Russia looks for US to propose 'bigger, better' arms control

Loading...

| Moscow

It’s become something of a signature play by the Trump administration to reject or tear down an existing framework of agreements, then pledge to replace it with something much, much better.

Russian security experts, who have attentively watched recent United States approaches to North Korea and Iran, among others, are wondering about Washington’s apparently newfound priority for “arms control.” Is Russia about to be offered a whole new deal, in an area that is traditionally of huge importance to Moscow?

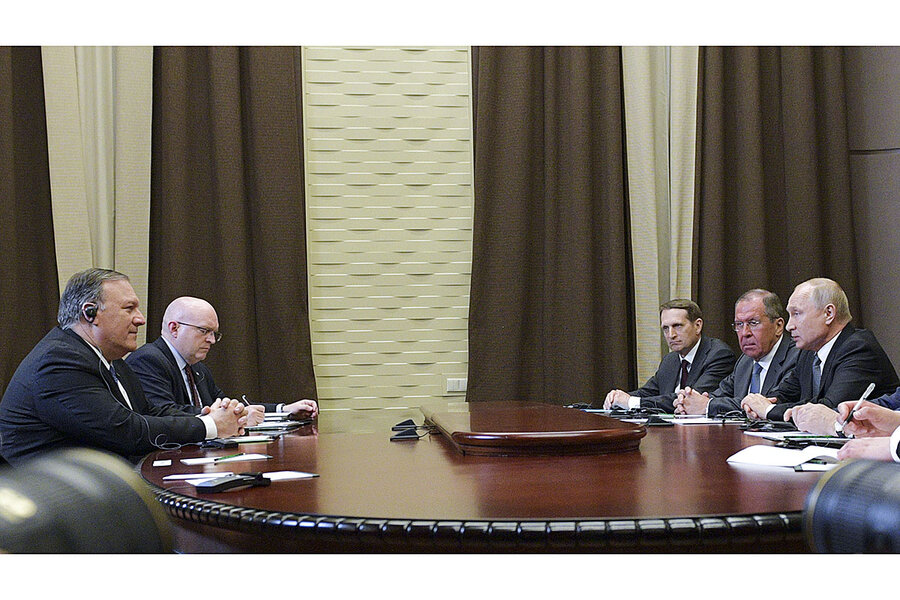

It’s a bit of a head-scratcher because no details have been offered by either the White House or the Kremlin following President Vladimir Putin’s meeting in Sochi with U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo last week. And the return to talk of arms deals comes only a few months since many started declaring the half-century-old paradigm of U.S.-Russia nuclear arms control all but dead.

Why We Wrote This

With the end of the INF treaty this year and the New START treaty set to expire soon, Russians are anxious to establish a new arms control regime with the U.S. But they are still waiting for the Trump administration to make an offer.

Earlier this year the U.S. pulled out of the landmark Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty, which banned a whole class of nuclear missiles as the Cold War was ending, and Russia followed suit. No one thinks the agreement can be revived. The last remaining strategic arms accord, the New START treaty signed almost a decade ago, expires in less than two years, and no negotiations to extend it are yet on the horizon.

Like many ideas put out by the Trump administration, the fresh talk of arms control might mean almost anything. Analysts say it might just be a distraction, to introduce an upbeat note into an agenda loaded with issues that Russia and the U.S. bitterly disagree about, like Iran and Venezuela. But there might just be a new and bigger concept coming out of Washington, one that Russia could be willing to discuss, some analysts say.

“The Americans have signaled a willingness to talk about more general principles of strategic stability rather than counting missiles and warheads,” says Andrey Kortunov, director of the Russian International Affairs Council, which is affiliated with the Foreign Ministry. “That would be issues like militarization of space, and artificial intelligence, and other things that might destabilize the situation. It’s not about reduction of arms, but reduction of risk. We do believe that the U.S. needs arms control in some form; that there is a consensus that it strengthens national security can be verified with Russia, and serves to promote stability.”

Mr. Kortunov says he had a chat with U.S. national security adviser John Bolton last year, at a breakfast meeting in the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, in which Mr. Bolton strongly suggested that the Trump administration wants to leave an imprint on nuclear arms control that would distinguish it from its predecessors.

“Bolton said that all these existing deals are too small and narrow, and that we need to come up with something big – a new principle of strategic stability,” Mr. Kortunov says. “One of the ambitions they might have is to do something that would put Trump in a whole different league from Obama. It’s not at all clear what that means for us. But would Russia be willing to talk about it? Probably. We’ve had a lot of disappointments with Trump in the past few years, and it’s a big question for us whether he can deliver anything he talks about. But maybe at least we could hope for some kind of confrontation management.”

Both the U.S. and Russia are in the midst of sweeping modernization of their nuclear deterrent forces, and neither would probably be willing to cut their arsenals below the levels stipulated in the New START treaty, say experts.

One complaint the U.S. has raised about the old framework of arms control is that it is bilateral and does not include new nuclear missile powers like China. Even though the U.S. and Russia still possess over 90 percent of all existing nuclear weapons, it’s a legitimate point, analysts say.

“It may be possible to prolong the New START treaty, but do we really need it in its present bilateral form?” asks Pavel Zolotaryov, deputy director of the Institute for U.S. and Canada Studies in Moscow, which is part of the Russian Academy of Sciences. He says the old deterrence framework of mutual assured destruction still works, but it is fast being eroded by the emergence of new powers. The issue facing the U.S. and Russia now is how best to expand the arms control framework to include these new countries.

“It doesn’t look likely that China and other countries will agree to join the process now, but the sooner the U.S. and Russia prolong the treaty we have, the sooner we can move on to finding ways to bring in others,” Mr. Zolotaryov says. “It’s becoming urgent to solve these new questions about nuclear deterrence, to minimize the risk that nuclear weapons will be used.”

Fyodor Lukyanov, editor of Russia in Global Affairs, a leading Moscow-based foreign policy journal, says that more than two years of dealing with the mercurial and contradictory style of the Trump administration have left Russia’s foreign policy community bemused and divided over whether to try to deal with it, or just wait it out.

“Some people are saying we really need arms control, because it’s the only way to avoid a ruinous arms race. Others say there is nothing we can get from the U.S. at this point, so why bother? The only practical thing we really have to talk about is extending New START. That would be a cheap and easy way to create the impression of activity,” he says.

“But it’s a strange picture. Despite the fact that our relations over the past three years have been a disaster, there are many people who hear Trump saying positive things [about relations with Russia] and seeming to resist the people who embody the old approaches, and it makes him look good to some Russian commentators. Apparently that includes Putin. In spite of everything, there is this feeling that Trump is different, that he is the guy to tear down this post-Cold War system,” he says. “So, if he invites Russia to dance one more time, we will probably be willing to dance with him.”