Japan gets coal, gas from historic rival Russia

Loading...

| Moscow

Japan's closest geographical neighbor, Russia, is also the only country with which it never officially made peace after World War II. Until the Japan earthquake hit Friday, relations were at their lowest ebb in decades due to an ongoing territorial dispute over the Kuril Islands, which are within sight of Japan's northern tip.

Yet Russians have responded to Japan's disaster with a surge of goodwill and generosity that, among other things, might just make it easier to resolve that dispute once the current crisis has passed.

As the scope of the tragedy became clearer over the weekend, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev sent three plane loads of humanitarian supplies, including an 80-person earthquake rescue team, and pledged to help make up Japan's energy shortfall by boosting supplies from nearby Russia.

"Our moral duty is to help [Japan] in this situation," Mr. Medvedev said Monday as he ordered Deputy Prime Minister Igor Sechin to look into ways of redirecting up to 6,000 megawatts of electrical power from Russia's far east, and arrange delivery of an additional 200,000 tons of liquified natural gas (LNG) plus unspecified amounts of Siberian coal over the next two months.

Japan is already the biggest buyer of LNG from the vast Russian petroleum field on Sakhalin Island – and the facility's entire annual production has already been sold – but Medvedev instructed Mr. Sechin to ignore contractual limits and find the extra amounts that Japan will need to compensate for the effective loss of two major nuclear power stations in the wake of last Friday's devastating earthquake and tsunami.

"There has been a real outpouring of compassion toward the Japanese people in Russia," says Elgena Molodyakova, head of the official Center for Japanese Studies in Moscow. "A stream of people, including Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, have come to the Japanese embassy in Moscow to lay flowers. Nobody is thinking about politics at a time like this, we are reacting as fellow human beings."

Russia reviewing plans to ramp up nuclear power

Russia, which obtains about 15 percent of its energy needs from nuclear power, had vowed to double that share over the next decade with a major drive to construct new atomic plants, including floating nuclear reactors to meet the needs of remote Arctic and far eastern communities.

But in the first official sign that the Kremlin may be rethinking its enthusiasm for atomic power in the wake of Japan's catastrophe, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin today ordered Russia's Energy Ministry to suspend all building contracts for a month, while a full review is conducted.

The danger of nuclear accidents is a sore topic in the former Soviet Union, where memories are still fresh and large areas are still contaminated with radiation from the 1986 Chernobyl disaster.

The threat was vividly revived during last summer's heatwave, when wildfires raging across central Russia spread to the still uninhabitable Chernobyl zone, leading environmentalists to worry about radiation-laden smoke.

"Because of Chernobyl, Russia has a lot of experience with the problems of radioactive fallout" and its long-term consequences, says Dmitry Babich, an expert with the official RIA-Novosti news agency. "If the Japanese need help in this area, I'm sure Russia will be ready to provide it."

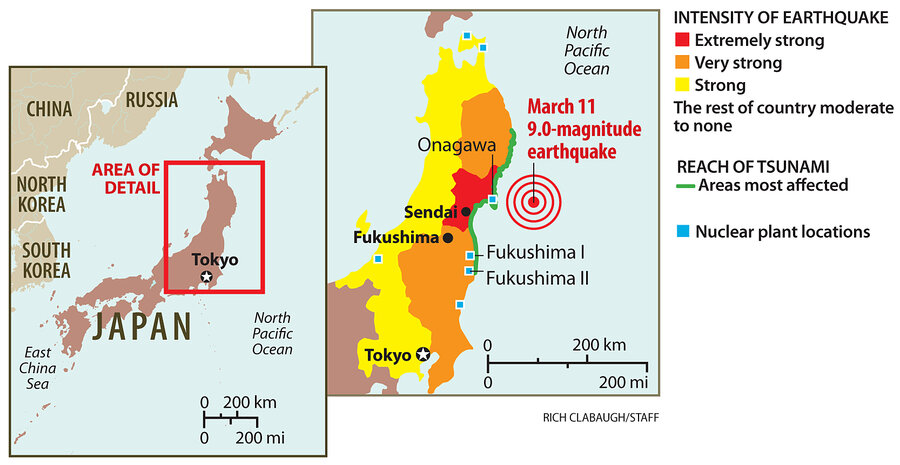

Elevated radiation levels in Russia's far east

Russian media reported slightly elevated radiation levels Tuesday in Vladivostok, which is about 500 miles from the stricken Fukushima nuclear station. But Russian nuclear experts insisted the danger is minimal, and said that winds were expected to continue blowing from Fukushima out into the Pacific Ocean for at least three more days, thus sparing populated areas.

But Russian military officials in Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands, which are closest to Japan, said Tuesday they have prepared contingency plans to evacuate local populations if the situation should grow worse.

Journalists in Russia's far eastern region report that in recent days people have bought up dosimeters, which measure radiation, and emptied pharmacies of iodine pills, which doctors recommend for preventing radiation sickness.

"People are afraid, but calm," says Marina Kononenko, editor of Kamcity, an online newspaper in the far eastern region of Kamchatka. "They are stocking up on face masks, iodine tablets, and geiger counters, and preparing for anything. But authorities aren't offering any advice or instructions, and people fear that even if there is a danger they won't tell us anything."