American and German students take cross-ocean class on the Holocaust

Loading...

| New York

On a dreary afternoon in Manhattan's Lower East Side, Ulrike Kollodzeiski walks pensively through the Eldridge Street Synagogue, the first grand house of worship built by Eastern European immigrants more than 100 years ago, back when this area of New York had been one of the most burgeoning Jewish communities in America.

Along with 14 other students from the University of Potsdam in Germany, Ms. Kollodzeiski has come to learn more about Jewish culture and to reflect on the enduring legacy of what she calls the "darkest hour" of her country's history.

She was intrigued by the Moorish architecture of the synagogue a style common for those built in the 19th century and the original ornate Tzedakah alms box, with its seven separate slots for various community causes. The synagogue has been restored in the last decade and now holds a museum as well as the usual weekly Orthodox services. [Editor's note: The original version mischaracterized the synagogue's activities.]

"I really learned nothing about Jewish culture in general at [high school]," says Kollodzeiski, who is now studying history and religion at Potsdam. "I'd taken part in an excursion to Krakau, to the concentration camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau ... [but] Jews seemed to exist only as victims during the time of National Socialism."

Kollodzeiski and her fellow students are participating in an ocean-crossing class developed at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., by history professor Maria Höhn and German professor Silke von der Emde. In March, a group of American students had traveled to Berlin, visiting its synagogues and Holocaust memorials.

While it is billed as simply a multidisciplinary, multicountry course exploring how the Holocaust is variously remembered and memorialized in these countries, the class offers a prism into the different ways Americans and Germans bear the atrocities of the past and how this informs their understanding of conflicts today.

• • •

From each side, they are a select group of students, with interests perhaps not typical of most. But, as many of the German students note, their country has been going through a dizzying cultural upheaval since reunification. In 1990, fewer than 30,000 Jews lived in the combined East and West Germany – a fraction of the number in Manhattan alone.

Today, however, the Jewish presence is once again visible in Germany: nearly 200,000 now reside there, making it again one of the largest Jewish populations in Europe. In addition, Germany, like many other European countries, is grappling with a growing Muslim population, immigrant workers who provide cheap labor but remain, for the most part, culturally isolated and stigmatized by the specter of terrorism.

"Germans are just beginning to see themselves as a multicultural society, but they still see it as ordered – other people who act like them," says Professor Höhn. "And in many ways, as the students explore these questions, America is seen – right or wrong – as the representative of the victims."

Indeed, for many of the German students, two generations removed from the horrors of the mid-20th century, questions of cultural identity and pride often evoke an uneasy ambivalence.

"There is still in Germany a vivid anti-Semitism," says Christoph Kasten, a history student at Potsdam. "It's not on the surface anymore, but it [has become] more subtle, changing its face.... And people are unsure of the meaning of National Socialism and how it affects Germany today. Some are calling the young people to draw a line under Auschwitz, to make up a new German identity without Auschwitz."

While Mr. Kasten strongly disagrees with this trend, he does see it as a crucial question as his country continues to bridge the divide between the West and its former Communist half – as well as the tensions arising from the influx of eastern European and Middle Eastern immigrants.

During the semester, with both groups visiting the other's country and later interacting via videoconference, they've had the opportunity to do research projects together. Kollodzeiski worked with American students studying the impact of a 1978 television miniseries on the Holocaust, while Kasten and his American partner looked at the impact of Daniel Goldhagen's book "Hitler's Willing Executioners" in Germany.

"Americans are very open," says Kollodzeiski. "They ask more questions than we do, because of the education system, I think. We're more, 'What does it mean?,' in an academic way, and it is not as much about ourselves and how we feel about it."

And as many of the German students pointed out, the American students were keenly interested in issues of representation – how television and movies have shaped their understanding of the Holocaust, and whether these images could truly encompass the magnitude of the history.

"A lot of Americans, their understanding of the Holocaust is very much rooted in the media – popular books like [Elie Wiesel's] 'Night,' movies like 'Schindler's List,' the miniseries," says Kegan Andeski, an English and German major at Vassar. "I think that for the German students, they've grown up around it, they've seen the camps. Movies ... are just part of their discussion. It doesn't define it for them like it does with us."

Mr. Andeski is frustrated, too, at what he sees as the Hollywood version of the Holocaust, which he considers distorting. And while he also didn't care for some of the memorials he visited when in Germany in March – some seemed overly dramatic and emotionally manipulative – he was deeply moved by the artifacts on display, like victims' letters to family members. "And Ravensbrueck [concentration camp] was a very powerful place," he says. "On a certain level, it was so powerful because it wasn't powerful at all. At this point, they're just normal buildings, and in that sense it was very frightening."

• • •

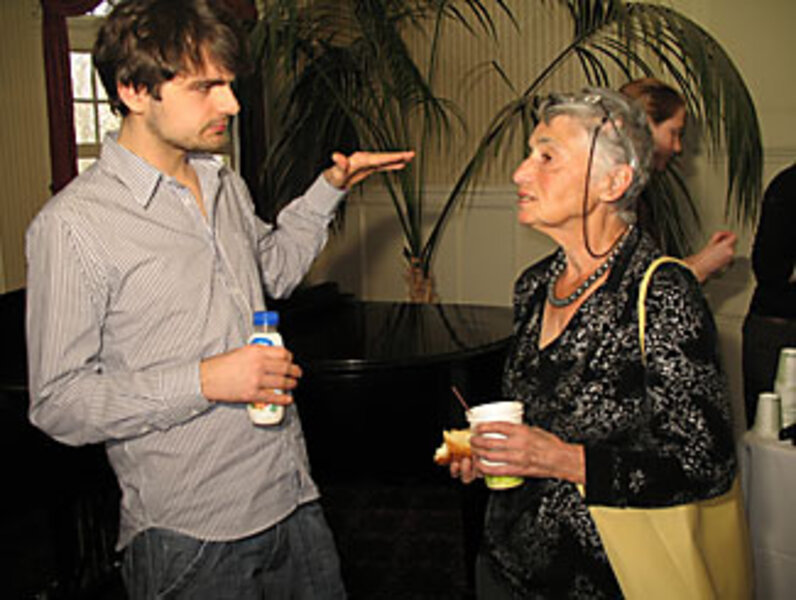

During the week, as students worked together on their projects, they spent time with Ruth Klüger, a survivor and author of "Still Alive: A Holocaust Girlhood Remembered," a controversial bestseller in Germany. A successful literary scholar, tenured at Princeton University and the University of California, Irvine, she engaged the students on issues of censorship, the representation of the Holocaust in art, and German identity.

Her memoir had generated controversy in part because she recalls how female guards were far more humane than male guards in the camps. She recounts her difficult relationship with her mother, who also survived. But her unsentimental and sometimes prickly style surprised some students. When they noted how "Mein Kampf" and the swastika are banned in Germany, she gave a strong defense of the US-style freedom of speech. "I don't believe in outlawing symbols, unless there is a clear and present danger.... And 'Mein Kampf' would never turn anyone into a Nazi," she said.

In some ways, the German students did feel the acute burden of the history they were discussing and its importance to the future of their country. "Everywhere in the world, the cultural distances are so short, and yet so long," says Kollodzeiski. "It is important to respect each other, but how can you respect each other if you don't know each other?"