Pat Robertson Haiti comments: French view theory with disbelief

Loading...

| Paris

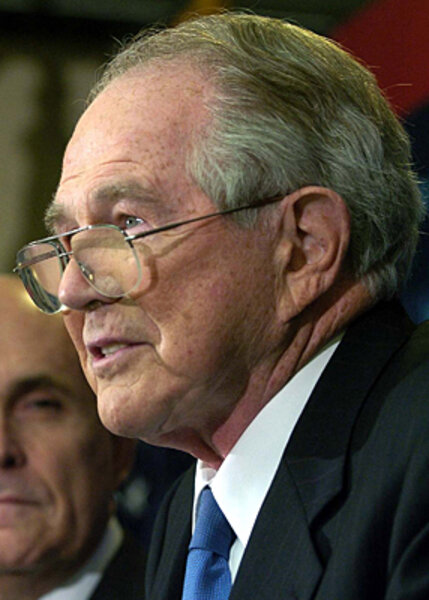

It took about five nanoseconds for evangelical Pat Robertson’s video verdict on the causes of the Haiti earthquake to start making the rounds in France.

Mr. Robertson’s theory that Haitian slaves made a “pact with the devil” 200 years ago in order to free themselves from the hated clutches of Napoleon Bonaparte's regime – resulting in a curse that led to the destruction of much of Port-au-Prince and a massive loss of life in Tuesday's earthquake – got the usual chuckles of disbelief among local intelligentsia about American culture.

It was bad enough that he said the successful slave revolt came during the reign of "Napoleon III, or whatever" (the Haitian Revolution led by Francois-Dominique Toussaint L'ouverture was in fact completed in 1804 when Napoleon Bonaparte ruled France, 44 years before his nephew Napoleon III came to power). But here in Haiti’s former colonial master, talk about the Robertson “theory” clouds with myth an early if awkward chapter in self-determination: the Haitian slaves are considered the first to collectively and successfully overthrow their colonial masters. In this case, the French.

After the French revolution, in 1794, the 500,000 slaves brought from Africa to work Haiti's lucrative sugar and coffee plantations, were freed by decree. But Napoleon Bonaparte, seeking empire, wealth, and territory, tried re-enslave them in 1802.

Once slaves breathed the free air, they did not wish to return to their former status as drones or fodder for empire. Toussaint L'ouverture, a house slave whose father came from Africa, and whose master, Count de Breda, educated him – stepped up. Mr. L'ouverture’s reading of French enlightenment and revolutionary writers Mirabeau and Voltaire is thought to have been extensive. The slave revolt itself took place in the name of the values and ideals of the French revolution in many readings of history here.

Haiti had been “a hell on earth” for the slaves, writes Le Monde’s history specialist, Jerome Gautheret. “Each year, 50,000 slaves were brought to Haiti to compensate for the … terrible mortality among the slaves. In such a fragile society, order could only be precarious, based on terror and violence: the French Revolution shook it in an irreversible way. In Paris, while ‘Friends of the Blacks’ pled for civil equality for all free men and gradual emancipation of the slaves, a powerful colonial party [in Haiti] tried to maintain the status quo.”

Quoted Thursday on Salon.com, UCLA anthropologist Andrew Apter says the notion of a “pact with the devil” as behind the slave victory “is so absurd it is almost funny. This notion of a pact with the devil is basically an echo of an old colonial response to the successes of the 1790s Haitian revolution.”

The problem for Haiti is that if it was a hell on earth under slavery, it was also so after the slave revolt, French historians argue. Africans plucked and sent to Haiti to work under the lash and suddenly freed were not a model constituency for civil society. Haiti went from the largest sugar exporter in the world to chaos. “The plantations were deserted. The former slaves refused to work on the places they were enslaved,” Mr. Apter said.

An emerging understanding of Haiti during this time is of an island increasingly divided between the 30,000 to 40,000 mixed race former slaves, and the more recently arrived slaves from Africa.

UCLA’s Apter argues, “the reason Haiti is poor is because Europe imposed a blockade on trade after the slave revolt in 1804, and you have an extremely polarized class structure in which a few families stepped into the positions of the former colonial plantation owners. There has been a horrible cycle of plundering and autocracy within Haitian leadership.”

Follow the Global News Blog for updates on Haiti throughout the day.