In wake of Paris attacks, a new kind of cartoon takes center stage

Loading...

| Paris

As France slowly moves out of a national mourning, just over two weeks since coordinated terrorist attacks killed 130 people in the center of Paris, images, drawings and caricatures have become the city’s unexpected uniting force.

In the 24 hours following the attacks, French artist Jean Jullien’s drawing of the Eiffel Tower as a peace sign went viral, while others penned Paris’s famous oyster-shaped city map dripping with blood or messages of “Paris Rage” and “Peace will prevail.”

Just 10 months after the attacks on satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo brought French cartooning to the limelight and beckoned questions of social acceptability and limits on freedom of expression, the craft is once again forcing the French – especially children – to face tragedy on a collective scale.

Since the attacks, France has seen a rise in press illustrations and cartoons for children, as the government attempts to provide resources for parents and teachers on communicating the events. In the national minute of silence following the attacks, France’s education minister, Najat Vallaud-Belkacem, handed out explanatory materials to parents and encouraged them to use a special hotline for post-traumatic stress.

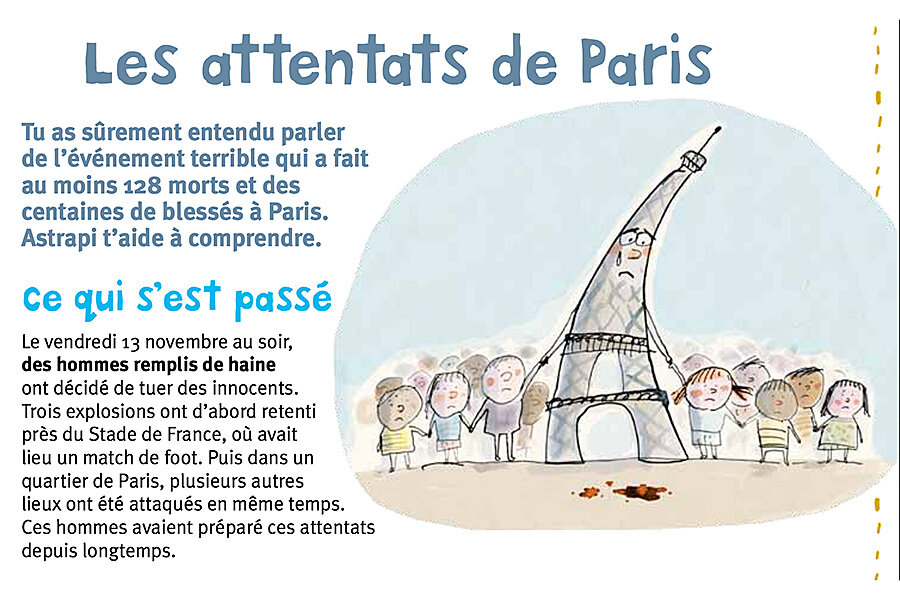

Astrapi, a French children’s magazine, published a free, downloadable tutorial in the 24 hours following the events on how to explain the attacks. The magazine’s illustrator, Frederic Benaglia, says the idea to create a cartoon about the attacks came to him naturally the next morning, after watching the events unfold on TV with his 15-year-old son.

“Drawings go over better than words when it comes to explaining such difficult concepts to children,” says Mr. Benaglia, who put out the two-page resource with his editor and wife, Gwenaelle Boulet. “Children are used to drawing and communicating through that medium, so it was only natural to create these images.”

Benaglia, who has three children under 15, created two principal images – one of a weeping Eiffel Tower joining hands with several children of all nationalities, and another of a group of children pushing back spikes with a large shield marked “Freedom,” to represent the central value under attack in Paris. An accompanying text explains the events in simple terms and how to answer children’s questions.

“For very young children, you’ll want to avoid bringing up the subject,” says Cecile Vienot, a Paris-based child psychologist. “For children ages 5 to 7, you can ask what they know and answer their questions accordingly.”

As children get older, she says, parents and teachers should also be monitoring what they’re viewing on social media and hearing from friends.

“The worst thing you can do is to say, ‘don’t worry,’ ” says Ms. Vienot. “Children can see you’re bothered by what’s happened, so it’s not helpful to tell them not to worry.”

While Benaglia’s and other artists’ cartoons may be helping the nation cope, the images are a step back from the mocking, politically biting caricatures that caused terrorists to attack the staff of Charlie Hebdo last January for its controversial cartoons of the prophet Muhammad. The element of mockery is key to the art of caricature, especially in France, where the craft had its heyday in the 19th century, after government censorship of the practice was finally – although intermittently – lifted.

“Historically in France, caricatures represent a deformation of the body – usually the face – and a politically-charged situation,” says Anne Duprat, a French historian and professor emeritus at the University of Cergy-Pontoise. “They’re usually against people, particularly those in a position of power.”

Cartoons like Benaglia’s, or others that have been published since the attacks – such as the Eiffel Tower consoling a young, high-heeled version of France’s national symbol, Marianne – move away from the satire of traditional caricatures and into the genre of press illustration. But Ms. Duprat says it is in no way indicative of a splitting from tradition.

“We’re far from the end of caricatures,” says Duprat. “We’ve needed unity in our fear and mourning, in this state of war. Cartoons and humor have a way of releasing emotion, to help us deal with all of this and find refuge, especially young people.”

Still, France may be entering a new era of cartooning, as questions of what’s appropriate threatened to sideline satire in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attacks, when the country lost six of its most beloved caricature artists. As French illustrators try to rekindle their mocking zest in the wake of November’s tragedy, they’ll look to their country’s rebellious past for inspiration.

“In France, we’re a little bit anarchist, we like to poke fun and mock, but in the best sense of the word. It’s not violent,” says Benaglia. “Cartoons allow us to think and to realize the power of each individual. We’ll always have this revolutionary spirit.”