The genealogy of a stateless family – and the need to become a citizen

Loading...

| Batey 43, Dominican Republic

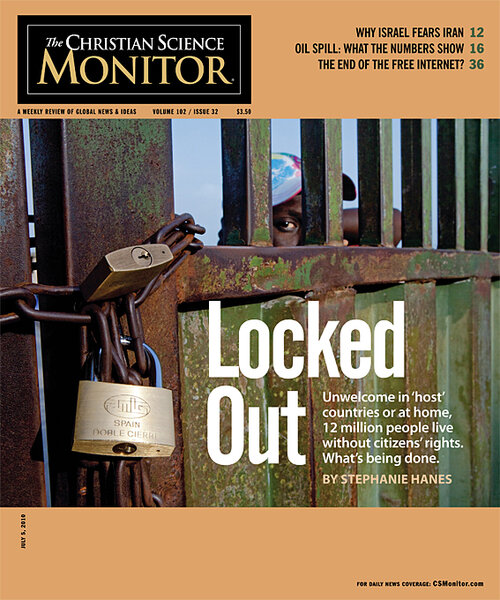

The story of the Jean family shows the genealogy of statelessness on the Caribbean island, Hispanola, shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic. It's repeated tens of thousands of times, in different variations. And it is causing increasing tension in the bateyes, or old Dominican sugar cane plantations, where many Haitian descendents still live.

Andre Jean, now 73, came in 1956 across this Michigan-size island of Hispaniola to the Dominican Republic from his home country, Haiti, to cut cane – part of a wave of Haitian sugar cane workers invited by the government of Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo. Sugar was the country's big business back then, and it needed labor. Haiti, led by its own dictator, was happy to oblige.

"Trujillo sent the trucks to pick us up," says Mr. Jean, who ended up at this sugar plantation, 27 miles outside the capital, Santo Domingo. He cut cane for decades, a brutally hot and physically demanding job. And he has never left.The sugar industry has declined dramatically – but every day Jean still walks to the fields with his machete, to earn some change cutting weeds.

His Haitian wife has died, but his five surviving children, all born here, still live nearby. He shows off some of their diplomas, which hang on the walls of his small, well-kept peach-colored house.

Those children grew up speaking both Spanish and Creole, but graduated from Dominican schools, and many got jobs in the Dominican public sector. Two of his sons were police officers – one died clearing roads for the Dominican president's motorcade. His children were never told that they were not Dominican, says Maria Camilise, Jean's 43-year-old daughter.

But statelessness has affected the next generation, in large part because of changing Dominican laws.

Jean's 22-year-old granddaughter, Sonia Mide Camilise, grew up even more Dominican than her aunts and uncles. But she cannot go to college because the state tells her she is Haitian. She says that everyone in her graduating class who lives in her batey neighborhood is in the same predicament. Many of Jean's other grandchildren have also had problems with documents.

The family wonders what will happen to this generation.

"It hurts me," Jean says. "It is not right."

• Travel for this article was funded by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.