually imperceptible to humans, but it's a different story for some marine animals that build shells. Shell building creatures rely on an excess of dissolved calcium carbonate in the oceans, built up from millenniums of rock erosion on land. More and more of this raw material for shells is being diverted to, in effect, neutralize the acid, leaving less dissolved carbonates for shell-builders to use.

Ocean acidification could harm coral reefs by taking up mineral aragonite in seawater that the small animals use to build the elaborate structures that are home to fish and protect coasts from storm surges.

To be sure, the reaction to rising acidity isn't the same with all species. Researchers at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) subjected 18 species of shellfish to varying degrees of CO2-induced acidity in seawater in special tanks. They exposed the water to varying levels of CO2, selected from among the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's emissions scenarios. Unexpectedly seven species, including lobsters, shrimp, and clams, actually built thicker shells.

“Some organisms were very sensitive,” Anne Cohen, a researcher at WHOI who took part in the study, said. "But there were a couple that didn’t respond to CO2 or didn’t respond till it was sky-high – about 2,800 parts per million. We’re not expecting to see that anytime soon.” One of the seven stoics was coral.

The team cautions that the animals were well fed and were not subject to any other environmental stresses. So the results don't shed much light on the synergystic effects acidification might have on the seven survivors. That's for another round of experiments. Still, “we can’t assume that elevated CO2 causes a proportionate decline in calcification of all calcifying organisms,” says Cohen.

No complex computer models here

The science behind the ocean acidification process is far more straightforward than climate science – needing little more than a high-school grasp of chemistry to understand, says Richard Feeley, a researchers at NOAA's Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle, Wash.

He says that the oceans are soaking up CO2 at a rate that matches the rate at which atmospheric CO2 concentrations are rising. The link between rising human emissions and rising uptake is unequivocal, he says, adding that the ocean is growing acidic at a pace 100 times faster than at any time in at least 20 million years. And no matter which ocean researchers examine, "we get the same changes everywhere we look," he says.

While the basic mechanism is easy to grasp, scientists are finding it more difficult to determine the long-term biological effects. Much depends on the animals involved, as well as natural cycles of ocean circulation that bring carbonate-poor waters to the surface.

Scientists in Australia, for instance, have projected that rising acidity may start eating into populations of tiny plankton in the Southern Ocean far sooner than previously believed. The reason: natural upwellings of carbonate-poor water combines with acidification to deprive the creatures of carbonates at a critical time in their development. They had adapted to deal with upwelling part of the equation. But they are unprepared to handle the additional reduction in carbonate caused by the industrial CO2 being added to the oceans.

Others have found evidence of shellfish losing their ability to grip rocks in increasingly acidic waters, as well as signs of shell erosion.

Filmmaker Sven Husbey, who along with his wife produced a documentary on the subject, says that as they've toured the world showing the film they have won converts. Many of the viewers are self-described skeptics about global warming. Yet "again and again and again, they get ocean acidification," he says. "Even if we could cope with global warming without reducing emissions, we would still lose the oceans."

------------------