How wrestling became a battleground for women’s safety in India

Loading...

| New Delhi

For weeks, some of India’s top wrestlers – including two Olympic medalists and an Asia Games champion – have been living out of a yellow tarp tent on a sidewalk in Delhi. Their goal? To topple the most powerful man in their sport: Brij Bhushan Sharan Singh.

The president of the Wrestling Federation of India (WFI) has been accused of sexual harassment by seven women wrestlers, and protestors say the government has failed to take action against him.

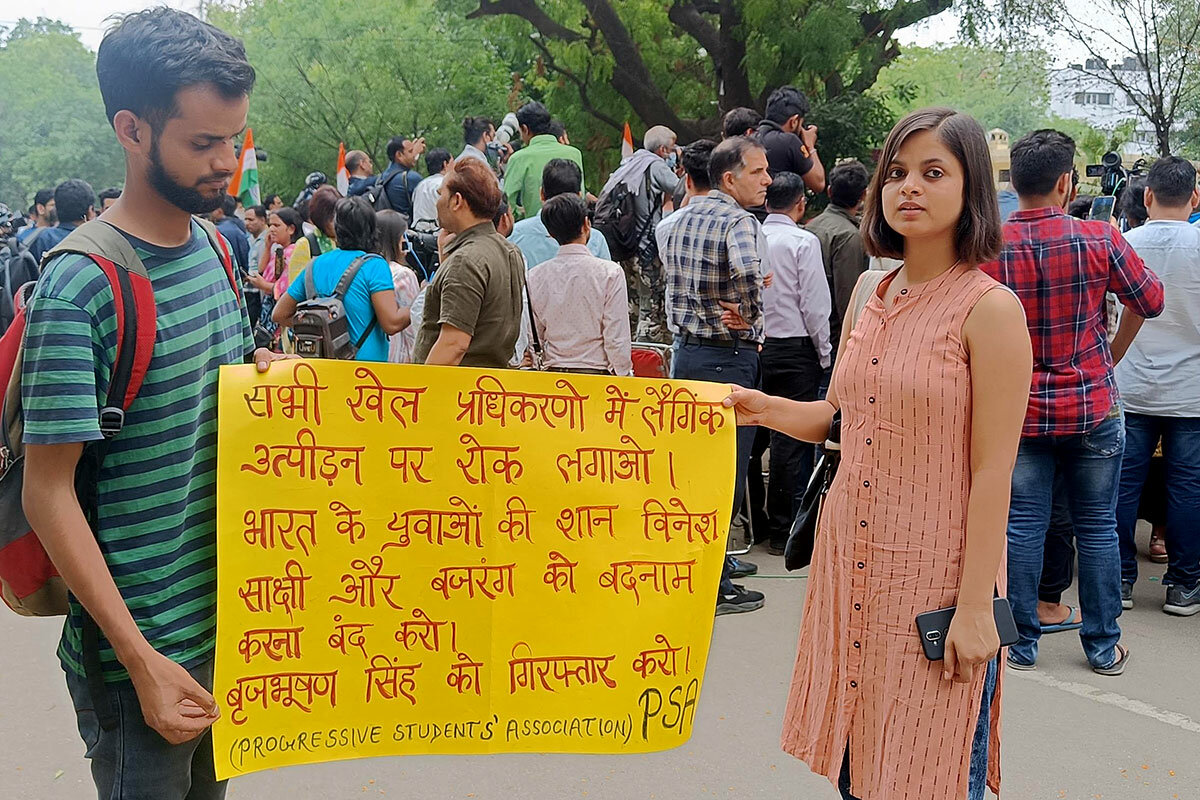

Out on the street, the wrestlers have company. One hot morning last week, dozens of farmers joined the protest, squeezing past security forces in blue fatigues and police barricades. Wrestlers’ families and friends are there, too, and politicians from opposing parties have spoken out in support of the athletes.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onThe USA Gymnastics sex abuse scandal showed how cooperation and courage can lead to safer sports for young women. Now, Indian wrestling is having its own #MeToo reckoning, capturing the nation’s attention and inspiring a rare show of solidarity.

It marks India’s largest demonstration for women’s safety in over a decade, and the largest ever in the world of Indian sports. Organizers have promised to scale up the protests if Mr. Singh is not arrested by May 21. But no matter how the weekend plays out, the sit-in has already succeeded in raising awareness about the challenges India’s female athletes face.

The demonstration has “caught the attention of the nation,” says Indu Agnihotri, former director of the Centre for Women’s Development Studies in New Delhi. “It’s sort of forcing people to sit up and acknowledge that [sexual harassment] happens.”

In complaints recently filed to police, wrestlers cite several instances of abuse dating from 2012 to 2022. Mr. Singh, who is also a member of parliament from India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, has vehemently denied any wrongdoing.

“All allegations are fake,” Vinod Tomar, former assistant secretary of the WFI, told the Monitor in a text message. The Monitor reached out to the Sports Authority of India and the WFI for comment but has not received a response.

Returning to the street

The wrestlers first staged a sit-in in January but called it off days later after sports minister Anurag Thakur promised a fair and thorough investigation. The government did form an oversight committee to look into the allegations and asked Mr. Singh to temporarily step aside. But the committee’s report, submitted in early April, has not been made public, and critics say Mr. Singh has not faced any repercussions.

So three months later, the wrestlers returned.

“It is unfortunate that we are having to protest for the dignity of our sisters and daughters,” says Bajrang Punia, an Olympic wrestler and one of the main protesters, noting that police did not register a formal complaint against Mr. Singh until late last month, when the wrestlers petitioned the Supreme Court of India to intervene. “This shows how powerful he is.”

Last week, the Indian Olympic Association announced that it would be taking over WFI operations, and Mr. Thakur urged the wrestlers to end their protest, saying that “they must have faith in our law and order.”

The wrestlers aren’t taking his word this time, vowing to stay until Mr. Singh is behind bars. They’ve made the protest site their home, sleeping on thin mattresses under mosquito nets and doing their morning calisthenics on the street. A noisy air cooler provides some respite from the Delhi summer as kids – relatives of one of the wrestlers – take selfies inside the tent.

A landmark moment

India’s last public reckoning on women’s safety was in 2018, when scores of women came out with accounts of sexual harassment by high-profile men, including a government minister. But the wrestlers’ protest is more significant, says Professor Agnihotri.

“The #MeToo movement put the issue of sexual harassment in a very visible manner on the public agenda, but #MeToo did not spill out on the streets,” she says, noting how the outrage was mostly limited to social media and to a relatively urban, elite section of Indian society. The protesting wrestlers come from Haryana, a rural state in northern India “which has not been known for being very gender sensitive in its public assertions,” says Professor Agnihotri.

She views the protests as a “marked shift to the positive” in terms of how Indians view sex crimes. Families generally discourage women from talking about rape and sexual harassment because of the social stigma, but the wrestlers’ families have been remarkably supportive. On the day the Monitor visited, the mother-in-law of Sakshi Malik, one of the original protesters and also India’s first female wrestler to win a medal at the Olympics, was standing by the athlete’s side.

The protest has also received support from khap panchayats – village councils often seen as conservative – and farmers unions.

Among supporters, there is anger at the government, including Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who has yet to comment on the protest.

“I want to ask the prime minister, why are you silent?” says Sudesh Goyat, a veterans’ rights activist. “When these wrestlers win medals overseas, you call them India’s pride, you pose for selfies with them. So why are you silent now?”

Nigam, a college student who goes by one name, says the way police and sports authorities have treated the wrestlers should be a red flag for all Indian women.

“These people sitting here are not ordinary individuals; they are well-known figures,” says Nigam. “If their voices aren’t being heard, can you imagine what will happen if a common woman raises her voice? Nobody will take a stand for her.”

Setback for women in sports?

The protest presents especially high stakes for India’s burgeoning wave of female athletes.

Wrestlers and allies are hopeful that these unified demonstrations will lead to justice and help change a system that leaves young female athletes particularly vulnerable to abuse. They’ve seen it happen before in the United States, with the Larry Nassar case.

But some athletes worry that if the protests fail or become too politicized, this could have a chilling effect on women’s participation in sports, which has only recently started to improve.

Jagmati Sangwan, vice president of the All India Democratic Women’s Association and a former international-level volleyball player, says that the allegations and the authorities’ lackluster response could “crush” budding athletes’ motivation.

She recalls how in the 1980s and ’90s, families wouldn’t enroll girls in sport out of concern for their physical safety. Girls were also discouraged out of fear of social stigma that becoming an athlete would make it harder to find a husband or bear children. Even when 27-year-old sprinter Dutee Chand was starting out, sportswomen still faced immense challenges.

“There was no infrastructure, no coaches, no supplements for female athletes,” she says, adding that things have improved since. “The Sports Authority of India has training centers all over the country, and the government has come up with several schemes to encourage female athletes.”

At the Rio de Janeiro Olympics in 2016, all of India’s medals were won by women, which inspired a lot of girls to enter sports. But just because girls are more accepted on playing fields, doesn’t mean they’re always safe there. Indeed, experts say that these wrestlers’ accounts are almost certainly the tip of the iceberg. “What lies behind them, all that will be just absolutely silenced if these women fail,” says Professor Agnihotri.

While Ms. Chand says only the courts can determine Mr. Singh’s guilt, she admires the wrestlers’ grit. “A lot of people don’t raise their voice out of fear,” she says. “These wrestlers have shown great courage in coming forward.”