India’s street kids rarely make headlines – so they write their own

Loading...

| New Delhi

In just three years, Kishan Rathore went from selling snacks and cigarettes outside a liquor store to running monthly editorial meetings and coaching cub reporters on spotting and gathering news. The catch? These reporters are 12 years old, and their editor, Mr. Rathore, is 17.

They write for the only newspaper by and about India’s street-connected children – a difficult-to-define but extremely vulnerable population of youth who rely on the street for livelihood and/or shelter, and are often inadequately supervised by adults. There is no official data on street children in India, but estimates put the figure as high as 18 million, the most of any nation in the world.

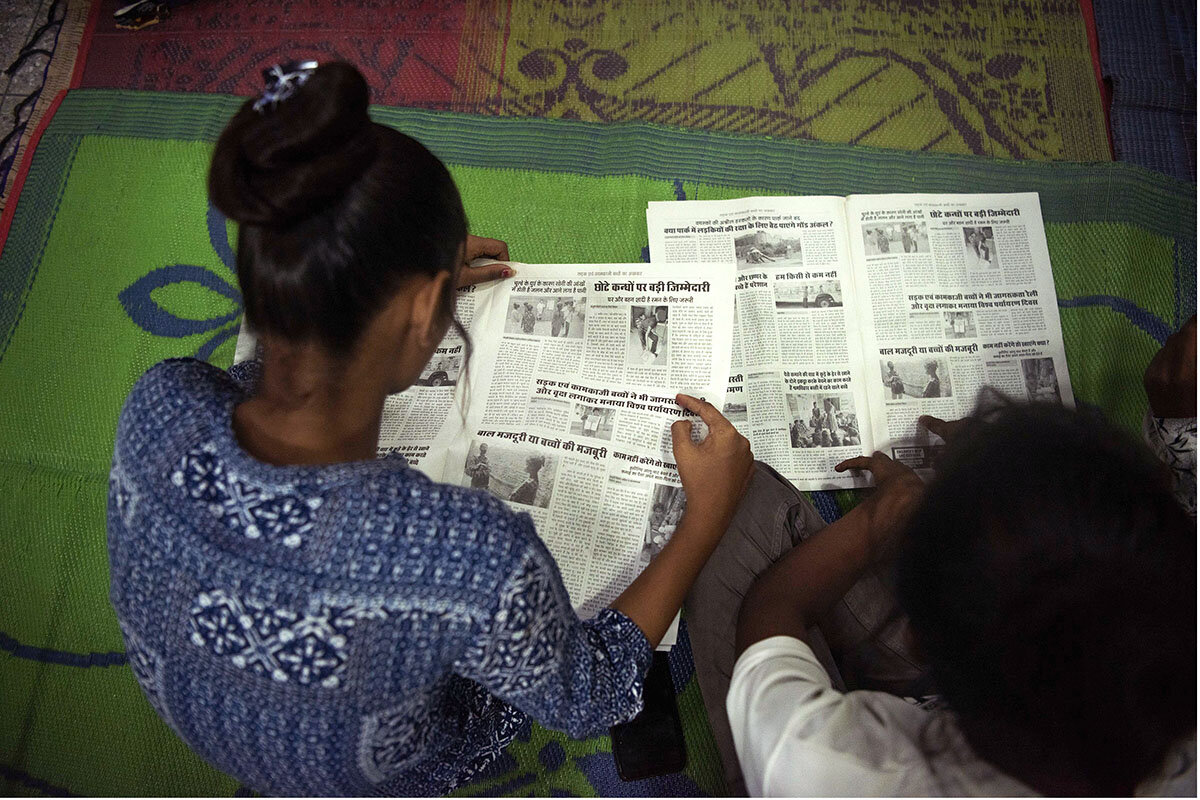

Balaknama, meaning “the voice of children,” is a monthly tabloid published both in Hindi and English by Chetna, a nongovernmental organization that works for the rehabilitation of street-connected children. The eight-page paper features around 40 stories on issues affecting street kids across northern India, and since its first issue in 2003, readership has grown to over 10,000, according to Chetna founder Sanjay Gupta.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onIn India, a newspaper by and about street children offers a rare look into a community often described as “invisible.” Its success shows change is possible when vulnerable groups have the opportunity to tell their own stories.

Former staff members say that Balaknama not only set them up for success personally, but also helped improve conditions for street children throughout the region via their reporting. For caring adults, the paper offers a unique opportunity to understand the issues that matter to youth on the street, a group that’s often described as “invisible.”

“Rarely do we get to hear children talking about their own stories, about their choices, concerns, quests, and even confusions,” says Soha Moitra, a child rights activist and the director of development support at Child Rights and You. “Whenever we hear them, mostly it is through adults’ viewpoints. It is we the adults who usually portray them as we see them through our own lenses.”

She believes Balaknama exemplifies the growth that can happen when we encourage and empower children to speak freely. “What a huge cathartic feeling it actually provides them with, when they are able to express their stories in their own language and give vent to their pent-up emotions,” Ms. Moitra says.

Becoming a Balaknama reporter

The paper currently has an editor, Mr. Rathore, and four reporters. There are also over 35 batuni (“chatty”) reporters – children who provide leads for the stories but can’t write themselves – working for the tabloid in at least three areas including New Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh.

Mr. Gupta, Chetna director and Balaknama mentor, says the idea for Balaknama hit him during a community meeting with street children in 2003. “Those days, the newspapers were publishing reports about the missing dog of an Indian celebrity. A child in the meeting stood up and said that a dog had made it to the headlines, but not the street children who go missing,” he says.

Balaknama seeks to change that by handing the reporter’s notebook to the kids.

The children’s journey typically starts with education intervention by Chetna; then come the weekly support group meetings where kids are encouraged to talk about the challenges they’re facing. For Shambhu, a former Balaknama editor who goes by one name, this was his on-ramp to journalism.

Shambhu was 8 years old when he and his father moved from Bihar state to New Delhi, where the duo spent their days selling cucumbers from a handcart at the Nizamuddin railway station. Chetna activists convinced Shambhu’s father to allow his son to attend classes for a half-hour each day, and later, at a weekly support meeting, Shambhu mentioned how a police officer would beat him and other children working at the station.

“The news was published in Balaknama, and I felt really good that something I had said was printed,” he says, adding that the police officer never beat him or any other child at the station again.

Shambhu was promoted to reporter after working as a batuni reporter for two years, and he eventually took over as editor of Balaknama, a position in which he repeatedly witnessed the power of street kids’ testimony.

In a 2016 issue, Balaknama reporters wrote about how police would ask street children to pick up abandoned dead bodies from the railway tracks in Agra, a city in Uttar Pradesh. “After the story was printed in Balaknama, it reached NCPCR [National Commission for Protection of Child Rights, a government-run body] and they issued a notice and asked to put a stop on this practice,” says Shambhu, who is now 22 years old.

He says that authorities also responded to another story out of Agra about a government-run school feeding children spoiled milk, and that many national newspapers have followed up on the articles as well.

After his affiliation with the paper, Shambhu finished his schooling and got a job at a private school where he teaches children from underprivileged families. He is currently pursuing a bachelor’s degree.

Hitting the streets

Jyoti, another former editor of Balaknama, has also had a dramatic life trajectory. Now 22, Jyoti spent most of her childhood living under overpasses in Delhi, begging at traffic lights and sifting through garbage for valuables in an effort to support her family.

She made $2 to $3 a day begging and ragpicking, sometimes for 18 hours straight. During this period, Jyoti, like other kids in her community, struggled with drug addiction and sexual harassment.

An activist from Chetna reached out to Jyoti, and after weeks of persistence, she agreed to attend open classes. “There I underwent counseling for de-addiction and began learning how to read and write. My habits changed and I began to lead a hygienic life,” she says.

Jyoti joined Balaknama in 2008 and got a stipend, which allowed her to quit begging and ragpicking. “My life came on track and I could support my family financially. I attended school and now I am in 10th grade,” she says.

Jyoti still contributes to Balaknama as a guest writer while working as a mobilizer for Chetna.

Reflecting back on her Balaknama career, Jyoti says her dogged reporting brings her pride. Jyoti recalls writing in 2015 about how children as young as 9 years old would sell alcohol and drugs in the slums of Delhi. “I visited one such slum and investigated the matter. I came to know how a contractor would hire these kids to sell drugs and alcohol. I published the story and distributed the tabloid in the slum also. Soon after, the contractor stopped hiring the kids,” she says.

Jyoti says she has been instrumental in stopping several child marriages, too.

“I have become a seasoned reporter. Unlike those working in fancy studios, I can report in the harshest conditions,” Jyoti says with a laugh.