When it comes to Facebook, EU defends the 'right to disappear'

Loading...

| Dublin, Ireland

"Leaving Facebook? It was a Kafkaesque nightmare!" says Sean McTiernan, a 20-something Dublin arts journalist, who tried to quit the social network but found that Facebook really didn't want him to leave.

It's rare enough for a young person to ignore the magnetic forces of Facebook, doubly so for someone working in an industry where social media is becoming paramount. But Mr. McTiernan says he was simply exhausted by all the "oversharing" among his online friends. He knew the break wouldn't be easy (and what would become of his social life?), but he forged ahead to pry himself from his virtual community.

"In the end," he says, "I found a program that deleted, one-by-one, every single comment I'd made, every photo I'd uploaded, and every post on my wall."

But even that wasn't enough to convince him that he would vanish. "I revived my profile and left it blank: no pictures, no posts, no friends. It felt safer that way," he says. That way, based on his reasoning, he can make sure he's not on Facebook by maintaining a shadow presence on Facebook.

If the European Union gets its way, people like McTiernan may have an easier time erasing their online selves. The EU wants to give Internet users the right to what the French call le droit à l'oubli – literally, the right to oblivion.

EU in vanguard of Internet privacy

Viviane Reding, the EU's justice commissioner, is pushing for tougher privacy safeguards in an effort to give Internet users more control of their personal data that is collected, stored, mined, and could potentially be sold by companies like Facebook, Google, or any of the vast number of sites where users upload photos, provide private details, and, every once in a while, post something embarrassing.

The new rules, which are set to be in place later this year, put the EU in the vanguard of Internet privacy laws and could influence other countries, namely the United States, as Internet law becomes an increasingly pressing and controversial arena. What's more, the stronger EU stance on privacy may have profound effects on companies like Facebook, which declined to be interviewed for this article, that have millions of users across Europe.

"While social networking sites and photo-sharing services have brought dramatic changes to how we live, new technologies have also prompted new challenges," said Ms. Reding in a February speech. She went on to say it is "now more difficult to detect when our personal data is being collected."

She says "people shall have the right – and not only the possibility – to withdraw their consent to data processing. The burden of proof should be on data controllers – those who process your personal data."

Reding's spokesman, Matthew Newman, says the right to be forgotten is simply a modernization of existing laws: "It already exists in the sense that if you live in the EU you have control over your data. But what's missing is that it hasn't taken account of how we use the Internet now. Fifteen years ago, there was no such thing as social media."

The legal rejig will also see companies forced to prove they need to collect the data for which they ask and allow users to remove all traces of themselves from sites they join.

"If you sign up for Twitter or Facebook or a photo-sharing site," he says, "you agree to share your data, though you probably don't read the terms. It should be very easy for you to delete it, and it should be really deleted."

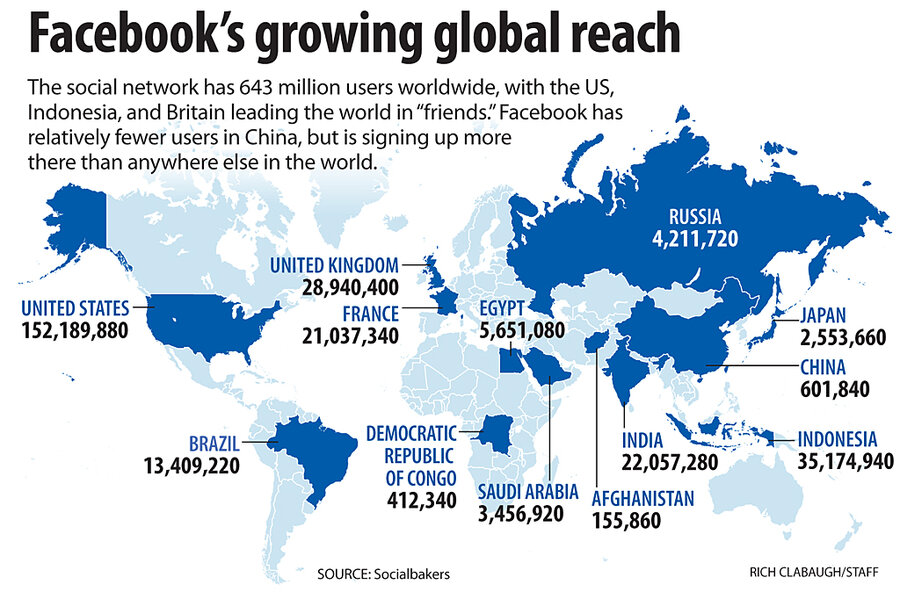

Despite Facebook's 643 million users worldwide, McTiernan is not alone in giving it the cold shoulder. "I refuse to use it ... and am quite happy to work hard at my friendships," says Isabelle De Bretton, who lives in Tunbridge Wells, England, and recently turned her back on Facebook. "I'm known among my peer group as the 'Facebook ranter.'

"When I left Facebook, I found closing the account was a ridiculous experience. You couldn't simply close it down, you had to supply a reason for leaving," she says.

In recent years, Facebook has come under sustained criticism from online privacy advocates with complaints about its deactivating rather than deleting accounts. There is even a Facebook group dedicated to instructing people on how to permanently delete their accounts.

While Europe's move might be welcome in some quarters (especially among those who want to scrub the Internet of their digital footprints), criticism is coming from American technology companies and some advocates who come down on the side of freedom of expression online over the right to privacy.

Writing on his blog, Google's privacy counsel described the move as "foggy thinking" and claimed "privacy is the new black in censorship fashion."

"The concern is largely about young people who are prone to publishing embarrassing photographs that come back to haunt them in later years," says Gavin Phillipson, professor of law at Durham University in England.

While the problem is common across the world, the typical US response is to encourage more personal responsibility and education of users. In Europe, calls to clip the wings of businesses that deal in personal data are a more common response.

'A problem for US in particular'

Lilian Edwards, professor of law at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, Scotland, is a noted civil libertarian in online matters but isn't totally critical of the EU move.

"I initially found it to be a very attractive idea, but subsequently saw some problems with it," she says. "One problem is technical: On the Internet, information tends to get shared around. But from a legal and ethical point of view, the problem is that my privacy is in conflict with your right to freedom of expression. If I write on my blog 'John was drunk last night,' that's personal information about John, but it's also my right to express myself."

Professor Edwards says the EU's attempt to mediate between the conflict of the rights to privacy and expression is "a problem for the US in particular."

"The EU already has a strong privacy regime in the form of data protection [directives] – that isn't so in the US. The move under way in Europe is to strengthen the existing laws. It's not coming out of the blue."

Notably, EU law compels telecommunication companies and Internet service providers to collect data on users for law-enforcement purposes, but the new data protection regime is primarily interested in how businesses use data.

For the justice commission, the issue centers on compliance with European law: "A lot of these services are not based in the EU. But if they are targeting EU customers, they must comply with EU law," says Newman

Edwards adds: "The US, historically and culturally, has been less strong in regulating the private sector – and it's in the private sector in the US where most of this data iskept."