New Delhi gang rape verdict: 'death to all'

Loading...

| New Delhi

A New Delhi court today sentenced the four men convicted of gang raping and murdering a 23-year-old medical student, pronouncing “death to all" in a ruling that underscored the outrage caused by the case.

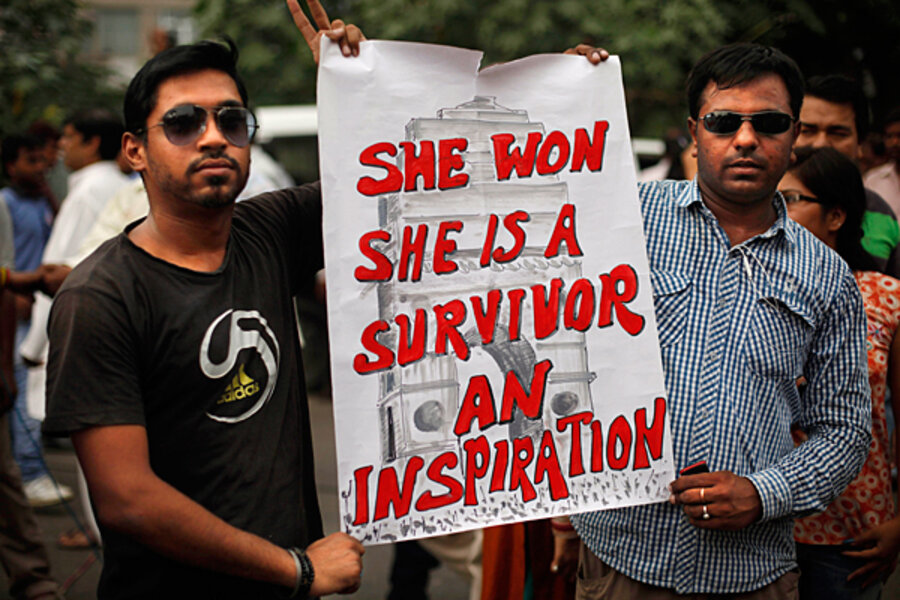

The attack last December sparked large protests across India as demonstrators and activists called for reform of sexual violence laws and demanded changes in attitudes toward women. The death penalty in India is reserved for only the “rarest of rare” cases.

“This [case] falls under inhuman nature of the convicts and the gravity of offense they committed cannot be tolerated,” said Judge Yogesh Khanna in his ruling. “[The] court cannot turn a blind eye to such a gruesome act. When crime against women is rising on day-to-day basis … at this point in time [the] court cannot keep its eye shut. … The case falls under the rarest of rare category.”

A total of six men were accused of tricking the physiotherapy student and a male friend on their way home from a movie onto a chartered bus on Dec.16. Prosecutors said the men beat her male friend and raped the woman, using a metal bar to inflict serious injuries. The two were then dumped, naked, by the side of the road. The woman later died of her injuries in a Singapore hospital.

The driver of the bus where the attack took place committed suicide in jail earlier this year, and a juvenile court found a 16-year-old guilty last month, sentencing him to three years in a reform facility.

As three of the four of the sentenced men broke down in tears after the ruling was issued, defense lawyer A.P. Singh told reporters the punishment was motivated by public anger and political pressure, not justice. He said he planned to appeal the ruling.

Though the country sentences about 130 people to death every year, India has only executed three people in the past 17 years, due largely to the slow bureaucracy of the judiciary and the Indian government's reluctance to carry out the death sentence. Two of the three executions have come in the past year for terrorism convictions.

Just a step

Kavita Krishnan, of the All India Progressive Women's Association, which has been at the forefront of the protests, said that the death sentence was only a step toward addressing India's rape culture. Justice seems to have become rare in India, she argues: “it applies only to a case where there is public outrage.”

She also notes that 20 out of 23 recent rape cases have resulted in acquittal in the same Delhi courthouse. The reason, she says, is that police focus too much on forensic evidence, which is not always available, and often assumes female victims are lying.

“The process of prosecution needs to be improved so that every rapist knows he is not going to go scot-free,” she says.

According to government statistics, 244,270 crimes against women were reported in India in 2012, though women's rights groups say those numbers are under-reported. The trend in Delhi suggests that 2013 may see a sharp increase. Delhi recorded 706 rape cases in 2012; by contrast, in the eight months ending Aug. 31, 1,121 rape cases have been registered. The number of sexual harassment cases in the national capital has risen from 381 reports last year to 2,267 this year.

Positive change?

Women's rights group and Delhi police say the increase in rape cases is a reflection of more women seeking justice rather than keeping silent because of social stigma associated with rape. It also appears that police, who have been known to turn away complainants, have started to take accusations more seriously.

"Today, complaints are recorded verbatim and (registered cases) are filed simply on the basis of the women's complaint without raising any issue," an unnamed police official was quoted as saying in the Times of India newspaper.

There are other indicators of positive change since the December attacked garnered so much attention in India and across the world.

“The biggest change is in social awareness. Everyone is talking about and questioning the rape culture,” says Mumbai-based women's rights lawyer Flavia Agnes. “The police, courts, media and everyone is taking rape with a new seriousness. Newspapers love to say that nothing has changed, but those who have been working on violence against women closely can't agree. There are special courts and judges and most cases get disposed in a year."

Courts have become stricter in giving bail to those accused of rape, and judges even refer to the Dec. 16 protests in court proceedings, lawyers say.

“You can even see the change in court infrastructure, which makes sure that rape victims don't have to see the perpetrator eye-to-eye in the courtroom,” says Delhi-based lawyer Rohit Kaliyar.

“There is special effort that the rape victim should not feel further victimized by the trial process, as used to be the case,” he says.