Looking beyond the Ghandis, Indian party rebukes dynastic politics

Loading...

| New Delhi

India’s main opposition party Indian National Congress is set to choose a non-family member as its next president as it struggles to recover before key upcoming elections.

While it’s historically been led by the powerful Nehru-Gandhi family, Sonia Gandhi and her son Rahul Gandhi decided to bring in a new face during a challenging time for the party, which has been beset with crushing defeats in national and state elections since Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist party came to power in 2014.

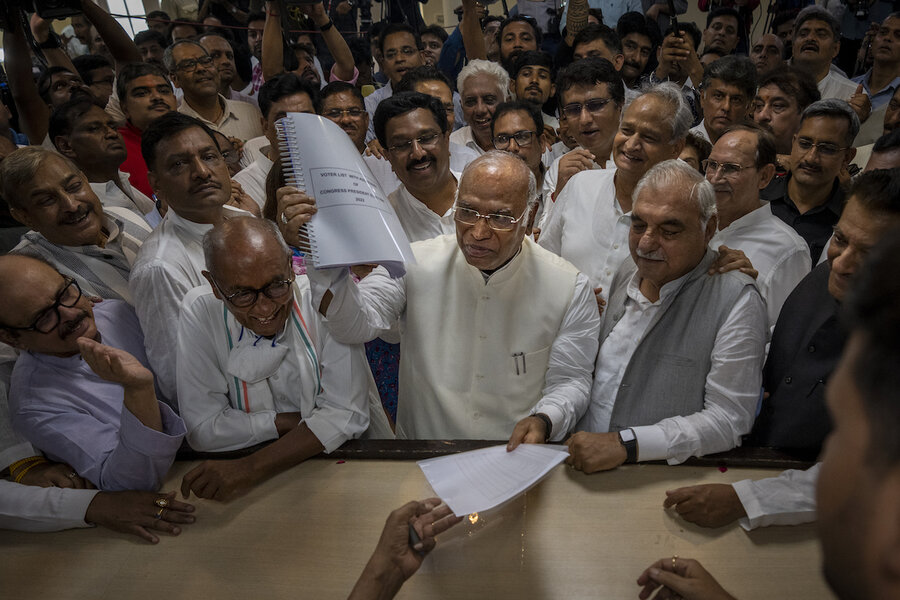

Their choice fell on a trusted party leader: Mallikarjun Kharge from southern Karnataka state.

Mr. Kharge, a member of Parliament and a former Railways, Labour, and Employment minister, filed his nomination Friday at the party headquarters in New Delhi. He will be challenged by Shashi Tharoor who spent nearly 30 years rising in rank at the United Nations before joining the Congress party in 2009.

If both Mr. Kharge and Mr. Tharoor stay in the race after the Oct. 8 deadline to withdraw nominations, 9,000 party delegates will vote on Oct. 17 and the result will be announced Oct. 19.

The filing of nominations is a major step toward ending the party’s struggle to find a successor after dismal results in the 2019 national elections and Mr. Gandhi’s subsequent resignation.

“I tried to convince Rahul Gandhi to accept the party members’ wish to assume the post of president, but he is sticking to his stand that no one from the Gandhi family will be in the race this time,” said Ashok Gehlot, top party leader.

Mr. Gandhi’s family has produced three of India’s 15 prime ministers since independence, starting with his great-grandfather Jawaharlal Nehru who served as the country’s first. Two of them – his grandmother Indira Gandhi and father Rajiv Gandhi – were assassinated. The party ruled India for more than 60 years after India gained independence from British colonialists in 1947.

Mr. Modi, the current prime minister, has denounced Congress’ dynastic politics. The party has been led by non-family members in the past, but Sonia and Rahul have been at the helm of party affairs since 1998.

“The party president is a key post, but never more than now after two general election losses and a vote base at 18% – half that of the ruling Hindu nationalist party,” said Mahesh Rangarajan, a professor of History and Environmental Studies at Ashoka University. “Yet this is the single largest opposition party by far with a history of comebacks as in 1980, 1991, and 2004.”

“The focus is on who, but the crisis is as much of ideas. It is about how to combine bread-butter politics with facing up to the new nationalism of the ruling party,” Ms. Rangarajan said.

Critics describe key leaders leaving the Congress party – including veteran Ghulam Nabi Azad, who announced his own political party in September – as a revolt against the Nehru-Gandhi family’s domination.

In his resignation letter to Sonia, who has been serving as interim party president, Mr. Azad said that “the entire consultative mechanism was demolished by Rahul Gandhi when he took over as Congress vice president in 2013.”

He lamented that “all senior and experienced leaders were sidelined, and a new coterie of inexperienced sycophants started running the affairs of the party.”

Mr. Gandhi is on a 3,500-kilometer (2,185-mile) walking tour of Indian cities, towns, and villages over the next five months as he attempts to rejuvenate the party and win the people’s support ahead of two key state legislature elections in Himachal Pradesh state and Mr. Modi’s home state of Gujarat. The results are likely to impact the country’s next national elections due in 2024.

This story was reported by The Associated Press.