As Weinstein aftershocks hit Westminster, a watershed for British politics?

Loading...

| London

It started with a Whatsapp group.

The Weinstein scandal had just started to unfurl in the news, and across the British political scene, women began sharing their own stories of sexual harassment on the instant messaging app.

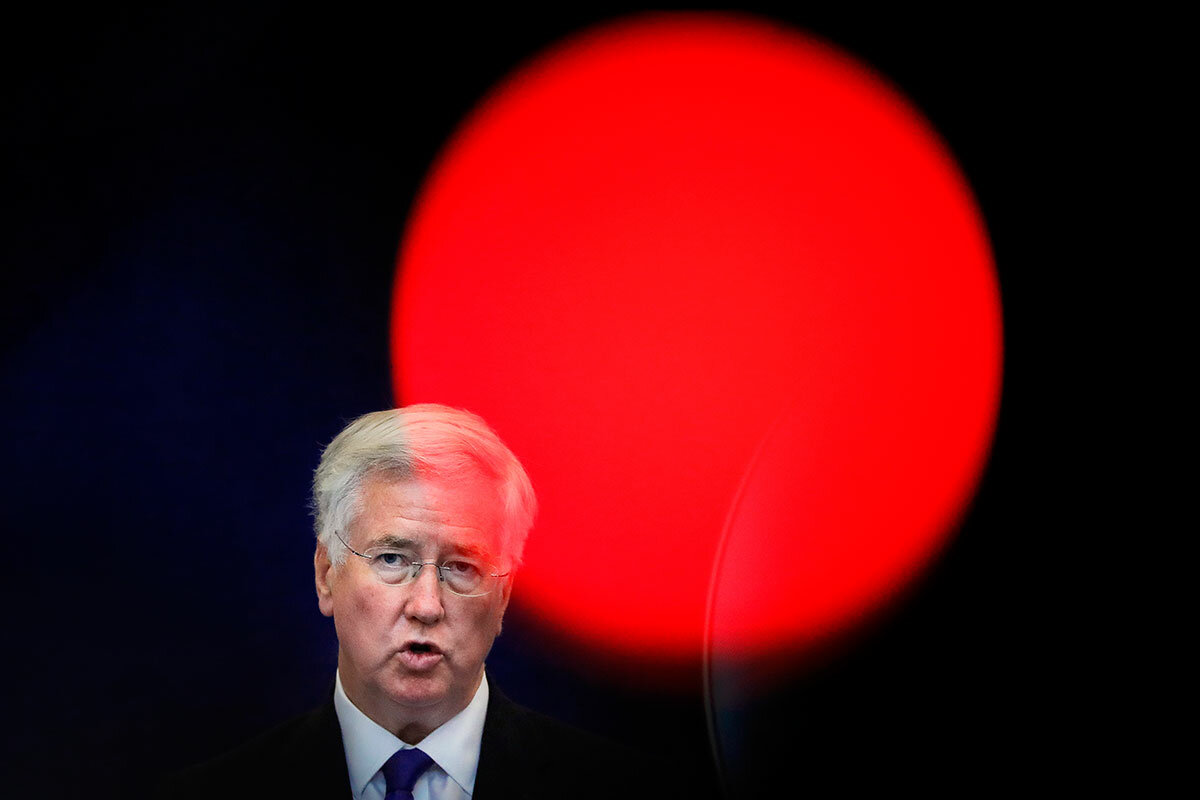

The term “handsy” became the word of choice to describe male members of Parliament with wandering hands, and before long names and alleged offenses – including serious cases of rape and sexual assault – had spread like wildfire around the Palace of Westminster. They soon spilled out in the press and quickly claimed a top-level victim: Prime Minister Theresa May’s right-hand man, Defense Minister Michael Fallon.

Now, with eight MPs from the ruling Conservative party and four more from the opposition Labour party facing sexual misconduct allegations, along with MPs and party officials from most of the other political parties, there is a palpable feeling in Westminster that women from all parties have had enough, says Sam Smethers, chief executive of the Fawcett Society, which campaigns for women’s rights. And they are looking for concrete ways to remake British politics' boys club into something more inclusive.

“Women from all sides of the house are clearly coming together to address it,” she adds. “This is a positive move and will drive change.”

'Radical action' needed

After a series of allegations against Mr. Fallon, including one that he had lunged at a junior newspaper reporter, trying to kiss her on the lips, forced him to resign, Ms. May moved quickly to try to defuse the scandal, holding cross-party talks earlier this week and establishing a new obligatory grievance procedure involving a mediation service.

Many female MPs, though, called the plans disappointing, saying they did not go far enough. And many are now arguing that much more radical action needs to be taken.

Labour party activist Bex Bailey is calling for an independent and impartial body to be set up to deal with allegations. Ms. Bailey waived her right to anonymity recently and told the BBC that she had been raped by someone senior to her in the party six years ago and that she had been warned not to take the matter further if she wanted a career in politics.

Bailey spent three years on the Labour party’s national executive committee trying to make reporting of sexual harassment easier. She pushed through a new, more sensitive complaints procedure for the party, but it is not enough, says Sabrina Huck, a Young Labour activist.

“Young members don’t feel safe reporting senior Labour members in a position of power” because of “fears what it means for their personal prospects,” she says. “Labour is like a family – everyone knows everyone. It does not seem fair to have to expose yourself to people who you are likely to have dealings with again in the future.”

Ms. Huck, like many women, also wants to broaden the conversation about sexual harassment. “This can only be a watershed moment for women in politics if our discourse moves from focusing on individual men to the wider, systemic problems at the root of this scandal,” she argues.

A need for more women?

She is not the only one to call for a sea change at Westminster. Shami Chakrabati, a senior Labour member of the House of Lords, says that while improved procedures are welcome, a “complete cultural change” is needed.

“In Westminster, there is a particular problem, which is that politics is tribal and so you don’t necessarily get the solidarity or honest process that you would get in a normal workplace,” she suggests.

“You get this message that you’d be letting the side down if you complain," she adds. "I think the culture would get better if there were more women. We need to get 50 percent. It’s not good enough until it is, and more women need to be in senior roles.”

Women currently make up 32 percent of MPs – 45 percent within the Labour party but only 21 percent of Conservative MPs. Only a quarter of the journalists accredited to cover Parliament are women.

One way to tackle the hyper-masculine culture might be to implement recommendations in the 2016 Good Parliament report. Among other things, the report proposed making it legally obligatory for political parties to present women candidates in at least half the electoral constituencies they contest.

It also suggested assigning 40 percent of journalistic accreditations to women, and allowing female MPs to breast feed in the debating chamber.

The report, by Sarah Childs, a professor specializing in politics and gender at Bristol University, was commissioned and endorsed by the Speaker of the House of Commons John Bercow.

Outcry, yes. But outrage?

Rainbow Murray, an expert on women in politics at Queen Mary University in London, says the Good Parliament report’s recommendations are more important than ever in light of recent revelations.

“It is an excellent blueprint for where to go next, but the problem is there are a lot of people who have a vested interested in maintaining the status quo,” she says. “Change to empower those that have previously been marginalized never sits well with those who have the power.”

Professor Murray fears that necessary changes will not happen unless the British public expresses significant outrage at the current levels of sexual harassment. “It’s not clear yet whether that’s the case,” she says.

“There’s certainly been a lot of outcry, but it’s also true that there’s a level of ingrained sexism throughout society, with some saying that this is a fuss about nothing,” she adds.

One veteran Conservative MP, Sir Roger Gale, has suggested the scandal is becoming a “witch hunt.” Kathy Gyngell, co-editor of the Conservative Woman website, told a radio interviewer that the scandal demonstrated “a total surrender by Theresa May to the left and the feminists.”

“Not everyone is ready to accept change,” Murray sighs.