Next prime minister’s challenge: Regaining Britons’ trust

Loading...

| London

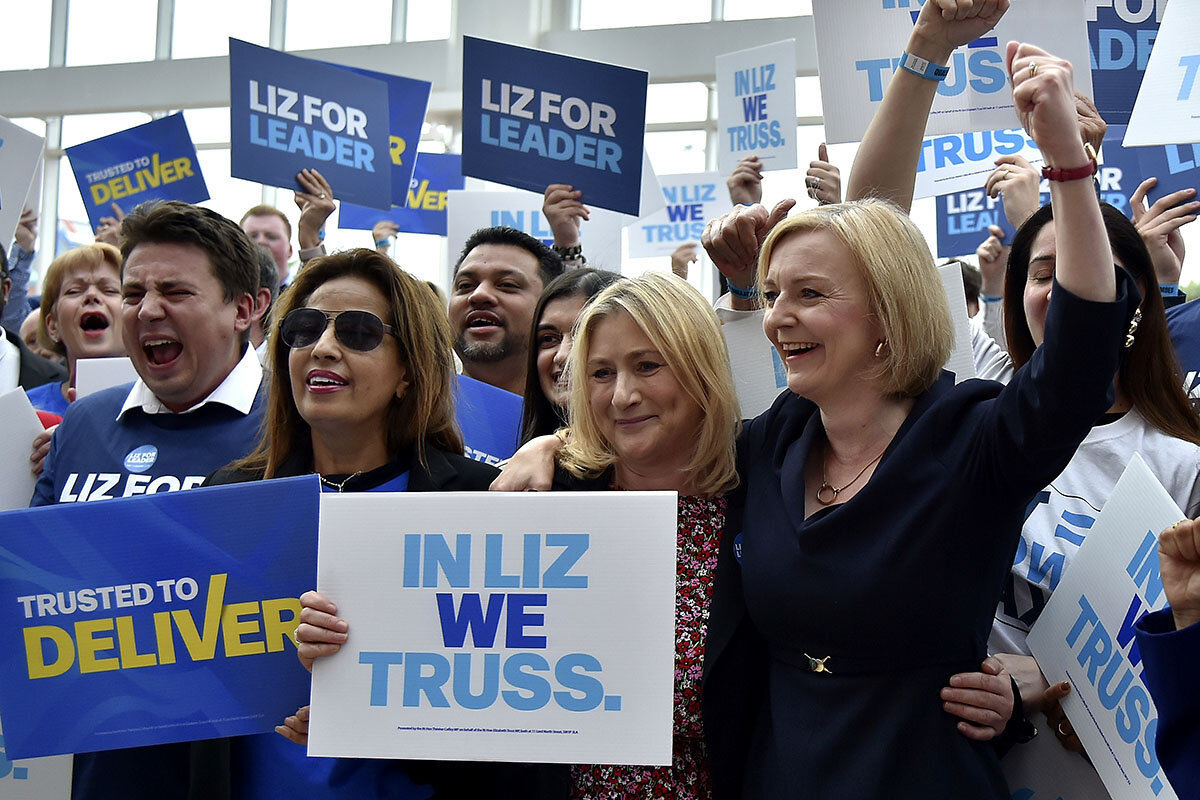

None but the most hardhearted critics of British Prime Minister Liz Truss could have wished on her the manner of her departure: a terse, humiliating resignation statement on Thursday in front of the famous door of No. 10 Downing St. – almost exactly 24 hours after telling Parliament, “I’m a fighter, and not a quitter!”

But if her personal agony is drawing to an end, her departure next week will leave her ruling Conservative Party – and the country – facing a political challenge with no obvious, early resolution.

The Conservatives’ immediate task is daunting enough – to settle on an agreed successor. Never in the party’s recent history has it been so riven by personal and ideological rivalries.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onThe deeper challenge facing Britain has less to do with the fortunes of individual politicians – or even one party – than the health of Britain’s democracy, and the sense of connection between the politicians and those they’re elected to serve.

Yet the deeper challenge lies beyond the Westminster bubble. And it’s best understood by looking not at how Ms. Truss’ tenure is ending, but at how it began.

Not at what her departure means for individual politicians, but what it means for the health of Britain’s democracy, and the sense of connection between the politicians and those they’re elected to serve.

Ms. Truss took office in early September following her traditional audience with the British monarch, in what turned out to be Queen Elizabeth II’s last public engagement.

As Ms. Truss settled into Downing Street, the country came together in an extraordinary outpouring of grief, admiration, appreciation, and respect for the late queen – a demonstration of a gentle, caring, unifying sense of community vanishingly rare in most 21st-century democracies.

The test now for Britain’s Conservatives will be to find some way of tapping into that reservoir of community, to reconnect – after a dozen years in power under four different prime ministers – with voters increasingly mistrustful not just of the party, but the institutions of government.

Ms. Truss’ six weeks in power, the shortest tenure of any British prime minister, have made such a reconnection both more urgent and more difficult.

By launching a new economic policy with tax cuts for business and wealthy individuals funded by billions of pounds’ worth of additional government debt, she unsettled the financial markets. The result was to push mortgage rates and inflation higher, and drive down the value of the British pound. With the economic effects of the war in Ukraine already squeezing family budgets, her government suddenly made things worse.

Yet the sense of grassroots alienation her successor will have to address goes beyond economic issues.

It’s rooted in a profound change in the Conservative Party since the 2016 referendum that ended Britain’s decadeslong membership of the European Union.

The Conservative prime minister at the time, David Cameron, wanted to stay in the EU. So did most of the party’s members of Parliament. But from that point on, a party that had dominated British politics for decades with a mix of traditional center-right policies and pragmatism made a single ideological issue, Brexit, a litmus test for advancement.

Mr. Cameron’s successor, Theresa May, had backed staying in the EU. So had Ms. Truss. But both became prime minister as converts to Brexit. The leader who Ms. Truss succeeded, Boris Johnson, was not only a Brexit backer, but also the leader of the campaign to leave the EU.

The Brexit issue itself hasn’t necessarily hurt the Conservatives. Like former President Donald Trump’s appeal to working-class voters in America, Mr. Johnson used Brexit’s populist “take back control” appeal to capture constituencies long held by the opposition Labour Party in a landslide election victory three years ago.

What has eroded the connection with voters has been a more general sense that a narrowly focused ideological fixation on Brexit has become almost a Conservative parlor game in Westminster, crowding out concern for the real-life needs and priorities of voters.

Mr. Johnson was forced out of office this summer by a similar kind of remoteness: He broke the pandemic rules he had imposed on the rest of the country by partying in Downing Street. For Ms. Truss, it was her ultimately harmful “post-Brexit” economic plan – rooted in a vision of buccaneering Britain, freed from European rules and regulations, outgrowing its former partners.

Whoever now takes over – and there have been reports that Mr. Johnson himself is contemplating a comeback – will now have to reckon with polls that give the long-struggling Labour Party a lead of more than 30 percentage points.

The new prime minister may get a slight bump in the polls. But since he or she will be the second successive prime minister to be chosen by the ruling party, not by British voters, they will be under strong pressure to call fresh elections.

That’s why the need to reconnect with voters will matter at least as much as the identity of the next party leader, or even any specific policies.

Ultimately, what will matter is not how the Conservatives or the Labour Party lead Britain over the next few years.

It goes deeper. Can either party somehow animate and nurture the sense of community so dramatically brought to the surface by the response of millions of Britons to the passing of a 96-year-old monarch almost none of them had ever met?