As Kashmiri crafts struggle, papier-mâché artists find hope in creative evolution

Loading...

| Srinagar, India

Papier-mâché dates back hundreds of years in Kashmir. Local folklore credits the 14th century Sufi saint Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani with bringing the craft to this Himalayan region from Iran, and it flourished under a series of sultans, quickly becoming a symbol of Kashmir’s cultural identity.

But for a long time, the art form was limited to decorative boxes and other items molded from paper pulp.

Not so anymore. These days, the iconic designs popularized by traditional papier-mâché items can be found on bags, leather jackets, and home decor. Artisans apply their intricate designs on unconventional materials like steel, glass, and porcelain, using industrial paints for durability.

Why We Wrote This

In Kashmir, papier-mâché artisans are struggling to overcome the challenges faced by many of the region’s traditional craftspeople – but they also see a reason for hope.

This creative evolution has expanded papier-mâché’s market appeal, with a new generation of clientele emerging – a group that includes interior designers, a local urban bourgeoisie, and international buyers. It could also help Jammu and Kashmir reach its annual handicraft export goal of $344 million by 2029. (The territory currently exports about $140 million worth of crafts per year, according to recent reports.)

It’s a relief – of sorts – to the Kashmiri artisans who have watched similar local crafts die out in recent years. To be sure, papier-mâché artisans continue to struggle with low wages and a lack of new talent entering the craft. Yet Hakim Sameer Hamdani, an architectural historian and design director for the Kashmir section of the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage, says the industry itself is performing better now compared with 20 or 30 years ago.

“As a business, it’s thriving,” he says. “The internet’s role, especially social media and WhatsApp, in design inspiration and market expansion has further driven demand, allowing artisans to reach global buyers directly and removing middlemen.”

In Srinagar city, Jammu and Kashmir’s summer capital, papier-mâché art adorns the walls and ceilings of everything from Sufi shrines and mosques to homes and hotels. It can also be spotted in the windows of boutiques, where tourists and locals alike browse ornate bags or leather jackets. Mohammad Ismail, a retired educationist in Srinagar who collects papier-mâché art, says artists are always innovating.

In papier-mâché, “the main focus is the design,” he says, as he leaves a shop with a newly purchased bag. “It is the color and the pattern, whether it is on a glass or paper, that is authentic.”

Around the world, demand for classic papier-mâché designs – applied to modern products – is growing, says Rahul Dhar, founder of e-commerce platform Treasures of Kashmir. He’s been selling Kashmiri handicrafts since 2020, and in the last few years, interest in papier-mâché jewelry has surged on his platform.

“Earrings, bangles, necklaces, are some items that are in heavy demand on our platform,” he says, adding that many of the clients he interacts with are “youngsters.”

For artists, customer enthusiasm doesn’t always translate into prosperity.

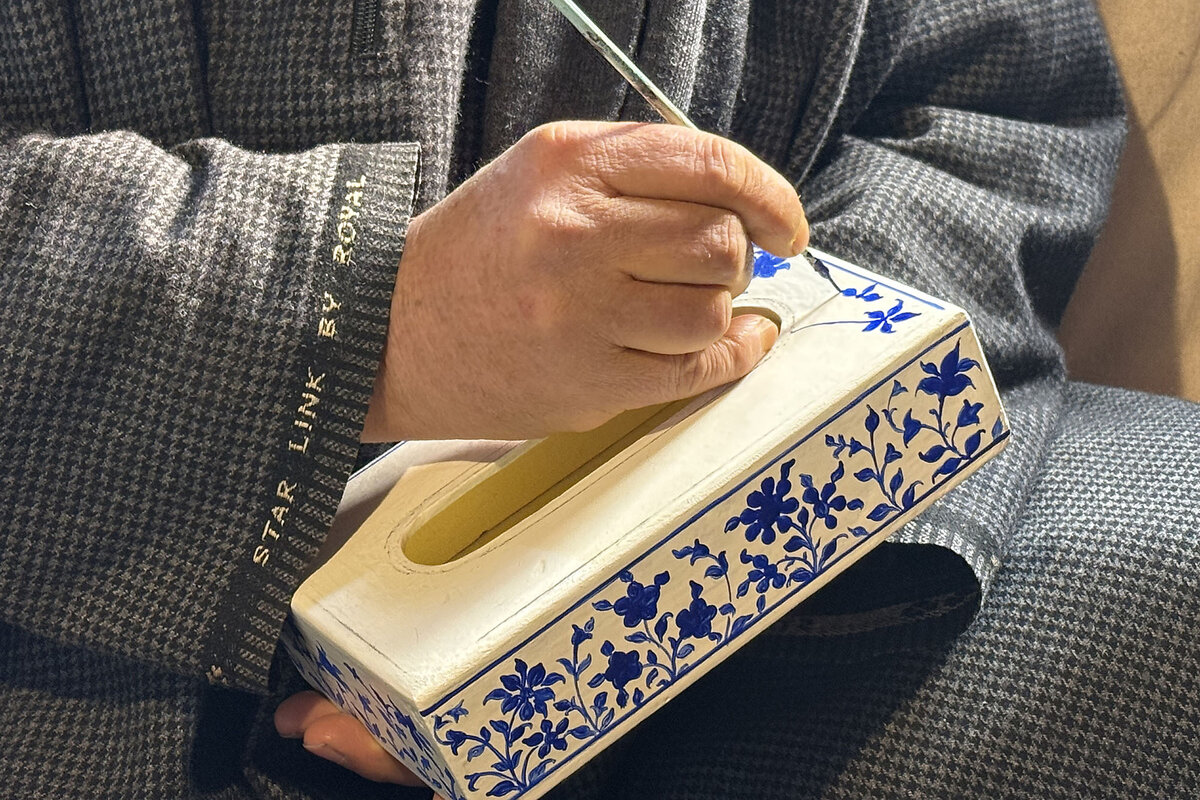

From his home in a historic neighborhood of Srinagar, Syed Maqbool Rizvi paints intricate floral patterns on a decorative box. His day started at 9 a.m. and will end at midnight. Despite having a loyal customer base that he communicates with via WhatsApp, he only earns the equivalent of about $5 for an entire day’s labor.

In Kashmir, the average day laborer earns $8.

The award-winning, seventh-generation papier-mâché artisan will be the last in his family to master the craft. His children – a son and a daughter – have chosen different paths.

“There were many families known for this craft, but their children have moved on,” Mr. Rizvi says. “Everyone looks for private jobs these days – who can afford to sit from morning till night for this kind of work?”

Government loans during the pandemic helped, he says, but it’s become almost impossible to make ends meet through papier-mâché alone.

Historian Bashir Ahmad Maliyar, whose doctoral thesis examined the evolution of Kashmir’s Mughal-era arts, crafts, and trade, says it will take more aggressive interventions to reverse the decline in active artisans.

Without policies that ensure fair wages, incentivize arts education, and promote the region’s crafts, “papier-mâché will vanish within 10 to 20 years,” he says. “People may still practice it in isolated ways, but once the art dies, reviving it will be difficult.”