A new, unlikely 'nation of immigrants': Germany

Loading...

| Berlin

On a recent day at a bustling Berlin metro stop, a German commuter in a hurry rushed toward a woman to ask for directions. “I don’t speak German,” the foreigner replied in English.

The commuter turned to the next two passengers closest to her on the platform. They shook their heads no. And then she tried the man to her left. He shrugged. “Who speaks German here?” she pleaded. Finally she found a compatriot, and her way, on a busy weekday in Germany’s capital.

It would have been a less likely scenario five years back, and virtually unheard of a generation ago, when Helmut Kohl, the chancellor of Germany from 1982 to 1998, declared that Germany was “not an immigrant country.”

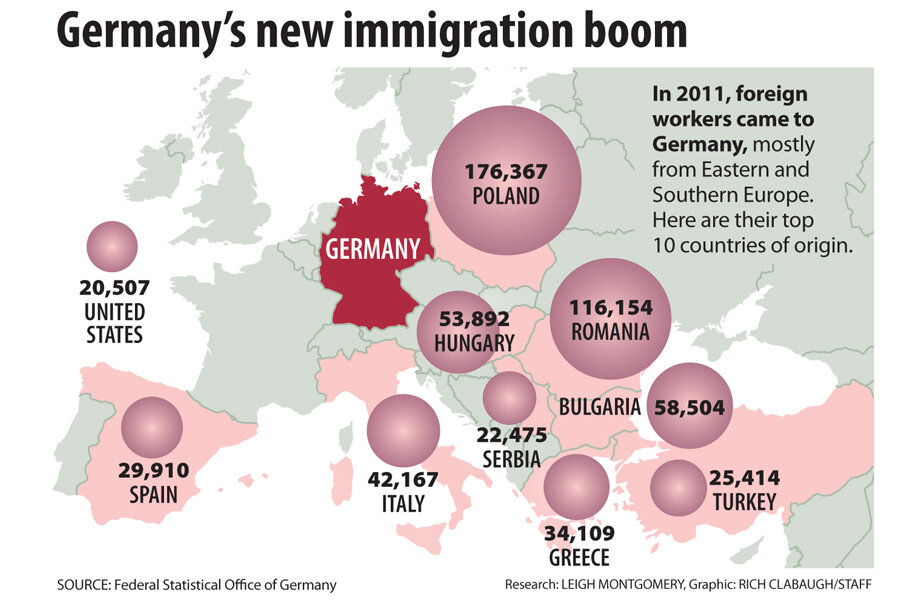

Today, his characterization couldn’t be further from reality. In late spring, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) released figures showing that Germany has surpassed all countries except the United States to become the world’s No. 2 recipient of immigrants, turning this once inward-looking nation into a brewing melting pot. Migrants who once would have headed to London or Toronto are looking at Munich, Frankfurt, and Berlin as the new cities of opportunity.

Leaders in Europe are increasingly talking of closing borders, yet Germany – responding with famed pragmatism as it grows into its role as an economic powerhouse – is quickly opening up. Some economists doubt that the strategy, known hopefully as the “migration miracle,” can keep the economy churning. And very recently there have been some worrying signs of a backlash. But generally, Germany is giving a positive connotation to immigration at a time when populist parties across Europe have turned it into a dirty word.

“I think there is an awareness of the importance of the demographic challenge, and that awareness is fueling the acceptance,” says Thomas Liebig, senior administrator at the OECD’s international migration division. He says the rate of change here has taken even migration experts by surprise.

An immigration nation

Germany is undergoing a sea change from the Kohl era. At that time, Germany was grappling with social problems from earlier waves of migration, notably in the 1960s and ’70s, when Turkish and other “guest workers” arrived to boost Germany’s economy. Many settled but had trouble assimilating.

Strains came again after the Soviet Union collapsed. Ethnic Germans returned in even bigger waves to the country, leading to Mr. Kohl’s famous declaration.

Today, under Chancellor Angela Merkel, Germany strikes the opposite tone. Two-thirds of the country’s new migrants are from the European Union, especially Poland, Italy, and Spain. But Germany is also trying to lure migrants from outside the EU, from India, China, Vietnam, and Indonesia – relaxing its immigration laws so much that it’s gone from having a closed-door policy to having one of the most liberal immigration policies in the world in less than 10 years, particularly the past two.

Its implementation of the EU’s “blue card” system is one of the easiest to utilize, permitting entry to anyone with a university degree and an equivalent-level job offer and salary.

In its most recent figures, the OECD says 400,000 migrants have settled in Germany, a rise of more than 30 percent from the year before. Germany now holds the No. 2 spot for immigration destinations in the world. Just three years prior, Germany sat in eighth place.

Holger Kolb, a researcher at the Expert Council of German Foundations on Integration and Migration, says Germany’s efforts represent a stunning turnaround.

“Germany is a latecomer,” Mr. Kolb says. “Today it’s a major magnet for immigration.”

As befits Germany’s reputation, the change in immigration policy is in large part a pragmatic decision.

The country’s low birthrate and aging population have been looming as issues for decades, but it’s only now, when they’re starting to affect Germany’s economic outlook, that they’ve been the topic du jour in cubicles across the country.

Between 2010 and 2020, the labor force is projected to decline by 4 percent, compared with positive growth in the EU overall (by 2 percent) and the US (by 6 percent), according to the OECD. The areas hardest hit will be the Mittelstand, the small and medium businesses that are the backbone of the German economy, the labor pool in rural Germany, and specific industries like health and elder care.

The ‘first signs of demographic change’

“We are beginning to experience the first signs of demographic change in the labor market,” says Holger Schäfer, a senior economist in the Berlin office of the Cologne Institute for Economic Research.

But the nascent realization of Germany’s demographic woes comes at an opportune time – as youth unemployment rates in Spain and Greece exceed 50 percent, and in Italy are over 40 percent.

Many, like Spaniard Ana Moyano, have found an answer in Germany.

Ms. Moyano, from Spain’s Andalusia region, graduated from a university program in nursing in 2012 in her hometown of Granada. Unlike some of her peers, she didn’t dream of living abroad or learning a new language. But there were no jobs in Spain. The only country that was even posting job advertisements was Germany.

So she responded to an advertisement from an elder care services group here, even though she has only a basic understanding of German. The company interviewed her via Skype and then met her in Madrid. She got the job, which began as a seven-month language and jobs training program that included room and board.

She’s happy for the opportunity to be productive, something she doesn’t think she would have had if she had stayed in Spain. And she says she feels welcome in Germany.

“My German colleagues have helped me a lot,” she says. “They know that if a Spaniard is here, it’s for a job that needs to be filled.”

A note of caution

Still, economists doubt that migration can solve the larger demographic forces at play. Residence Zehlendorf, a nursing home in a leafy suburb of Berlin, demonstrates one reason why.

The home is a calm oasis on a recent day. Birds chirp in the central courtyard. Seniors finish up their lunches in the cafeteria. But Dana Russow, the director of operations, says it’s exactly here that the nation’s demographic storm is forming.

Ms. Russow is responsible for making sure that the 130-plus seniors who live here are cared for by 65 workers. Staffing is no small feat in an industry that pays low salaries despite long hours and draws disproportionately from the baby boom generation that is near retirement – at the same time that the number of people needing elder care is growing.

But Germany’s migration trends have offered few solutions. It’s simply too expensive to recruit abroad, Russow says. Under government rules, her company would have to pay salaries while foreigners take three months of mandatory German language training. They also would have to pay brokers’ fees upfront, which she says equals three months of pay. At the end of the training, the worker is not obligated to stay with them. “You’ve paid six months of work for nothing,” she says.

Instead, she’s trying a new tactic: placing advertisements promising free meals, free public transportation, help finding apartments in Berlin, and a space to bring children to work if they are ill. It has worked so far, but she says she doesn’t know how long that will last.

Russow’s experience is one example of why employers are worried, but there are plenty of others. Some newcomers, such as Moyano, do not intend to settle in Germany. She’s always looking for viable opportunities in Spain so that she can move home. “If I could, I’d return to Spain today,” she says.

And she says she is one of the fortunate ones. Many Spaniards, Italians, and Greeks have found themselves in menial jobs for which they are overqualified. Many have already returned home. Even if they stay, they come from countries that themselves are registering rock-bottom birthrates.

Ferdinand Fichtner, an economist at the German Institute for Economic Research in Berlin, says that Germany has addressed its labor shortage by trying to get more women in the workforce, keeping older people in it longer, and using migrants to fill in the gaps. But what Germany really needs to do is “focus on productivity, through investment in education or infrastructure, to keep Germany competitive despite demographic trends,” he says.

Embracing immigrants

The dominant mood is that migration has enriched Germany, not strapped it. Ms. Merkel has lately been at odds with British Prime Minister David Cameron, who has raised prospects of closing British borders, even to EU citizens who some claim migrate for “welfare tourism.”

Such rhetoric gained a small foot in Germany this year, after all restrictions placed on Bulgaria and Romania expired on Jan. 1. Very recently, marches that are advertised as anti-Islamist, but with with general overtones of intolerance, have gained steam in Dresden. Some Germans are concerned that the pace of refugees flowing into the country, particularly from Syria, is stretching German infrastructure, like housing.

But tellingly, there is no mainstream populist party overtly calling to end immigration as a centerpiece platform, as is the case with the National Front in France or the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) in Britain.

According to this year’s Transatlantic Trends survey at the German Marshall Fund of the US, Germans are more likely to approve of how their government is handling immigration than their European and American counterparts. Two-thirds of Germans say they are not worried about immigration from within the EU. While 54 percent of British respondents say there are “too many” immigrants in their country, only 21 percent say the same in Germany.

Mr. Liebig says the mind-set about migration has evolved as Germany has accepted itself after the scars of World War II. He attributes that to the old adage – “to like others, you have to first like yourself,” he says. “Germany is now accepting itself as a nation.”

And the rest of Europe is accepting it, too. On a recent night in Kreuzberg, a trendy district of Berlin that’s drawn many young Europeans, a group of Spaniards sit outside a local drinks shop. Jorge Garcia, from Madrid, went to London in 2011 but the buzz was all about Berlin, he says. He arrived in January, and the first place he submitted his résumé he got a job, working at an IT support center. “The biggest draw is the city itself, the open mind-set, the way of life,” he says.

Foreign tongues are heard everywhere throughout Berlin: on subway platforms, in cafes, on street corners.

Longtime Berlin resident Gary Smith, who is the executive director of the American Academy in Berlin, moved here before the Berlin Wall fell. He says he was always looking to leave a place considered far more provincial than other cities both in Germany and Europe. “Berlin is now truly cosmopolitan,” he says. “The interest in Germany is at a level I’ve never seen in my lifetime.”