Britain’s hedgehogs are in a prickly situation. Meet their rescuers.

Loading...

| Sheffield, England

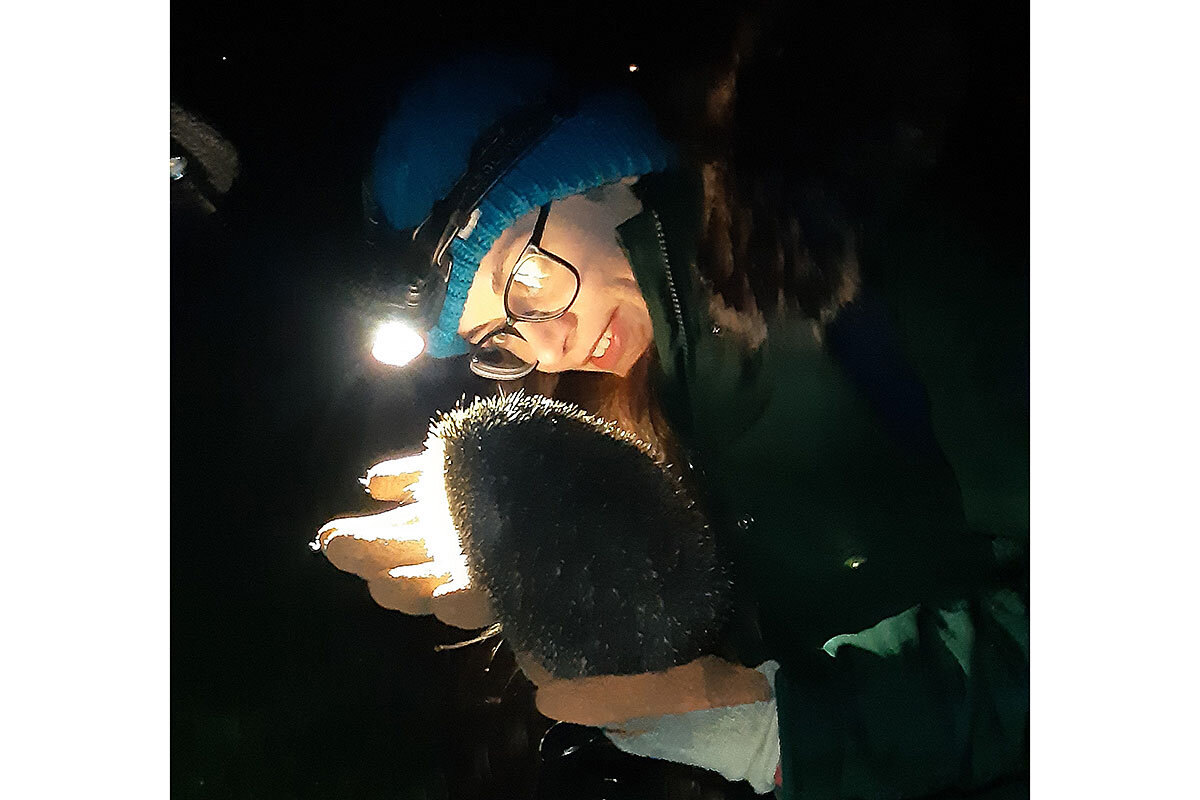

Jo Wilkinson realized she was losing her students’ attention, so she turned to an old friend: the hedgehog.

As a sustainability and engagement officer at Britain’s University of Sheffield, she wanted to rally students around sustainable foods and energy conservation. But it could be hard to hold students’ interest. That was until she proposed building a “hedgehog safari” trail on campus. Soon, her fun distraction became a campuswide campaign.

“I recognized straightaway that hedgehogs captured everyone’s imagination,” says Ms. Wilkinson. “There’s something about them that does that to people.”

Why We Wrote This

Britain loves its hedgehogs, but as their habitat is developed over, their numbers are dwindling. Fortunately, hedgehog lovers across the country are finding ways to make life better for the tiny garden dwellers.

Her effort to expand hedgehog habitats at Sheffield earned British Hedgehog Preservation Society (BHPS) funding in 2019. That’s when she started thinking about how she could help hedgehogs thrive at university campuses across the United Kingdom. Within 18 months, she had a fully funded national project that has certified 110 “hedgehog-friendly” campuses across the country.

“I’ve always dreamt of a job where I’m passionate about what I’m doing. There’s nothing in the world I’m more passionate about,” says Ms. Wilkinson. “Campaigns to save hedgehogs are all about the joy volunteers are getting.”

An icon under siege

Britain’s hedgehogs need all the help they can get. The country’s “red lists” categorize species based on how threatened they are. Hedgehogs joined the lists in 2020, officially classified as vulnerable to extinction. But advocates and organizations like Ms. Wilkinson and BHPS, which maintains her Hedgehog Friendly Campus accreditation program, are working to save the iconic British garden dweller.

Researchers estimate there were about 1.5 million hedgehogs across England, Scotland, and Wales collectively in the mid-1990s. The population size is difficult to keep track of, but studies show that British hedgehog numbers in rural areas have declined by 50% since 2000, though in cities and towns the decline is closer to 30%.

“It’s almost as if hedgehogs are moving out and doing the opposite of humans,” says Ms. Wilkinson. “They’re moving into towns and cities because perhaps those places are providing them a bit of a refuge.”

Hedgehogs tend to follow people, she says, and have found that they can scavenge on cat and dog food in gardens. Compared with the countryside, urban areas can offer “places of refuge where they’re less exposed,” she says.

That’s become more valuable as rural areas have lost wildflowers, bramble patches, and leaf and log piles in the countryside. Pesticides from intensive, modern farming practices and “habitat fragmentation” – the “chopping up” of Britain’s landscape into smaller pieces – have added to the rural challenges facing hedgehogs, says Hugh Warwick, author of four books dedicated to the spiky critters.

The self-dubbed hedgehog connoisseur leads the fight in finding solutions to the destruction of hedgehog habitats due to “manicured gardens.” From his garden shed in Oxford, Mr. Warwick has drummed up over a million signatures for a petition calling for British planning law requiring all new developments to include “hedgehog highways”: holes to allow hedgehogs to move freely between gardens.

Mr. Warwick – once described by a British politician as the “Lorax of hedgehogs” in reference to Dr. Seuss’ literary character who “speaks for the trees” and fights suburban development – has managed to convince the government to change planning law guidance through his petition and online campaigning. “But I want more. I want it to be set in stone, to be not just a ‘nice to have’ but a ‘must have.’”

Bovis Homes and Taylor Wimpey, two of Britain’s biggest house-building companies, have already signed onto the idea of incorporating hedgehog highways because of its popularity.

“Businesses are ignoring what’s coming from the government; they’re doing it themselves because it’s the right thing to do,” says Mr. Warwick.

The nearby hamlet of Kirtlington has already devised a hedgehog highway featuring eccentric holes, miniature stairs, and knocked-down walls that knit gardens together. Villagers took a map of the hamlet and spent time working out the minimum number of holes to connect a maximum number of gardens. A map of the hedgehog highway helps tourists trace the paths of the tiny inhabitants.

“The communities have banded together to connect it to hedgehogs, and each other,” says Mr. Warwick.

Remaking the landscape

Recognizing the threat toward one of the U.K.’s favorite creatures is an opportunity for people to reconnect with their surroundings.

For Ryan Wallace, sustainability officer at the University of London, which is part of the Hedgehog Friendly Campus initiative, that means ensuring hedgehogs thrive in the most unlikely of places: central London. Though surrounded by Regency-era houses and within walking distance of busy tourist attractions, the public squares of Bloomsbury offer overgrown bushes and ample foliage. That makes them – and the neighboring university – fertile ground for hedgehogs, though none were seen last year.

“They can travel up to 2 miles through the streets of London,” says Mr. Wallace, pointing to the thin, black Victorian-era fences that they scuttle through at night. “Hedgehogs have loads of benefits people don’t realize. They keep the slug population down, and they’re natural pest killers,” he says. They’re also a good indicator of how well the natural environment is doing.

Rewilding green spaces can give hedgehogs a better chance of thriving. “If there’s a space in your garden where you can let the weeds grow, do that and stop cutting the grass,” says Ms. Wilkinson. “Let nature be nature.” Convincing university gardeners and grounds staff to avoid pulling brambles or mowing grass can be tricky. “The easiest sell for them is that it’s less work!” she says.

Greenery isn’t so hard to come by 125 miles away, in the green spaces of Nottingham Trent University, a “bronze-winning” Hedgehog Friendly Campus. Wildflowers, ponds that collect rainwater that washes off of student housing, and a nature trail surround the Clifton campus, 4 miles from Nottingham city center.

Sarah Robertson, the school’s sustainable development projects officer, has plans to add special hedgehog accommodations like ramps to provide safe exit from ponds. “They can swim really well, but they get tired,” she says. “If they can’t climb out, they’ll get into trouble.”

She wants to get individuals thinking “beyond their comfort zones” by asking construction services to incorporate the right plants and convincing sports teams to lift netting to ensure hedgehogs don’t get caught up.

For many advocates, hedgehog conservation isn’t just about the survival of a species. It’s a chance to connect with bigger environmental issues such as climate change.

“You can start with hedgehogs, because that doesn’t scare people off. Everybody has an anecdote about a hedgehog. That can provide a springboard into the most serious ecological conversations,” says Mr. Warwick. “There’s that capacity to bring people together because it’s an animal that doesn’t provoke a negative response.”

Ms. Wilkinson agrees, pulled not just by the science, but by the emotional lure of hedgehogs.

“They are ridiculously cute. That’s the basis of it.”