Nuclear weapons: Is full disarmament possible?

Loading...

| Paris, Berlin, Washington, and San Francisco

The dew had barely dissipated from Barack Obama's inaugural as the four senior men slipped into the Oval Office. The executive precincts were intimately familiar to all four – former Secretaries of State George Shultz and Henry Kissinger, former Sen. Sam Nunn, and former Defense Secretary William Perry.

Mr. Obama's national security adviser, Gen. Jim Jones, and his chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel, were in the room. But they didn't say a word. The president engaged the four men on his own. The topic was a project to eliminate nuclear weapons, which the elder statesmen feel ardently about.

But they didn't have to do much convincing. Obama was already there, ready to carry the nuclear-free torch as Presidents Kennedy and Reagan had before him.

"He told us this was one of the top four objectives of his presidency," Mr. Shultz recalls of the meeting. "He said, 'Let's see if we can do something about this....' He conducted the conversation entirely on his side."

A month earlier, Obama had journeyed to Hradcany Square in Prague, Czech Republic, and boldly declared plans for a nuclear-free world. "I state clearly and with conviction America's commitment to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons," Obama said. Gasps ricocheted through some world capitals. The announcement, coming after several days of Obamamania in Europe, including back pats between the first lady and the Queen of England, was unexpected, even jarring. Realists immediately argued that banishing nukes seemed naive or flaky, premature, an overdose of American-style idealism.

Yet since the halcyon words in Prague, in a world of protracted wars and tragic trivial pursuits, some of the most arch realists in the US foreign-policy establishment are buttressing the concept of a nuclear-free world.

A senior generation of "wise persons," who are not surfing peaceniks living in vans but who spent their lives as high-ranking cold warriors, have quietly advocated a world of zero nukes since 2007. They include figures like Colin Powell, John McCain, and Madeleine Albright, and 17 of the past 22 secretaries of Defense, as well as former national security advisers. Most prominent is the "gang of four" – Messrs. Schultz, Kissinger, Nunn, and Perry – who met that day with the president in the Oval Office.

Behind the push is the sobering realization of how dangerous the world has become. During the last great public debate over nuclear weapons – in the 1980s – the world had good reason to be wary: Two adversaries with huge nuclear-tipped arsenals, the US and the Soviet Union, were confronting each other around the world in a fraught game of geopolitics.

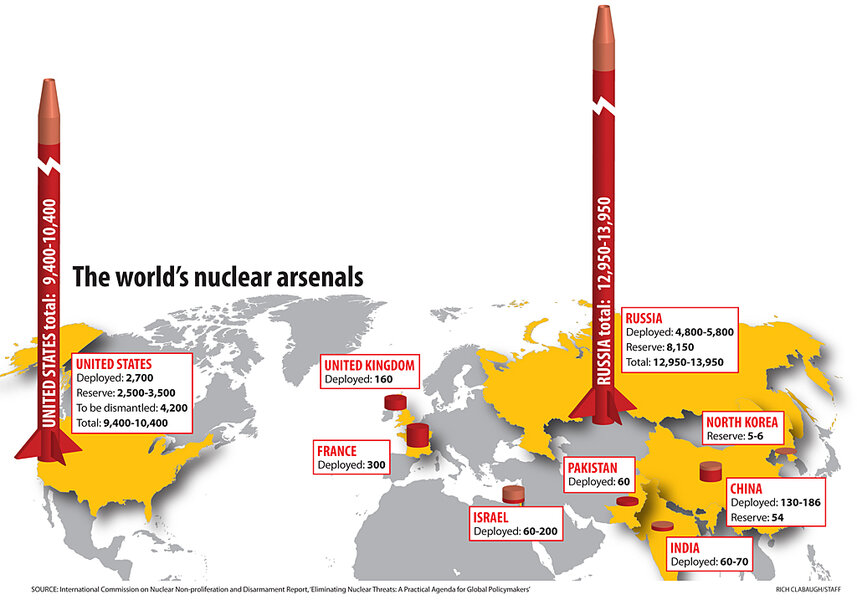

Today, in the aftermath of the cold war, the old threat has greatly diminished. The two countries maintain smaller but still potent nuclear stockpiles. Yet other threats now loom: the expansion of the nuclear club to include rivals like India and Pakistan as well as mercurial North Korea; the quest to join by new states like Iran and Syria; the possibility of nukes finding their way to terror groups that could use them – in Moscow, the Middle East, Beijing, or Washington.

"Why is it so hard for us to solve a problem that is obvious?" Schultz asked with an edge of exasperation in an interview at his home in California.

Skeptics of a nuclear-free world might answer that such a goal is politically impossible and practically dangerous: They believe it could lead to an even greater possibility of a nuke being used.

As Obama prepares to host more than 40 world leaders April 12 in Washington to discuss the spread of nuclear materials, this will be the fundamental question underlying it all: Is a nuclear-free world actually attainable? Is it just a gauzy notion, or the grand imperative of our time?

* * *

Whatever the different views, the issue is once again being discussed somewhere other than in the cubicles of a few think tanks. It is, at least rhetorically, a stated US goal.

In the Oval Office meeting with Obama, Schultz bantered a bit with the president about the politics of the issue. Obama told Schultz, who was present with Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev at the historic first cut in nuclear arsenals in 1986 in Reykjavik, Iceland, that it was nice to work on a bipartisan issue. Schultz told Obama the issue is "obviously bipartisan," but added, "none of us think of it that way.... It is nonpartisan. It is a subject of such importance that it ought to be taken out of any partisan arena." Schultz says that "Obama laughed and agreed."

Two weeks ago when Obama announced the new START treaty as part of a US "reset" with Russia – a small but crucial hurdle in moving forward on a larger nuclear agenda – he thanked and named each of the "gang of four" statesmen.

The four men are fond of using the word "urgent" in arguing for zero nukes. They worry less about a cold-war nuclear missile exchange, and more about jihadists seizing fissile material from, say, an unstable Pakistan, which has of late continued to produce more highly enriched uranium than it needs. Or a possible Middle East nuclear race by Egypt, Syria, or Saudi Arabia in the wake of a bomb made by the Shiite government in Iran. (This is to say nothing of what Israel's reaction might be.)

Yet Nunn and others say the dangers also encompass the possibility of human errors and mistakes by the traditional nuclear powers. US and Russian missiles, for instance, remain on a five-minute "quick launch" timetable, which Nunn calls a situation "bordering on insanity." Plus, as nations turn more to nuclear power as an answer to global energy needs, there will be an exponential increase in the reprocessing of plutonium or uranium, which can be used in making a bomb.

The post-cold-war era has brought the expansion of a global middle class and the comforts of Starbucks, iPods, Facebook, and nonstop sports, weather, and food channels. But the legacy of 20th-century nuclear science hasn't ended, the four say, even if it's often ignored or forgotten.

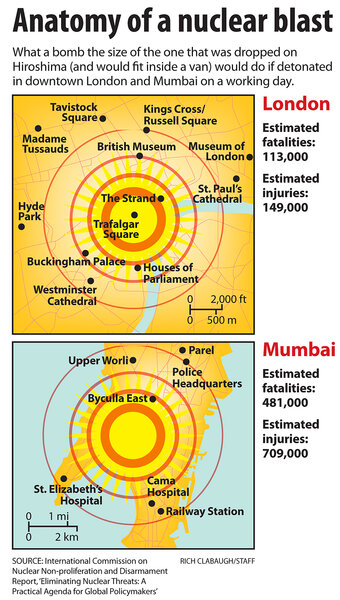

At the American Academy in Berlin this winter, the gang met with four German "wise men," including former Chancellor Helmut Schmidt and former President Richard von Weizsäcker. They cited a new study comparing what would happen if a weapon the size of the one dropped on Hiroshima was placed secretly in London and in downtown Mumbai (Bombay).

The study, by former Foreign Ministers Gareth Evans and Yoriko Kawaguchi (of Australia and Japan, respectively), says that a weapon detonated from inside the back of a large van in London's Trafalgar Square in the middle of a workday would cause an estimated 115,000 fatalities and another 149,000 injuries from a combination of blast, fire, and radiation poisoning; detonated in population-dense central Mumbai, the figures would be more like 481,000 fatalities and 709,000 injuries.

"The danger today is know-how, materials, and weapons gradually spreading," says Richard Burt, part of the US team in Reykjavik, who now advises the international advocacy group Global Zero in Washington. "Some groups would like to get a bomb and use it. What's fundamentally different now is Pakistan, where weapons are held by a state that is in the middle of an insurgency by Islamic extremists. We didn't have that before."

For the White House and the gang of four, the basic steps needed to reduce the threat of possible nuclear catastrophe include:

•Reducing current nuclear stockpiles;

•Locking down known fissile material and attendant technology;

•Convincing other nations not to move outside the nonproliferation regime, the central international treaty of the cold war, now widely described as "fraying" or worse.

Those steps have more than rhetorical urgency. In April and May, the White House takes up all three issues in what US officials describe as an effort to create needed momentum and overcome substantial inertia and doubt.

The new START treaty, which was scheduled to be signed by Obama and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev in Prague on April 8, reduces strategic nuclear warheads by about 40 percent, from 2,700 to 1,550 on each side, and halves the number of launchers. (In the 1980s, the two sides had roughly 20,000 warheads.) It will then need to be ratified by two-thirds of the US Senate.

Trying to build on the START momentum, the White House hopes to forge an agreement to contain plutonium and uranium at the April 12 fissile materials summit in Washington.

"We need to get lots of countries to adopt very strong physical protection measures," says a senior US official. "This would secure and lock down all materials in four years. It is a big ask for us in [dealing with nuclear] smuggling and screening cargo ships. We get the buy-in if we do our part."

Part of the fissile material safeguards discussion may involve a global nuclear fuel bank. It would loan states that want to generate nuclear power the uranium they need to fuel civilian reactors – eliminating the enrichment process that allows them to create weapons-grade material.

In May comes the review of the Non-Proliferation Treaty – the gemstone of disarmament, dating to the 1960s. It sets international standards making it difficult for states to go nuclear, based on a trade-off with existing nuclear states that they will continue to reduce their stockpiles. Yet with North Korea believed to have enough material for several bombs, and with Western intelligence indicating that Iran is further along with its nuclear program than previously assumed, many consider the NPT weak.

"This NPT can be a defining moment, in a positive or negative way," says Corentin Brustlein at the French Institute of International Relations in Paris. "It can confirm and renew moves toward disarmament and proliferation. Or it can be a moment where it loses its credibility, because no one believes it and states will seek a nuclear option."

How to enforce compliance on NPT is critical. But if the White House can build on the momentum of START, a successful NPT could create international pressure on states that have or want to "break out" of international controls, most notably Iran.

* * *

The road to zero, however, faces a silo of skepticism, inertia, and practical and psychological complexities. Current nuclear security umbrellas provide protection to states like Japan and Poland, which aren't ready to have their safeguards abandoned.

States like India and others see nuclear status as a matter of prestige. China isn't yet ready for disarmament. Smaller states view nuclear weapons as a hedge against large states with hefty conventional armies. Nor are Pentagon strategists dancing in their bunkered hallways about zero nukes.

Some analysts argue that if nukes are outlawed then only outlaws will have nukes – the nations that don't conform to international treaties. "The American nuclear arsenal doesn't encourage local arms races; it forestalls them," writes Ross Douthat, a New York Times columnist."

Sen. John Kerry, though a supporter of no nukes, notes that you can't get to zero unless everyone goes there. "The road to zero does not run through a nuclear Iran," he says.

Former US Defense Secretary William Cohen, speaking with the Monitor at the Munich (Germany)Security Conference, says a nuclear-free world is a difficult idea that needs support. But in the current world environment, he doesn't see it happening anytime soon. "Zero is a concept that is desirable as a global initiative," Mr. Cohen says. "Is it feasible? I doubt it. Is it verifiable? I'm not sure. Plus, Israel is never going to say, 'We're OK with that now.' "

And if one country isn't OK with that, others may not be either. Francis Gavin, director of the international security program at the University of Texas, Austin, notes that Iran, for one, is hardly irrational in wanting to develop nuclear weapons. In its region alone, Tehran looks around and sees that Pakistan, India, and, yes, Israel have nukes. "If a state feels under threat," he says, "a treaty isn't going to help."

In a world of outlier states, fashioning effective international controls becomes difficult. David Albright at the Institute for Science and International Security in Washington, D.C., believes that Iran and North Korea are now "sucking the air out of the room politically" on the treaty issue. "But the biggest problem anyway is not a treaty, but illicit trade," he says.

Still, no one is suggesting the world go to zero nukes next week. The point for proponents may be just to get the conveyor belt moving. Russian Deputy Prime Minister Sergei Ivanov said as much last February in Munich, noting: "Do I believe in global zero? Not in my lifetime. But if we don't start, never in the lifetime of my grandchildren."

Further, proponents of nuclear reduction note that political will is always a problem. Their concern is that weapons of mass destruction have become like nuclear wallpaper – so accepted in daily life and security that they no longer seem a threat, but are simply part of the décor, part of stability.

Meanwhile, proliferation is set to increase due to boosts in civil nuclear programs and the black art of illicit nuclear trade. A key worry is that the highly conscious disciplines of a cold-war generation – the nuclear safeguards, the cares and customs and unwritten codes of deterrence – are far less rigorous today. Nukes are treated almost casually.

* * *

At his home in Stanford, Calif., Schultz worries about precisely this – human obtuseness on such a life-and-death issue. The Non-Proliferation Treaty is "unraveling because there hasn't been significant commitment on the part of countries that have nuclear weapons to get rid of them," he says. "We haven't had a calamity. But do we have to wait for one ... before it is a problem?

"If a nuclear weapon went off in Bombay or Myanmar, somewhere, anywhere, Peking or Paris – we would all get up and say we have to do something about this. Get rid of these weapons! Why can't we do something before it happens?"

Schultz was weaned in an era of thinking the unthinkable – a thermonuclear exchange that would destroy the US, Europe, and the Soviet Union. During World War II, he was a US Marine on a ship headed for San Diego, with men who had all fought in the Pacific, to prepare for the invasion of Japan, when he first heard about the atom bomb.

Later, he went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology on the GI Bill. It was an era, post-Holocaust, where leading thinkers – physicists like Robert Oppenheimer and Albert Einstein, and public intellectuals like Harvard president James Bryant Conant and sociologist David Riesman – wrestled with the moral and ethical dimensions of modern science. Many argued that nuclear technology was a leap so advanced that humans would be unable to restrain their baser instincts in the pursuit of power.

Yet it wasn't until Schultz became secretary of State that he focused on the nuclear issue. President Reagan also came to feel that "mutually assured destruction" was folly. But the idea of a nuclear-free world at the time seemed incredible, "really shocking," Schultz says.

After the Reykjavik summit, which nearly eliminated US-Soviet stockpiles, Schultz came back to Washington and was "beaten up" by British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher at the British ambassador's residence.

"She said," Schultz remembers, " 'How could you sit there and allow the president to do away with nuclear weapons?... You are supposed to be the one with his feet on the ground.' "

" 'But, Margaret, I agreed with him,' " Schultz answered. "Her reaction was typical – this was a horrible idea."

(Reagan later told Congress the US would seek "the total elimination one day of nuclear weapons from the face of the earth.")

The four statesmen's initiative dates partly to a conference Schultz and Stanford physicist Sidney Drell held in 2007 on the 20th anniversary of Reykjavik. At the time, no one was paying attention to nukes, Schultz says, though no one any longer thought nuclear reduction a horrible idea. "If you asked three years ago if we would be where we are today on progress in raising the nuclear issue, I'd say you were out of your mind. But it is also true a lot of work needs to be done."

Some of the further work may require political fights on questions like a US ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. The treaty bans the underground tests that states use to develop a nuclear capability or refine their arsenals. Many states, like France, have already signed the CTBT, but the US, saying it doesn't want to abandon nuclear research and development, has not.

On the zero-nukes issue, too, some European analysts see the US acting in its own self-interest. "The US may be totally sincere in proposing a nuclear-free world," says Mr. Brustlein of the French Institute of International Relations. "But they can do so because of conventional superiority. The US knows that nukes are the main means for others to contain its military superiority. Nuclear weapons strike a balance between unequal actors."

He cites India's former Chief of Army Staff Krishnaswamy Sundarji, who, after the US's quick victory in the first Gulf War, said the main lesson of that conflict is to never fight the US without nuclear weapons.

* * *

As with any debate about weapons of mass destruction, one issue is how big a megaphone to use in warning of the dangers they pose. Dr. Gavin of the University of Texas believes some zero-nuke advocates have become too "alarmist," which, he says, can make the world less stable by encouraging nations, particularly the US, to drift toward preemptive war policies.

But others, including Barry Blechman, cofounder of the Henry L. Stimson Center in Washington, D.C., say the threats warrant a clear and serious warning. Nuclear disarmament, once dismissed as the playground of a few Cassandras and Don Quixotes, is now a mainstream position. Advocates used to be "marginalized," he says. "Now we are seen as normal."

Schultz, who has witnessed the menace and machinations surrounding nuclear weapons since the atom was first split, counsels taking a slow and steady approach in getting to zero. But he believes the goal is achievable – and imperative. To those who think it isn't, he summons the lessons of history.

"Few in the early '80s imagined the political changes that would in a few years result in the peaceful end of the cold war," he said at a conference in Oslo in 2008, as cited in the book "Abolishing Nuclear Weapons." "Similarly today, we underestimate the potential for developments that would profoundly change the prospects for abolishing nuclear weapons."

He added: "If a few leaders of nuclear-armed states stepped forward with conviction ... to seek the prohibition of nuclear weapons, many obstacles that seem immovable today might become movable."