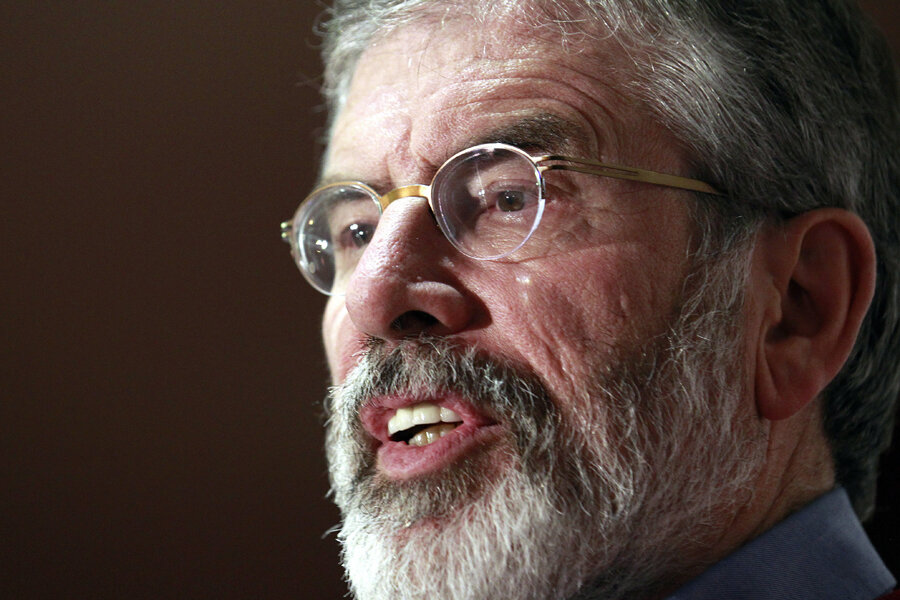

Gerry Adams arrest: Will Northern Ireland peace pay a price?

Loading...

| Dublin, Ireland

The arrest of Gerry Adams, the leader of Irish republican party Sinn Féin, in connection with an unsolved 1972 murder has raised questions about Northern Ireland's peace process, just weeks away from European elections in both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

Mr. Adams has not been charged with any crime and Sinn Féin says he volunteered to meet with police over a month ago. He is being questioned in relation to the abduction and murder of Jean McConville, a Belfast woman accused at the time of spying for the British Army. Her body was found in 2003 and the case remains highly contentious. Police detained another Irish republican, Ivor Bell, in March for questioning in the case. He was later charged as an accessory.

Adams denies any involvement in the killing. In a statement he said: “Well publicised, malicious allegations have been made against me. I reject these.” He also stated that “the killing of Jean McConville and the secret burial of her body was wrong and a grievous injustice to her and her family.” He has long denied being in the Irish Republican Army.

Sinn Féin’s deputy leader, Mary Lou McDonald, claims the arrest is politically motivated, coming shortly before elections in which Sinn Féin is expected to poll well.

A power-sharing peace deal signed in 1998 formally ended Northern Ireland's decades-long conflict between Catholics seeking to reunite with Ireland's south and Protestants who wanted to remain under British rule.

Historical truths and public inquiries

The arrest is thought to follow directly from Boston College's "Belfast Project." In 2012, confidential testimonies by protagonists in the conflict that had been archived by the school were handed over to Northern Ireland's police after a court battle.

Anthony McIntyre, one of the Boston College researchers and a former IRA member, warns that the potential for trouble as a result of the police investigation is real. “Political stability in the North is not as robust as it was five or six years ago. I have long thought the peace process would survive, but it feeds into the instability of it.”

Mr. McIntyre, who has clashed with republicans and does not support Sinn Féin, criticizes the authorities for their priorities in uncovering historical truths and wrongdoing. “It’s a very skewed urge for truth. They’re trying to skewer certain truths," he says.

One example, McIntyre says, is Britain's refusal to call an inquiry into the 1971 killing by British troops of 11 civilians in Belfast, a case in which evidence appears more abundant. He speculates that arresting Sinn Féin leaders like Adams could be a way to pressure republicans to drop their calls for inquiries into abuses by British security forces.

However, Newton Emerson, a commentator on Northern Irish affairs, says claims of political motivation are overstated.

“Will the IRA kick off again if Gerry gets [charged]? That would mean asking if there was any truth in the peace process at all. I don’t see that happening, but people need to think about the politics they’re loading onto a police investigation,” he says.

Popularity over the border

Sinn Féin’s support, and Adams' popularity, has been rising in the Republic of Ireland since the country’s economic crash in 2008. But the allegation that he ordered the killing of Ms. McConville have dogged him for years. His opponents on both sides of the Irish border have repeatedly called for an investigation.

Speaking in April, Gregory Campbell, a lawmaker for the Democratic Unionist Party which shares power in Northern Ireland with Sinn Féin, said police should question Mr. Adams “as a matter of urgency.” And Irish government minister Joan Burton today described the killing of McConville as a "war crime.”

McConville’s son Michael told the BBC he knows who abducted his mother but has not, and will not, tell police as “me, or one of my family members or one of their children would get shot by these people. Everybody thinks this has all gone away. It hasn’t gone away.”

Adams can be held for up to 48 hours without charge under Northern Ireland’s anti-terrorism laws.