As Russian authorities swoop down on NGOs, many wonder who's next

Loading...

| Moscow

Russian authorities have raided hundreds of nongovernmental organizations around the country this week, seizing documents and interrogating staff.

Many activists say the goal of the searches, beyond harassment, is to force the groups to comply with a new law ordering NGOs that receive international funding to self-identify as "foreign agents" – a term they feel makes them sound like spies – or be shut down.

Representatives of the prosecutor's office, sometimes accompanied by members of the tax department and the Federal Security Service (FSB) have targeted as many as 5,000 groups in 83 Russian regions in the ongoing search-and-seize operations, says Pavel Chikov, head of Agora, a Tatarstan-based inter-regional organization that provides legal aid to NGOs.

"We believe this is a preparation for future repressive actions," says Alexander Cherkassov, a board member of Memorial, Russia's largest human rights monitor, whose own offices were searched last week, with some 600 documents seized.

"If organizations refuse to recognize themselves as foreign agents, then huge penalties will be the next step. That will be followed by closing down the organization, and possible actions against the leaders.... But no NGO is going to submit voluntarily to being labeled as a foreign agent," he says.

However, a law passed by the Duma last summer requires every Russian NGO that engages in any form of public outreach that authorities deem political –and that receives any amount of international funding – to use the foreign agent label in all of its public materials and activities.

But authorities are also raiding international organizations that do not fall under the new law, such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, Transparency International, and even two respected think tanks tied to major German political parties – the Konrad Adenauer Foundation and the Friedrich Ebert Foundation.

Some fear the raids on those international groups could be connected with yet another new law, passed last year, which specifically mentioned international organizations and expanded the definition of "high treason" to include any Russian who discloses information the state considers a secret to any "foreign government or international, foreign organization."

'We are not foreign agents'

For their part, most Russian groups have insisted that they will never wear the foreign agent label.

"We will never do it, for one simple reason: We are not foreign agents," says Lyudmilla Alexeyeva, a former Soviet dissident and founder of Russia's oldest human rights group, the Moscow Helsinki Watch Group.

For several months, Russia's Justice Ministry declined to enforce the foreign agent law, and many experts suggested that the ministry's legal professionals were worried about its compatibility with the freedoms guaranteed to citizens under Russia's Constitution.

But in early February, President Vladimir Putin held his annual meeting with heads of the FSB, and urged them to be more diligent in checking up on NGOs.

"No one has the monopoly of speaking on behalf of the entire Russian society, let alone the structures directed and funded from abroad and thus inevitably serving foreign interests," Mr. Putin told his security chiefs, according to The Associated Press.

"Any direct or indirect meddling in our internal affairs, any forms of pressure on Russia, on our allies and partners is inadmissible," he added.

The uptick in raids on NGOs stems directly from this meeting, says Mr. Cherkassov, of Memorial.

"He complained to them that the NGO law was not working. They interpreted that as a direct instruction," he adds.

Excessive checks?

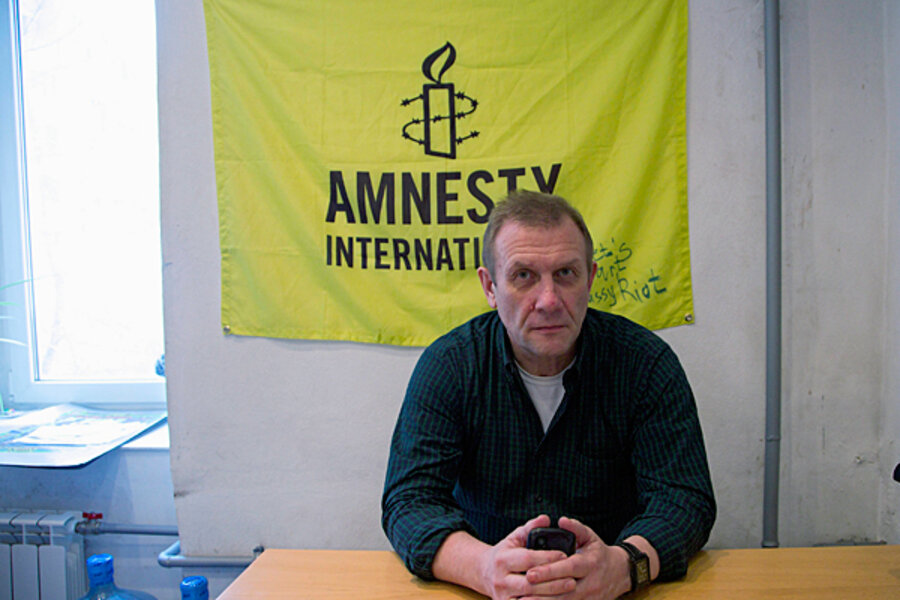

Sergei Nikitin, head of Amnesty International's Russia branch, says his Moscow office was searched for five hours on Monday.

"We were asked to provide a lot of documents that are already on file with the Justice Ministry, including the annual and quarterly reports that we send to the ministry" detailing finances and activities, he says. "I think this is a campaign against civil society in general, and specifically against those groups dealing with human rights."

Indeed, the materials being seized from most of the targeted groups appear to be public documents, mostly the same ones held by the Justice Ministry – which oversees NGOs – says Ramil Akhmegaliyev, head legal analyst for Agora.

"The fact is that NGOs are already under constant and thorough regulation," he says. "They are subject to checks all the time, by almost any government department. Why do this several times, successively? This is not a normal situation."

"It's harassment of current NGOs and a warning to anyone who might be considering getting active," says Mr. Nikitin. "It's also a warning to the whole NGO community to avoid foreign funding, even though it's perfectly legal in Russia.... The way the Russian media is covering these searches, in a completely one-sided manner, gives society the impression that we have something to hide, that we're guilty of something. It creates a totally false impression of what human rights groups do."

Some experts say the campaign against NGOs heralds a wider crackdown in the works, and perhaps show trials to distract Russians from economic and political troubles.

"Our authorities, who are like a collective Putin, feel like they are gradually losing control over the situation," says Dmitry Oreshkin, head of the Mercator Group, an independent Moscow-based media consultancy.

"The economy has stopped growing; people are visibly sick and tired of the same old political faces. So, it's time to launch a search for enemies, consolidate society against the external threat, catch the spies.... Another goal here is to shut down alternative sources of information, and silence the critics who find fault with what the authorities are doing."

"Those groups who uncover corruption, or police abuses, or electoral fraud are going to have their mouths shut. That's what's coming down the road," he says.